Suzanne Valadon

Rey Robert, Suzanne Valadon, Paris, NRF, 1922

→Georgel Pierre (ed.), Suzanne Valadon, exh. cat., musée national d’Art moderne, Paris, (17 March–30 April 1967), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1967

→Diamand-Rosinsky Thérèse, Suzanne Valadon, Paris, Flammarion, 2005

Suzanne Valadon, musée national d’Art moderne, Paris, 17 March–30 April 1967

→Suzanne Valadon, Pierre Gianadda Foundation, Martigny, 26 January–27 May 1996

→Suzanne Valadon et Maurice Utrillo, Pinacothèque de Paris, 6 March–15 September 2009

French painter.

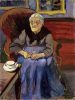

A self-taught painter, born of an unknown father and washerwoman mother, Suzanne Valadon is exceptional both in the quality of her work and her social and artistic career. The education of this poor child, entrusted to strangers, was brief. From the age of 11, she went from odd job to odd job in Paris, where she lived with her mother. After working briefly in a circus, she became a model for the artists in whose circle she moved: Puvis, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, Forain. In 1883, she gave birth to a child, Maurice, who was raised by her own mother. He would become the painter Utrillo, named after the journalist who claimed paternity it in 1891. Very quickly her son became one of her favorite models; she began to draw many familial scenes. The same year, she created a self-portrait in pastel, her earliest work surviving today.

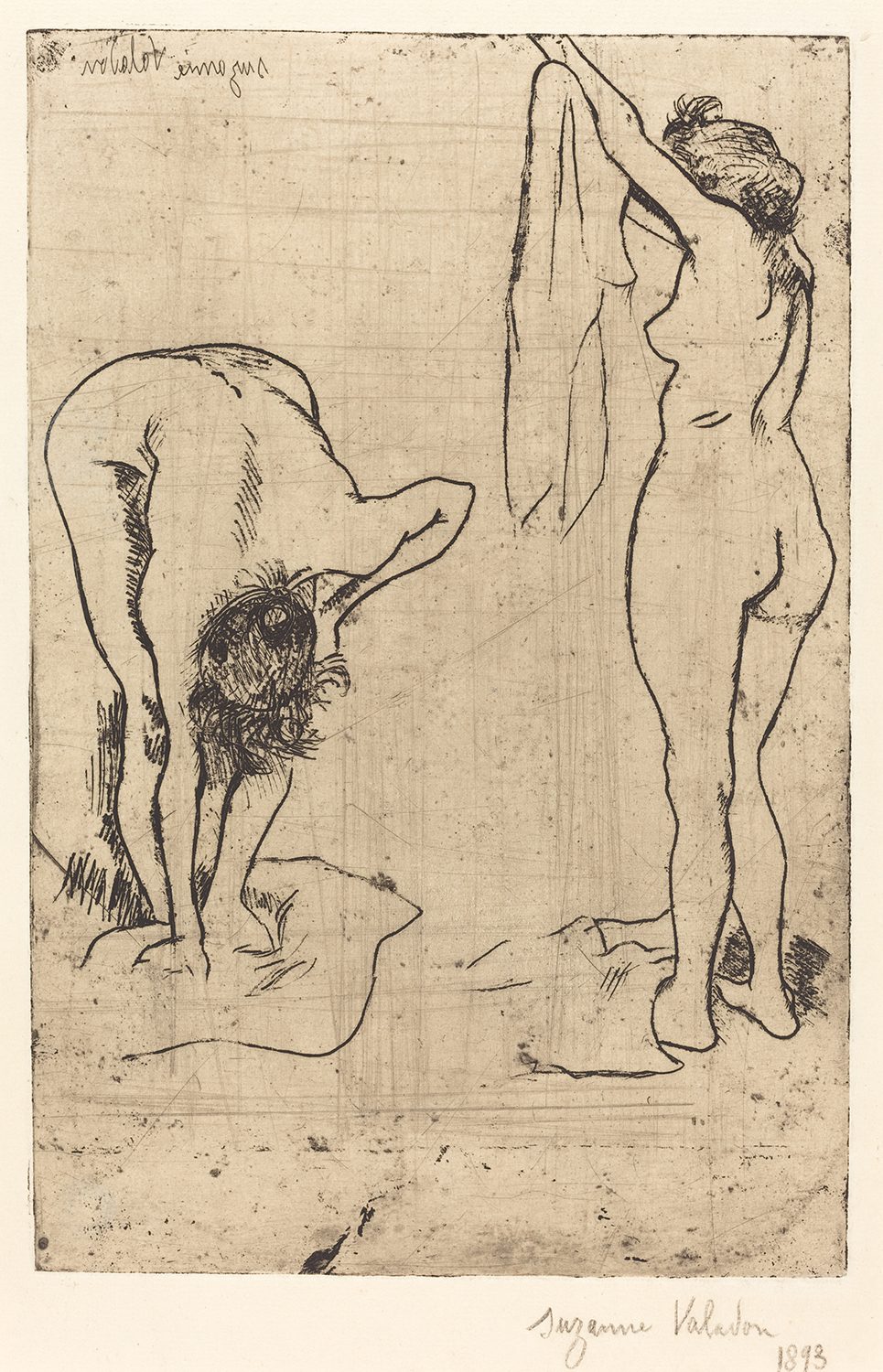

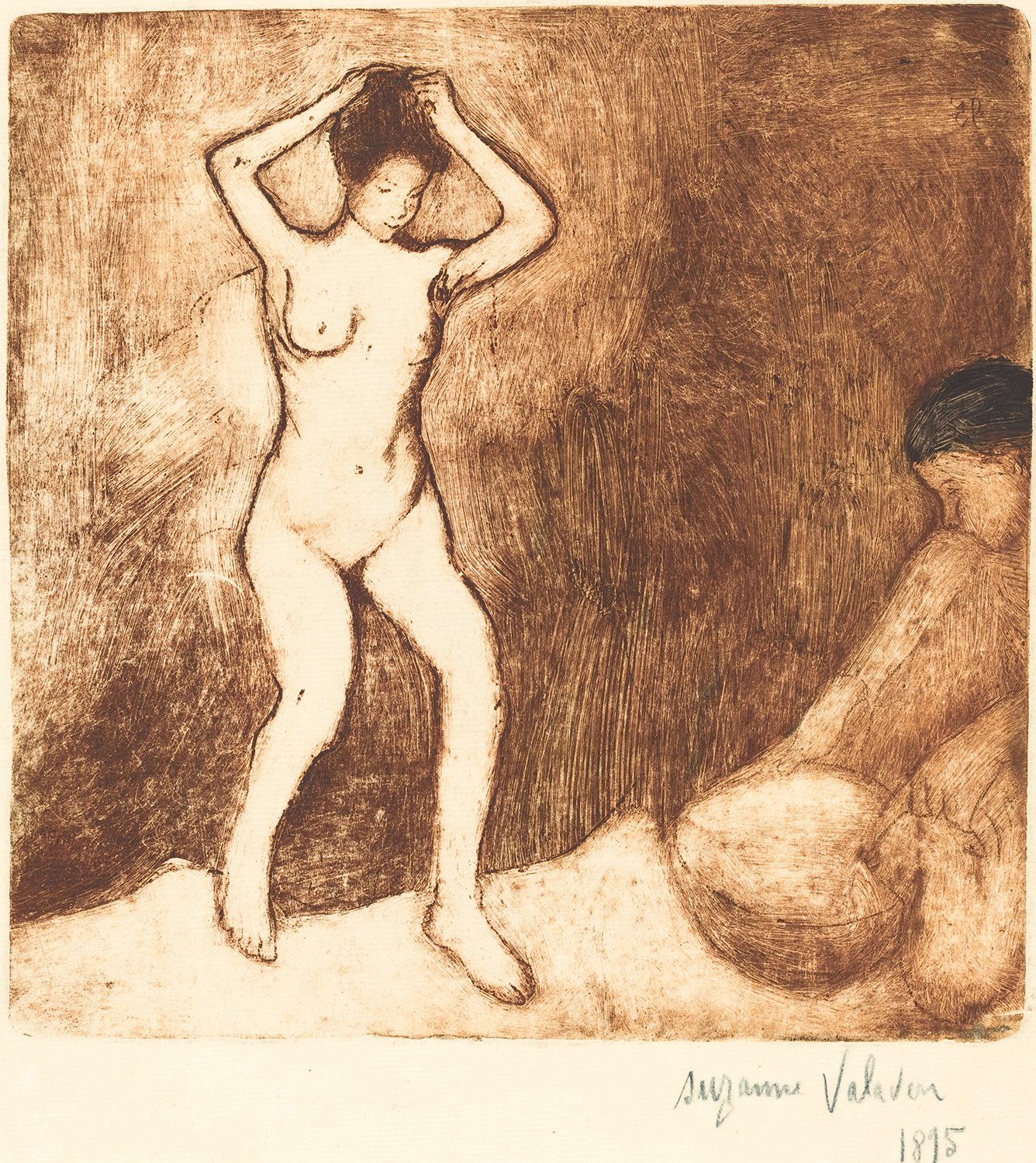

It was not until 1890-1891 that she painted his first oil, but her production remained, for the most part, drawings. In 1894, supported by sculptor Paul-Albert Bartholomé, she showed five drawings at the Salon of the national society of fine arts. Degas acquired one of them, then taught her intaglio engraving on his own press. In 1896, she married Paul Mousis. Her drawings and etchings were sold by the gallery Le Barc de Boutteville and Ambroise Vollard published her prints. The artist asked her female entourage to pose for her; dhe was interested in everyday gestures and movements, such as bathing, which she used to portray the body, both in physical fatigue, and tenderness.

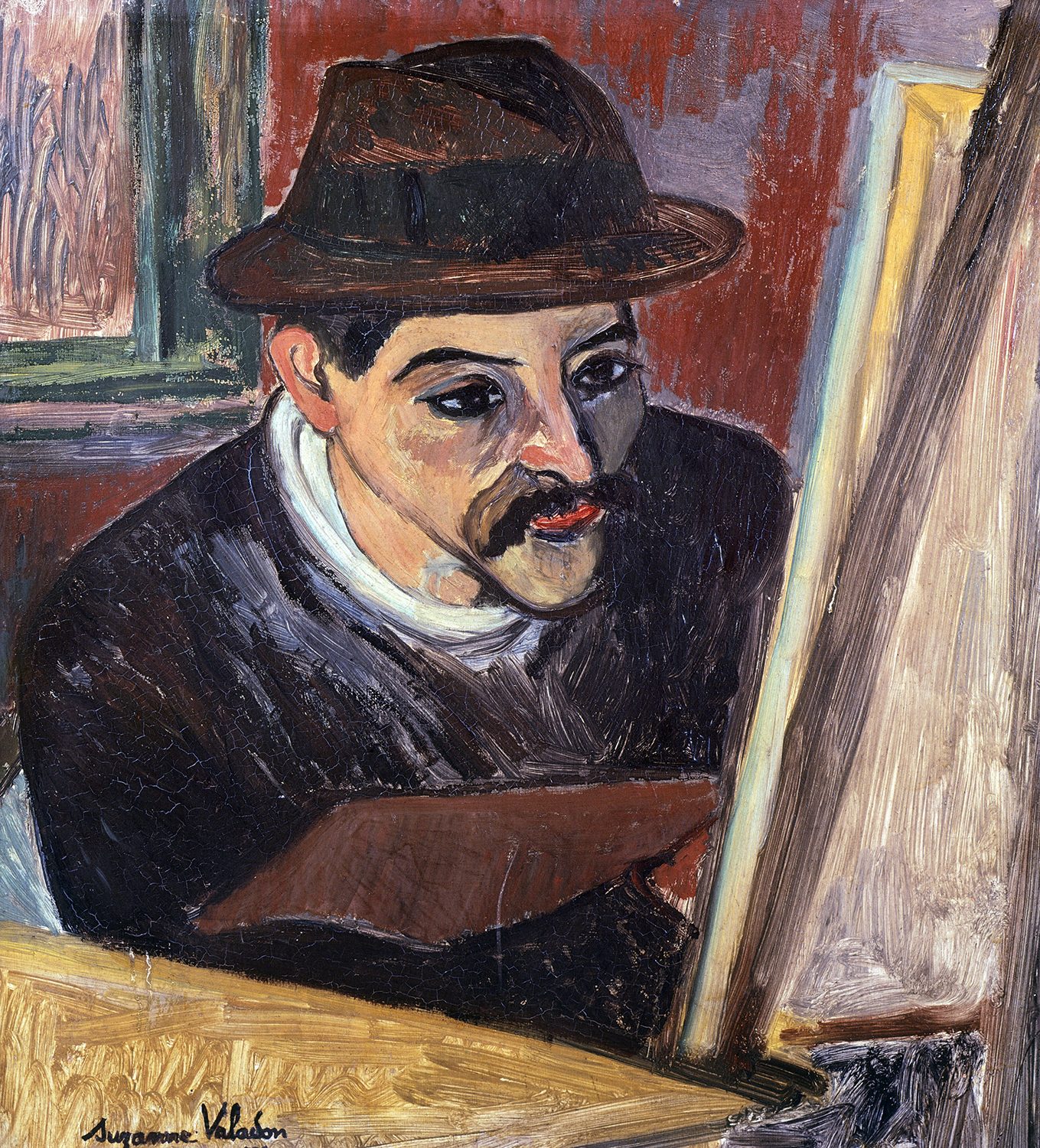

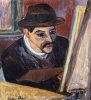

In 1909, she filed for divorce and moved to Montmartre with Maurice and her new companion, the painter André Utter. Her life then took a decisive turn. Concentrated more on painting, she was inspired by the Utter’s naked body: Adam and Eve (1909) presents the couple, naked, in the Garden of Eden. Thus Valadon became the first artist to dare to portray the male nude, painted full frontal. However, in order to show this painting at the 1920 Salon d’Automne, she had to hide Adam’s genitals behind a garland of fanciful leaves. This painting is in itself a statement of modernity and even a revolution in mores, because the artist not only portrays herself, but also man, the object of her desire, totally naked. In Le Lancement du filet (1914), less conditioned by education and social environment than most women artists of her time, she shows the pleasure she feels facing the male body, changing up the typical gender of the subject. In 1911, her first solo exhibition was held at the gallery of Clovis Sagot; following this, her works were regularly presented at the Salon d’automne and the Salon des independents, and by Berthe Weill, who steadfastly supported modern women artists. Shortly before the declaration of war in 1914, she married Utter. In 1920 she was recognized by her peers; she was named a member of the Salon d’automne, and some of her works were put on sale at the Hôtel Drouot.

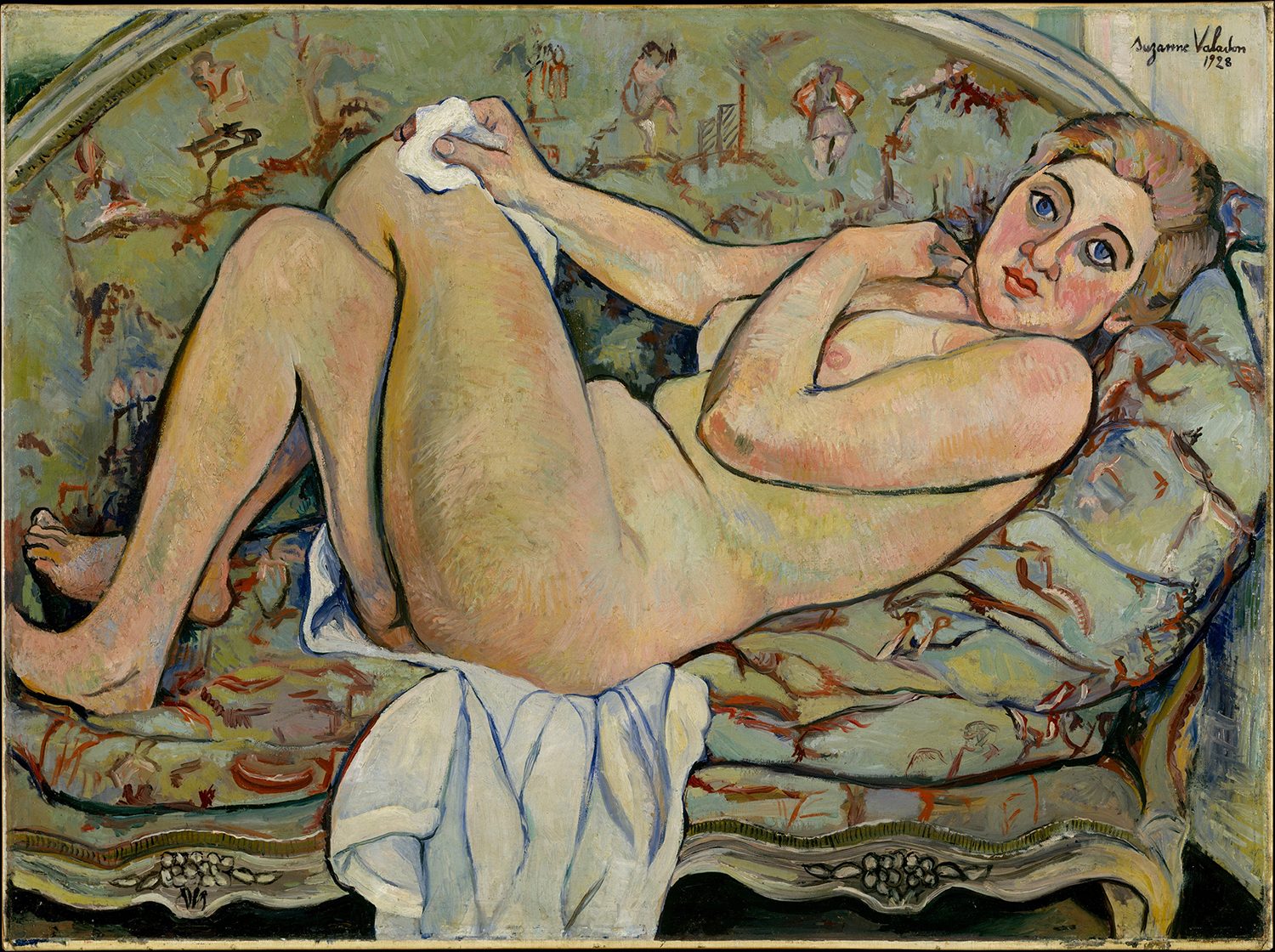

In 1923, Robert Rey published her first monograph. The same year, she dared to revisit the theme of the odalisque, so dear to her male colleagues, by making the reclining subject a mature woman, modern, dressed in pajama pants and a jacket, lost in thought smoking, two books within her reach main (La Chambre bleue). In 1929, the Bernier gallery hosted a retrospective of her drawings and engravings, completed by a few more recent works.

Starting in 1931, likely because of their great age difference, her relationship with Utter deteriorated. At that time, she painted herself naked and aging in Autoportrait aux seins nus (1931), an innovative piece in its representation of the body as it is, without complacency, but also without moral hindsight and reflection on a shameful or tearful age. Her work was shown most everywhere in Europe and across the Atlantic. From 1933, it became more difficult for her to paint, so she confined herself to drawing. At the request of the Modern Women Artists Group, she is regularly presented at their Salon. In 1937, the state bought many of her works, making her—a model of the self-taught painter—equal to those for whom she had so long posed. She died the following year.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017