Research

In France, in the 1970s, artists, critics and people interested in art were involved in feminist movements and established visual artists’ collectives which were busy for a decade.1 This article describes some of the new factors in this lengthy research: an unmagnified eye cast on motherhood, the use of textiles without any prior apprenticeship, a gendered vision of the history of classical art, and the words of former generations of immigrants, men and woman alike. These areas of interest link up with present-day preoccupations and encounter kinds of public keen to have another culture.

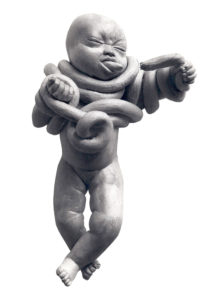

Dedans-Dehors / Jeu Jumelles, 1977-1978, plastic clay, about 15 cm/6 in. © Lou Perdu / ADAGP, 2016.

Dedans-Dehors / La langue maternelle, 1977-1978, terre plastique, env. 15 cm. © Lou Perdu / ADAGP, 2016.

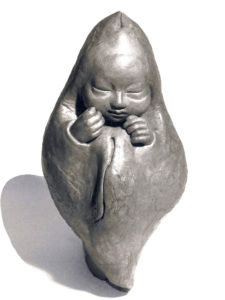

Dedans-Dehors / Bébé-graine, terre plastique, env. 15 cm, 1977-1978. © Lou Perdu / ADAGP, 2016.

Lou Perdu and Claire Bretécher, an unusual gestation

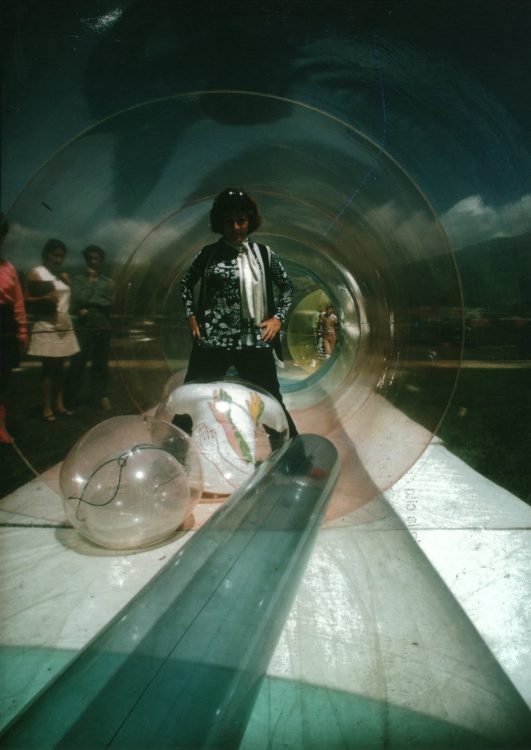

In that period when the Neuwirth law authorized contraception (1967) and feminist struggles led to the legalization of abortion (the Veil law of 1975), women acquired a mastery of their bodies and pregnancy became a choice. Among the various representations of motherhood,2 Lou Perdu focused on gestation, birth and the early months of human life. Perdues d’ELLE(1977–1978) and Dedans-Dehors [Inside-Outside] (1975–1980) appeared just when she was taking part in feminist struggles, in militant and artistic collectives

Dedans-Dehors is based on Lou Perdu’s own experience for recollecting and imagining that beginning of life. This process is steeped in psychoanalysis, a recurrent practice in feminist circles, which is also improved by this same feminist outlook. The internal vision of babies introduces them to that umbilical cord, by turns playful and brutalized. In an external vision, they are protected by colocynth-shaped carapaces.3 From the 1960s on, medical imagery was being developed and, in the 1980s, this led to a generalized use of foetal scanning, which reveals what used to be hidden, and does away with the boundary between inside and outside.4 Lou Perdu has no recollection of having seen these in utero pictures of foetuses. Made of clay, these fifteen babies are fragile and associated with elements which clearly call to mind every manner of sexual organ.

Entre deux eaux, 1995, 17 tadpoles, terracotta, 30 à 75 cm. © Lou Perdu / ADAGP, 2016.

L’Amatrice de limaces / L’Immaculée, 2009, 1 slug, terracotta, stand made of wood and plaster, 85 cm. © Lou Perdu / ADAGP, 2016.

The influences of psychoanalysis, feminist movements and scientific progress are all brought together in these sculptures which offer new ways of seeing the relation to life, which, without magnifying them, intermingles painful social and family experiments with tenderness. Associated with seeds and colocynths, they rejoin the plant kingdom. In the 1990s and 2000s, the series of tadpoles (Entre deux eaux [Sitting On the Fence]) and L’amatrice de limaces [The Slug-lover] carried on this exploration of symbols, from the round belly to the tadpole-spermatozoon and the drooling organ, which the artist connects up with lines penned by the poet Guillevic: “I respected myself / Even in slugs.”5 With regard to the artist’s work, we can pick out recurrent processes and themes, from little babies to recent videos of walking (Des marches [Walks]), which lead to an exploration of cracks and damp, dark places from which one must emerge, somewhere between gentleness and pain, infringing certain rules with an obvious relish. Between stigmatization and over-evaluation, bodies are still battle fields, which Lou Perdu deals with in an ironical spirit.

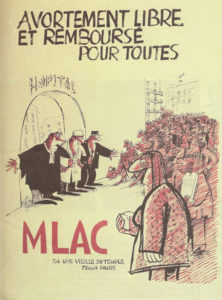

Avortement libre et remboursé pour toutes [Free abortion, reimbursed for all], MLAC, 1975. © Claire Bretécher

In the extrapolation of these representations, the drawings of Claire Bretécher, who opened the way for female creators of comic strips, aptly and cheekily outline the challenges involved in the mastery of procreation and the ambiguous positions of woman, their inner struggles, their contradictions, and their reactions to contradictory directives. For example, the illustrations Les Collabos [The collaborators] and Tota Mulier, taken from the album Les Frustrés [Frustration] (1973–1980), portray the stunned amazement of a woman looking at her female friend who, “after working for three years at the MLAC” (Le Mouvement pour la liberté de l’avortement et de la contraception [The Movement for Freedom of Abortion and Contraception]), aspires to a well-ordered life and is pregnant, and the torments of a woman who does not know if she is happy with her pregnancy.

Claire Brétecher supported the women’s liberation movement by way of posters, and in particular a magnificent poster for the MLAC6. The usual threesome featuring in feminist visuals, a doctor, a policeman and a judge, prevent the women in the poster from entering the hospital. The group of women who invade the space sport the red colour of anger and look sinister, well removed from the joyful imagery of feminist demonstrations. They are not laughing. One is rolling up her sleeves, spoiling for a fight, another is knitting, a reference to the barbaric methods of illicit abortions, a third is carrying a board in the shape of a gravestone, engraved with the words “dura lex sed lex”, “the law is hard, but such is the law”, something with which the woman in the foreground clutching a cobblestone seems to be taking issue, as she threatens the patriarchal trio with her stone, a reminder of May ’68.

In her later comic strips she challenges medically assisted procreation, the choice of being in control of your body, the endless questions that it ushers in, generational clashes, and the disparities between poor and rich countries in the matter of surrogate mothers. In Les Mères [Mothers] (1982), a father takes some beautiful photographs of a pregnant woman, who wants just one thing, to be seen as a seductive person, and ends up lashing out at him: “For the time being I admit it at a pinch, but when I’ve given birth, if you go on treating me like a mother, I’ll smash your face in!” Nowadays, the debate has to do with the possibility of gestation outside women’s bodies and wombs, known as ectogenesis, and the works of Lou Perdu and Claire Brétecher take on another meaning.

Skeins of multicoloured threads kept in the artist’s studio. © Hessie, photo credit: Fabienne Dumont.

Oui/Non[Yes/No], Trous [Holes] series, 1973, red thread embroidery on perforations, cotton fabric, detail. © Hessie, photo credit: Fabienne Dumont.

Untitled, undated, collage on paper, detail. © Hessie, photo credit: Fabienne Dumont.

Vital Weaves

Hessie, a spider’s web defying life

Meeting Hessie was difficult, because of her remove from the art scene and her problems with moving about. Today she hands over more elements of that art of survival, which she had talked about during an exhibition at the ARC in 1975, Survival Art – Hessie. The hundred or so works on fabric—buttons and threads, patiently arranged—re-emerge and make it possible to have another look at a little-known body of work in all its breadth. The entire production, most of it undated, seems to come from the 1970s and 1980s, with her creative phases becoming subsequently more random. The works using thread are the most visible, especially the series of plants, holes and wire nettings, but Hessie also glued eclectic elements on fabric, and made boxes, few of which are accessible, which all conjure up a rescue, a ritual involving safeguarding waste objects, which she wittily diverts from their destination.

Few people are acquainted with her involvement with women artists’ collectives, and her determined wish to exhibit four women in her studio in 1978,7 a secret studio-refuge that not even her children knew about, where, for a few rare years, she managed to open up an area of autonomous creation and life, far from family constraints. She nursed memories of Raymonde Arcier’s gigantic metal knitted works, Dorothée Selz’s sugar-coated framed pictures, and wrought-iron sculptures produced by Caroline Lee, not forgetting Mathilde Ferrer’s energy—a whole weft of friendship. A work on fabric found in her studio furthermore declares “Oui/ Non” [“Yes/No”], perhaps an echo to the Roe versus Wade referendum, which took place in 1973 in the United States, and whose ruling legalized abortion. Other affinities pushed her onto the side of anti-racist struggles, and the fight against living conditions imposed on exiled women and men of colour. Patiently, ears pricked to hear the noises of the world, and the progress being made by all the struggles, and to stop herself being overwhelmed by everyday chores and hang on to “a room of her own”, Hessie embroidered.

Le Filet [The Net], 1978, grey wool, detail. © Aline Ribière, photo credit: Marc Guiraud.

Les Mues [Sloughs], 2001–2006, algae, glue, flax thread. © Aline Ribière, photo credit: Vincent Monthier

The works borrowed the path of sewing and stitching, threads floating and creating repetitive motifs on the surface of the canvas, but she also captured objects in her canvases, on paper or on fine wire mesh, like a spider trapping its prey with glue. Mirrors, pieces of plastic, plants, coins and strange, poetic and surrealist arrangements emerge from these collages. A small match associated with a twisted thread seems to be laughing at life, and challenging it.

The story of Hessie reflects thousands of similar stories. She left Cuba and went first to the United States, then to Europe, surviving by becoming a dancer, working in cabarets and music-halls. Then, of her own accord, she started sewing, to make a skirt for herself. Over and above survival, she found herself involved in a creative act, which used the codes of her day and age, borrowing from textile art, Minimal art, Pop art, New Realism, concrete poetry, and a form of Surrealism and Dadaism, because, far from being detached from the world, Hessie was well-informed about what was going on around her. But because she saw her art as an act of resistance to the humdrum daily round, it was not imperative to exhibit.

Le Filet [The net], 1978, detail. © Aline Ribière, photo credit: Fabienne Dumont.

Les Mues [Sloughs], 2001–2006, detail. © Aline Ribière, photo credit: Fabienne Dumont

Aline Ribière, from nets to seaweed, trapped and then freed, in a loop

Where Aline Ribière is concerned, I was acquainted with the few dresses she produced in the 1970s. A visit to her studio in Bordeaux gave me a chance to discover other works, as well as come face-to-face with the objects themselves. Steeped in the protests of the day—those organized by feminists and conscientious objectors, as well as those of regionalists who wanted to vivre au pays or ‘live in their land’, Aline Ribière then made a net, knitted with grey wool, which she propelled into the air. The liberation contained in that powerful gesture, expressing a refusal of that straitjacket trapping her, reflected an energy peculiar to the feminist movement, even though she had the impression of not having been understood by the Women’s Liberation Movement. The artist grew up in a very female family environment, and claims an attachment to the way women express inner sensations.

Among the last series, dresses made with seaweed, at once fragile, crusted, both captivating and repulsive, conjured up that ongoing love-hate relationship between the artist and her dresses—a skin which protects, embellishes, and magnifies, and also cramps, holds back and confines at the same time. Aline Ribière called that series Les Mues (Sloughs, 2001–2006), a title which evokes putrefied, sutured flesh, and a carapace whose life has left it, so it falls apart. The forms of matter used also conjure up territories and maps, a whole geology of terrestrial crusts. The deterioration of the red and green seaweed marks the passage of time, which alters bodies, reminds us of our finiteness and, by way of the small tail affixed to the bottom of the dresses, evokes our animal origins. Through her dresses, Aline Ribière explores these states in their relation to the world roundabout. With Hessie, she shares a withdrawal from the world, a patient labour and a self-taught apprenticeship in sewing, which they both freely use.

Ris-Orangis (formerly L’immigration et la ville nouvelle [Immigration and the New City]), 1979. © Nil Yalter

Lapidation, 2009. © Nil Yalter.

Democratizing access to art

Nil Yalter, between East and West, a committed nomadism

Survival and sewing also lie at the heart of one of the first pieces produced by Nil Yalter after her arrival in Paris, and in any event the piece which, for her, would open the door to the European avant-garde scene. It was titled La Yourte ou Topak Ev (The Yurt or Topak Ev, 1973). She was in fact noticed by Suzanne Pagé, who showed her work at the ARC (department of “animation, recherche, confrontation”), the contemporary branch of the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art. Her work had never been exhibited in France since then, but it was shown in an exhibition at La Verrière, in Brussels,8 which then travelled to the Frac Lorraine.9 This latter show is enriched by the presentation of a whole series of objects, and is the artist’s first retrospective in France. Today aged 78, and after an uninterrupted career, it was time for recognition to do its work. As someone who has been involved, accomplice-like, for twenty years in the ups and downs of rediscoveries, I can well measure the significance of the essential texts which go hand-in-hand with these works. The analysis of the yurt, that nomad’s tent made by women in a context of forced sedentarization among the Turkmen peoples of central Anatolia, which is marvellously recounted by Yachar Kemal,10 is crucial for an understanding of the artist’s subsequent development.

Some projects, including the ten or so video tapes which gave the floor to immigrant populations in the 1970s and 1980s, have obvious and powerful echoes with our current situation.11 They help us to grasp the present in different ways, thanks to the history that is rewoven in aesthetic perspectives. With a gap of 40 years, Nil Yalter’s interest in violent and humiliating acts committed against women, whose phoney ancestral attributions she rails against, is still on-going. La Femme sans tête ou la danse du ventre (The Headless Woman or the Belly Dance, 1974), which spoke out against excision and promoted clitoral pleasure, represents a strange echo of Lapidation (2009), which enshrines the body of the artist and that of a young woman, killed for having loved a man whose religion was based on another current of Islam. Beliefs and human manipulations of myths and religions permeate Nil Yalter’s entire oeuvre, where the materialism hailing from her interest in ethnography and her involvement in communist Franco-Turkish cultural domains are mixed with a deep knowledge about the beliefs which also give human communities their structure. Where these sources of inspiration converge, she opened up a way which is still incomparable to this day, so well does she consolidate issues of feminism, class and gender, and all the ethnographic and socio-critical influences peculiar to the 1960s and 1970s.

Discours sur l’art [Discourse on Art], Antwerp, 1975. © Nicolas Lublin

Discours sur l’art [Discourse on Art], Paris, 1975 (with Dany Bloch at the centre). © Nicolas Lublin

Lea Lublin, a keen eye on what is implicit in the art world

The only approach that she does not exhaust lies at the heart of the work of another artist, our rekindled knowledge of whom has been made possible by the availability of her videos.12 Lea Lublin is actually close to Nil Yalter; they met amid the upsurge of feminist groups and the effervescent Paris art scene13. Lea Lublin uses video as a way of democratizing words about art, and as a way of challenging stereotypes linked with representations of women. So in November 1974, at the ARC 2, during the exhibition Video Art confrontation, and in February 1975, at the FIAC, she questioned art professionals and the public alike on the subject of art; she duly compiled these reflections in two tapes titled Discours sur l’art (Discourse on Art, 1974-1975). These questions are written out on large banners which she also takes into urban areas, for Lea Lublin defines art as a social praxis, and one in which we can question its component parts, and in particular the forms of discourse which surround it, in all social classes.

So, far from being exhausted, a line of research embarked upon twenty years ago is being ramified by precise and renewed analyses, which enrich the incomplete knowledge people used to have about the works of these six visual artists. Living memory is being permanently invented and forged. The art history factory is being operated with an ‘aware’ spirit, conscious of forms of discrimination in the development of visual culture, which people resist by producing other kinds of knowledge, and becoming interested in artists relegated to the sidelines, in order to offer access to another vision of the world, and underpin a legitimacy which is to the advantage of all generations.

Fabienne Dumont is an art historian, art critic and professor at the EESAB. Her thesis became a book, Des sorcières comme les autres. Artistes et féministes dans la France des années 1970 (PUR, 2014). Her interest in issues involving feminism and gender, as well as queer issues and questions of masculinity, prompted her to edit an anthology, La rébellion du Deuxième Sexe. L’histoire de l’art au crible des théories féministes anglo-américaines (1970-2000) (Les Presses du réel, 2011). She contributes regularly to collective publications and magazines. Some of the texts are referenced on the website of the Archives de la critique d’art. Her latest articles accompany the performances of TsunekoTaniuchi (fondation Hermès, Tokyo), the installation of Andrea Bowers (Espace culturel Louis Vuitton, Paris), the exhibitions of Marie Preston and Chercher le garçon (MACVAL), “L’étude de genre sous le prisme de l’histoire de l’art” for Universalia 2015 – Encyclopædia Universalis, and the exhibitions of Nil Yalter (La Verrière, Bruxelles ; FRAC Lorraine, Metz).

F. Dumont, Des sorcières comme les autres. Artistes et féministes dans la France des années 1970, Rennes, PUR, 2014.

2

F. Dumont, “La maternité sous divers points de vue”, Des sorcières comme les autres, ibid., pp. 285-294. This interest was revived by the preparation of a lecture, “De la grossesse à l’accouchement – Regards des plasticiennes sur la maternité en art contemporain”, cycle Histoire et pratiques autour de la naissance, École de Sages-femmes et association des gynécologues obstétriciens de la Région Centre, Tours, 17 December 2015 and the monitoring of Mélanie Damiens’s Midwife Master.

3

This representations are in line with the photographs of Lennart Nilsson, published in 1965 in A child is born (Lars Hamberger et Lennart Nilsson, Naître, Paris, Hachette, 1990).

4

Emmanuelle Berthiaud, Enceinte. Une histoire de la grossesse entre art et société, Paris, La Martinière, 2013, pp. 205-206.

5

Guillevic, Du domaine, Paris, Gallimard, 1977.

6

You can listen again to the evening devoted to Bretécher et son héritage, with Fabienne Dumont, Catherine Meurisse, Aude Picault and Matthieu Rémy, Centre Pompidou/BPI, 30 November 2015 here.

7

F. Dumont, “Hessie, un art textile minimal” and two excerpts taken from Des sorcières comme les autres, catalogue Hessie – Survival Art, 1969–2015, published by the galerie Arnaud Lefebvre, Paris, 2015, pp. 23-24, 114-115. Thanks to the work of Arnaud Lefebvre and Aurélie Noury, it is once again possible to view Hessie’s works, which have been restored—a valuable undertaking.

8

F. Dumont, “Les nomades de Nil Yalter. Des Bektiks de la steppe anatolienne aux passagers du Direct-Orient-Express”, Le Journal de La Verrière, no. 9, September 2015, pp. 8-17 (English translation).

9

F. Dumont, “La cosmogonie de Nil Yalter”, Nil Yalter, catalogue of the FRAC Lorraine, Metz, 2016, pp. 7- 35 (English translation).

10

Yachar Kemal (1923-2015) was a Turkish writer and journalist, of Kurdish origin, famous in Turkey for having recounted working-class life and his political involvements against the oppression of different populations by the government. Nil Yalter has used excerpts from the novel The Legend of the Thousand Bulls in the context of her nomad’s tent.

11

In 2010, I started to draw up an inventory of the artist’s video tapes, so that they could be digitized. Since then, Nil Yalter has been permanently reworking and recycling these tapes. They are still crucial evidence of the immigrant experience in the 1970s and 1980s, but also represent bonds woven between eastern and western traditions from a feminist and socio-ethnographical viewpoint. I am currently working on a monographic essay on this subject, Nil Yalter. À la confluence des mémoires migrantes, du féminisme et du monde ouvrier.

12

In 2011, I worked on a detailed inventory of the artist’s video and audio tapes, with the aim of persuading the Bibliothèque nationale de France to go ahead with their digitization. The Lea Lublin collection thus created, and recently brought to public notice, offers a direct access to her oeuvre. This safeguard is helping me, today, to undertake more in-depth analyses.

13

It is possible to view a lecture I gave at the Centre Pompidou, “Bandes de femmes”, Vidéo et après, Paris, 13 April 2015, available here.

Fabienne Dumont, "News About One or Two Witches in France in the 1970s." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/actualites-de-quelques-sorcieres-des-annees-1970-francaises/. Accessed 13 February 2026