Suzanna Ogunjami

Murrell, Denise (ed.), The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, exh. cat., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, edited by Denise Murrell, Yale University Press, New Heaven & London, 2024

→Ottenberg, Simon, Conflicting Interpretations in the Biography of a Modern Artist of African Descent, Journal of West African History, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Fall 2015), pp. 45–70

→Negro Artists, exh. cat., Harmon Foundation at the Art Center, New York, foreword by Alain Locke, 1933, 55 p. Digital version from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States, 25 February–28 July 2024

→African Modernism in America, 1947-67, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., United States, 7 October 2023–7 January 2024

→To Conserve a Legacy: The Art of African Americans from Black Colleges and Universities, The Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts, Studio Museum of Harlem, New York, United-States, 1999–2001

Multidisciplinary artist.

Suzanna Ogunjami Wilson was a multidisciplinary artist best known for her paintings. She was active in the USA during the 1920s and 1930s, before moving to Sierra Leone in 1935. Her birthplace and origins remain a mystery. According to several written accounts, S. Ogunjami was born in Nigeria to an Igbo family in the late 19th century. However, the United States census records state that she was born in Jamaica, where she spent the early years of her life.

In the 1920s, S. Ogunjami studied at Columbia University’s Teachers College, earning a Bachelor of Science in 1928, followed by a Master of Fine Arts in Art Education in 1929. Her thesis focused on West African art and craft traditions. Between 1928 and 1934, her work was regularly exhibited in New York, notably through the support of the Harmon Foundation, which showcased her art alongside that of African American artists. In 1928, while still a student, she presented Sunflower, a still life painting. This work was shown again in 1933 by the Harmon Foundation, featured alongside pieces by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877–1968), Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998) and Laura Wheeler Waring (1887–1948). The Harlem Renaissance was in full bloom–a vibrant artistic and literary movement that emerged between the World Wars, bringing together African American artists and intellectuals who sought to portray modern Black life. In line with the ideas championed by writer Alain Locke (1885–1954) in his anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), S. Ogunjami drew inspiration from African cultures to shape her artistic vision. Her 1934 painting A Nupe Princess depicts a middle-aged woman from the Nupe royal family, adorned with a necklace in the colours of Pan-Africanism–yellow, black, green and red–symbolically merging the artist’s Nigerian and Jamaican heritages.

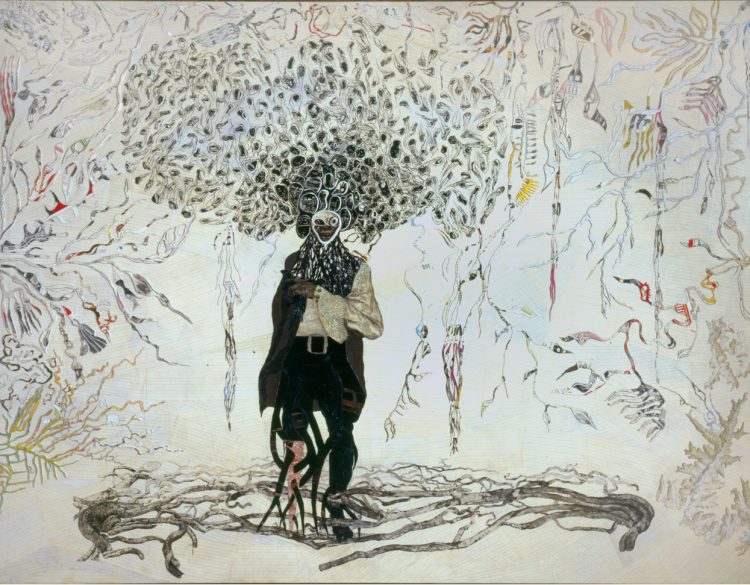

In December 1934, S. Ogunjami held her first solo exhibition at Delphic Studios Gallery in New York, an art space founded by patron and gallerist Alma Reed (1887–1966). The show featured jewellery, metal sculptures, and twenty-seven paintings, including portraits and floral still lifes such as A Nupe Princess, A Susu Beauty, Ekandayo and Watching for the Caravans. S. Ogunjami described the exhibition as the culmination of several years of study. The event was filmed by the Harmon Foundation and later included in the 1937 documentary A Study of Negro Artists, in which S. Ogunjami—likely aged forty-nine or fifty—appears on screen alongside her husband Matthew N. Ogunjami Wilson, a Krio Episcopal pastor whom she had married in the United States in 1916. Amongst the works on show was Full Blown Magnolia (1934), one of her few located and identified paintings as of 2025. Magnolias—symbols of perseverance, sensuality and refinement—are solitary plants native to both the Caribbean and the southern United States. The flowers are a recurrent motif in the work of Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960), the Alabama-born African American writer and key figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Magnolias appear in her first published short story, Spunk (1925), included in The New Negro, as well as in Magnolia Flower (1925), named after its main protagonist—the daughter of a Cherokee woman and an enslaved Black man.

In 1935, S. Ogunjami moved to Sierra Leone with her husband. While he became active in the Anglican Church in Freetown, she founded two art schools for children: the West African Normal and Industrial Institute in Freetown, and a second school located outside the city. Despite her departure, her work continued to be exhibited in the USA, including at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, the Mulvane Art Museum at Washburn College and the New Jersey State Museum. In 1960, Evelyn S. Brown, deputy director of the Harmon Foundation, wrote to Krio artist “Olayinka” Miranda Burney-Nicol (1927–1996) in the hope of tracing S. Ogunjami’s whereabouts – without success.

A Study of Negro Artists, black-and-white film, Harmon Foundation, 1937. In the 37 minute and 15 second version, Suzanna Ogunjami appears between 29:28 and 31:40

A Study of Negro Artists, black-and-white film, Harmon Foundation, 1937. In the 37 minute and 15 second version, Suzanna Ogunjami appears between 29:28 and 31:40