Review

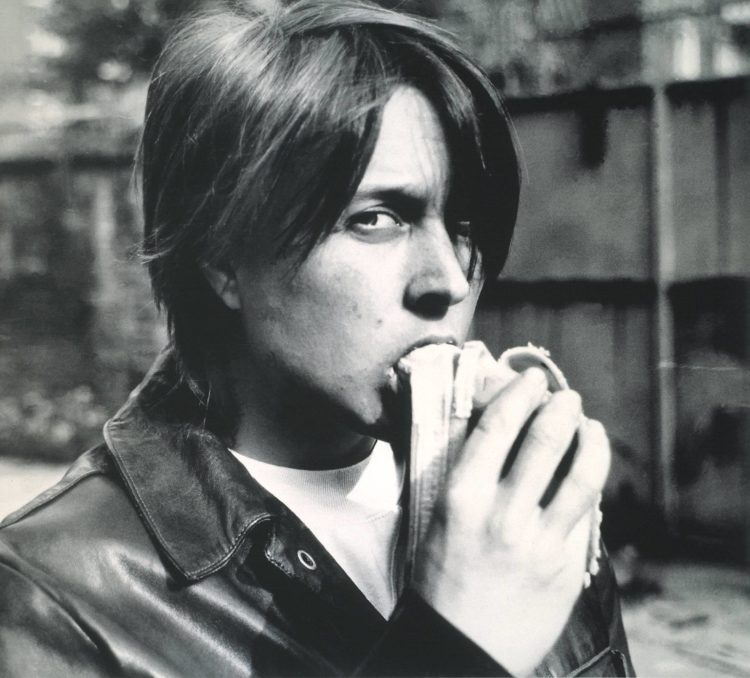

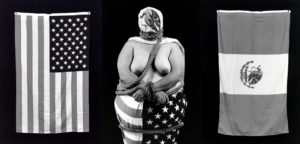

Regina Vater, Tina America, 1976, documentation of performance: twelve black-and-white photographs, 43.8 × 80.3 cm, 17 1⁄4 × 31 in., Courtesy Henrique Faria, New York, © Photo: Maria da Garça Lopes Rodriguez

“I am a bad hombre… and a nasty woman,” proclaimed Mexican feminist artist Mónica Mayer (b. 1954) at the recent symposium “The Political Body in Latina and Latin American Art,” held in conjunction with the opening of “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985” at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

Featuring 120 artists from 15 countries, “Radical Women” is the first large-scale survey to focus on women of Latin American descent, including Chicana and Latina artists from the United States. Coming on the heels of a similarly groundbreaking historical survey of African American women artists from roughly the same period, “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85,” which closed at the Brooklyn Museum in New York the same weekend “Radical Women” opened, the show aims to widen the art historical canon in much the same way the global survey of women’s art “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution” did ten years ago.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants), 1972, suite of seven estate color photographs, four sheets: 13 1⁄4 × 20 in. (33.7 × 50.8 cm); three sheets: 20 × 13 1⁄4 in. (50.8 × 33.7 cm), Courtesy The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC and Galerie Lelong, New York

“Radical Women” is just one of approximately 70 exhibitions organized by Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA (Los Angeles/Latin America), the behemoth Getty-funded initiative of Latin American and Latinx themed art shows taking place across Southern California in the fall of 2017. It is also one of several PST: LA/LA shows to examine not just ethnic and cultural identity, but also gender and sexuality and the myriad ways women and queer artists—often doubly marginalized by their ethnic identity and their gender and/or sexual orientation (even within their own communities)—confront issues around sexuality, violence, marginalization, and the body to stake a claim to the visibility and validity of their own subjectivities and experiences.

“Radical Women” curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta focus on “the political body,” organizing their impressive historical survey thematically, rather than by country or chronologically, including sections such as “Body Landscape,” “Resistance and Fear,” and “The Erotic.” Though they acknowledge that many of the artists in their show did not self-identify as feminists (feminism was long seen as taboo in many Latin American countries), they nonetheless read a feminist agenda in the works on view. Even so, their use of the term “radical” does not always imply political radicality, or even necessarily feminist politics. For them, “radicality” is also evident in the experimental strategies and new media these artists helped pioneer including video art, performance and body art, and conceptual art.

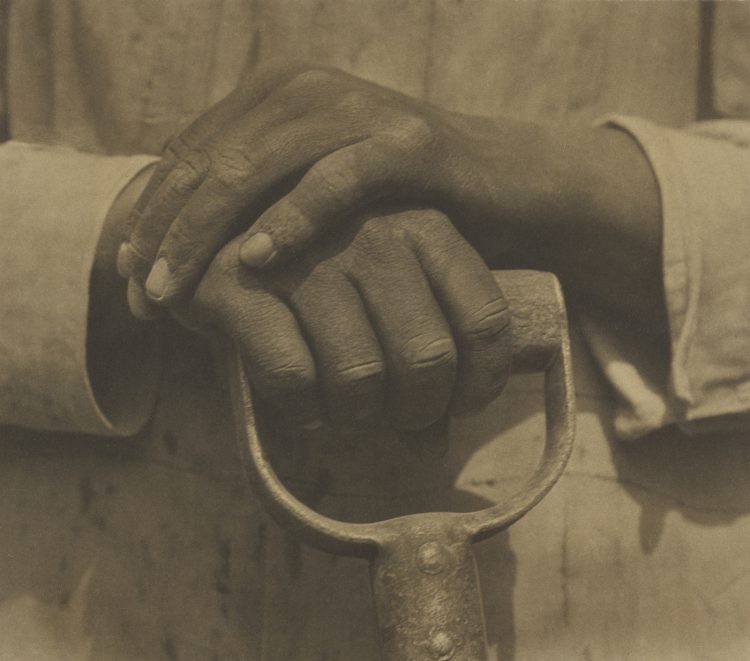

Letícia Parente, Marca registrada (Trademark), 1975, video black and white, sound, 10’30’’, Courtesy Galeria Jaqueline Martins, © Letícia Parente

Take for instance Brazilian video artist Letícia Parente’s (1930-1991) black and white video Trademark (1975), made at the apex of the dictatorship in Brazil, depicting the artist sewing the words “MADE IN BRAZIL” (in English) with thread into the sole of her naked foot, appropriating a craft traditionally associated with women’s work—sewing—to critique U.S. economic imperialism in Brazil, as well the objectification of the female body (like a product for sale, she is trademarked).

Peruvian artist Teresa Burga’s (b. 1935) installation Self-portrait. Structure. Report, 9.6.1972 (1972), comprised of drawings, diagrams, photographs, and medical records of the artist tacked to the walls of a small room, also politicizes the artist’s body. First created and presented in 1972 under Peru’s left-leaning military regime (1968–1980), Burga’s conceptual self-portrait transforms what Benjamin Buchloh has termed an “aesthetics of administration” into what Amanda Suhey and Dorota Biczel described as an aesthetics of bureaucracy, the concerns of conceptual artworks in the Latin American context that respond to state bureaucracies and authoritarian regimes, specifically the ways that disciplinary systems of surveillance attempt to standardize bodies and codify subjectivities as modes of control.

Other works challenge stereotypical gender roles and media representations through photography, such as Brazilian conceptual artist Regina Vater’s (b. 1943) Tina America (1976), a series of black and white portraits of the artist in different costumes, representing different middle-class Latin American female stereotypes, anticipating by one year Cindy Sherman’s more well-known Untitled Film Stills series (1977–1980).

Live performances and participatory projects are on view throughout the run of the exhibition, including Mónica Mayer’s interactive work, The Clothesline (1978/2017), a rack positioned outside the Hammer’s bookshop composed of pink cards clipped with clothespins to lines, posing provocative questions such as “Have you ever been sexually harassed at school or university?” and “What have you done to fight sexual harassment in Los Angeles?” with anonymous handwritten answers by gallery-goers—a disturbing, poignant, and empowering response to the ways women experience gender oppression in their everyday lives.

Paz Errázuriz, Evelyn, 1982, from La manzana de Adán [Adam’s apple] series, 1982–90, gelatin silver print, 39.5 × 59.7 cm, 15 9/16 × 23 in., Courtesy Paz Errázuriz and Galería AFA, Santiago

The curators’ assertion in their introductory catalogue essay that they dispute “essentialist positions on the feminine” is not always apparent when confronted with works that associate “the feminine” with the earth—as in Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta’s (1948–1985) Rock Heart with Blood (1975), a super-8 film in which the artist, naked, pours red paint over a heart-shaped rock before lying facedown into an imprint of her body in the ground—or with organic forms and fluids—as in Venezuelan duo Yeni y Nan’s Integrations in Water (1981), documentation of a performance in which the artists clad in white unitards roll around in plastic bags filled with water, as a symbol of femininity, birth, and transformation. Such strategies were typical of second wave feminist art, but were later challenged by third wave feminists and queer theorists in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond.

Gender binaries, though interrogated—as in Mendieta’s Untitled Facial Hair Transplants (1972)—are also left largely intact in the works of the artists on view, with the exception of Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz’s (b. 1944) Adam’s Apple series (1982–1990), an intimate and compassionate series of photographs documenting the inhabitants of a “transvestite brothel.” However, transgendered women only appear as objects of the gaze, not as authors.

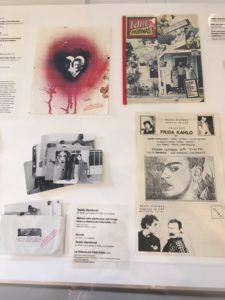

Installation view, Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., ONE Archives’ Gallery, © Photo: Gillian Sneed

Installation view, Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., ONE Archives’ Gallery, © Photo: Gillian Sneed

While “Radical Women” struggles to fully address “queer” in relationship to women’s art practices of the 60s–80s, by contrast, Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., organized by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Frantz and displayed over two sites—MOCA Pacific Design Center and a nearby pop-up space, ONE Gallery (operated by the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives)—does just that. It features experimental artworks in a variety of media made between the 1960s and early 1990s—a period framed by the Chicano Moratorium, feminist movement, and gay liberation on one end and the culture wars and AIDS crisis on the other—by more than 50 LGBTQ and Chicanx artists (a term used to avoid male/female gender binaries that the curators curiously do not use).

The works in the show evince a DIY and de-skilled aesthetic that is less oriented towards the aesthetics of institutional art, and more engaged with radical alternative communities and scenes. This beautifully curated and compelling exhibition—organized into sections with titles like “Chicano Chic,” considering fashion and gender performance, “Art Meets Punk,” looking at alternative spaces and collectives, and “AIDS activism,” considering how the AIDS crisis intersected with the Chicano and Gay Liberation movements—includes works by several artists who succumbed to HIV/AIDS and many who have not been shown publicly since the 1990s.

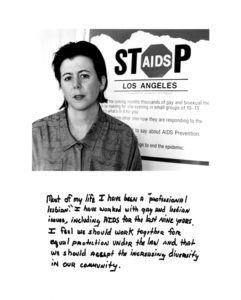

Laura Aguilar, Judy, 1990, from the Latina Lesbians series, 1985–91, gelatin silver print, 35.6 x 27.9 cm, 14 x 11 in., Courtesy Laura Aguilar

In addition to painting, conceptual projects, and performance documentation, the show includes a rich array of ephemera, archival materials, zines, and mail art, and presents exciting discoveries, including the late 1970s and early 1980s queer punk band Nervous Gender, featured in a vitrine displaying collaged posters advertising their shows, and the chance to listen to their music on headphones.

One artist included in Axis Mundo—Chicana lesbian photographer Laura Aguilar (b. 1959)—is also featured in a noteworthy solo exhibition organized by Sybil Venegas, “Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell.” The first comprehensive retrospective of her work, the show is located on the Vincent Price Museum at the East Los Angeles College campus, the artist’s alma mater. In her photographs, Aguilar documents the Chicanx queer community and her own expansive and exuberant body, often using nudity to express and validate queer subjectivities.

Laura Aguilar, Three Eagles Flying, 1990, 3 gelatin silver prints, 24 x 20 in. each, Courtesy Laura Aguilar and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, © Laura Aguilar

Arguably her most iconic work—and perhaps the most relevant in the Trump era—is Three Eagles Flying (1990), a large-scale, horizontal, black and white photograph depicting at center Aguilar’s partially nude body, her head wrapped, her lower body draped with an American flag, and her ample breasts and torso bound by ropes, flanked on the left with an unfurled American flag, and on the right, a Mexican flag. Like many Chicanx who occupy the borderlands, she straddles a liminal space between two realities, trapped and bound, but defiantly asserting her presence, despite limitations imposed on her by the state and hegemonic systems of oppression.

The exhibition’s third floor galleries are entirely populated by her landscape/nude self-portraits, evocative in some ways of Ana Mendieta’s imbrications of her own nude body with the land; however Aguilar’s corpulent body does not conform to traditional beauty standards as did Mendieta’s, rendering them a radical act of self love that expands notions of beauty to include all kinds of bodies and bodily expressions.

In addition to these, there are many more PST: LA/LA museum and gallery exhibitions dedicated to women and exploring issues around sexuality. Collectively, what these exhibitions highlight are the myriad strategies taken by “nasty women and bad hombres” across the Americas to explore the intersections of gender, sexuality, and cultural identity, the alternative networks and communities they forge, and the experimental approaches they marshal to confront exclusion and oppression. These artworks and exhibitions could not be more urgent. As the current political climate in the U.S. and in many places across Latin America have demonstrated, there is a continued need for understanding and celebrating the intellectual and cultural contributions of Latin American and Latinx/Chicanx women and LGBTQIA communities.

En référence notamment aux propos de Donald Trump pendant la campagne électorale américaine, lorsqu’il a qualifié de « bad hombres » (mauvais hombres) les ressortissants mexicains et de « nasty wowan » (femme odieuse, déplaisante) son adversaire démocrate Hillary Clinton.