Research

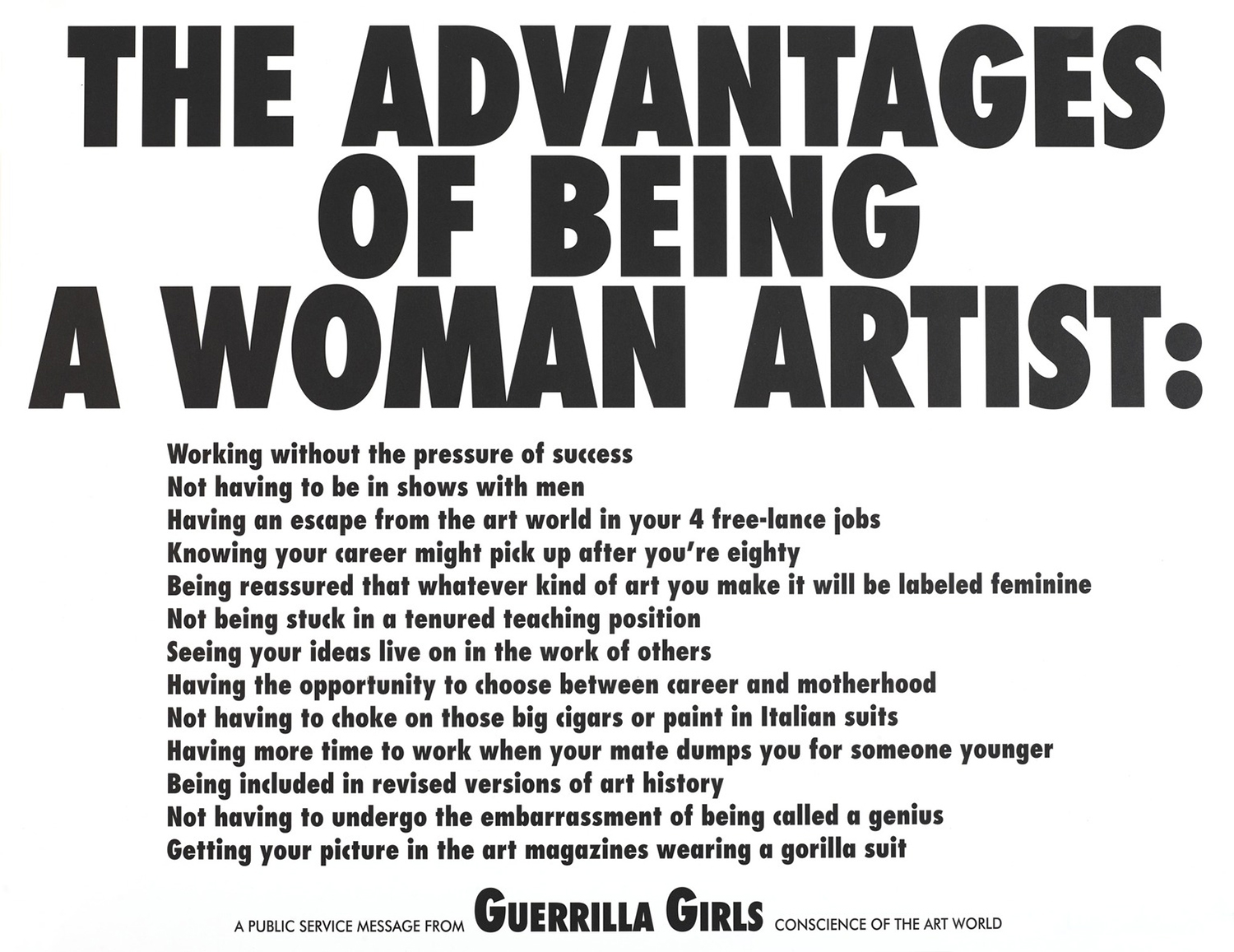

Guerrilla Girls, The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, 1988, print, 46 x 55.6 cm, © Brooklyn Museum.

“If the female function is not enough to define woman, and if we also reject the explanation of the ‘the eternal feminine’, but if we accept, even temporarily, that there are women on the earth, then we have to ask: What is a woman? […] If I want to define myself I first have to say, ‘I am a woman’; all other assertions will arise from this basic truth.”1

Group Portrait of the Women Weavers in their Bauhaus Workshop, 1928, © Photo Lux Feininger, Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin

“What is woman? Panic, general alarm for an active defense! Frankly, it’s a problem the lesbians don’t have because of a change of perspective, and it would be incorrect to say that lesbians associate, make love and live with women, since ‘woman’ only has meaning in heterosexual systems of thought and heterosexual economic systems. Lesbians are not women.”2

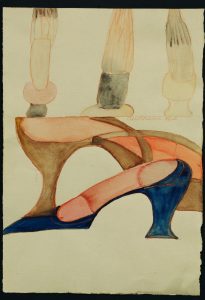

Carol Rama, Opera no. 47, 1940, watercolour and pastel on paper, 34.5 x 24.5 cm © Photo: Pino Dell’Aquila © Archivio Carol Rama, Turin

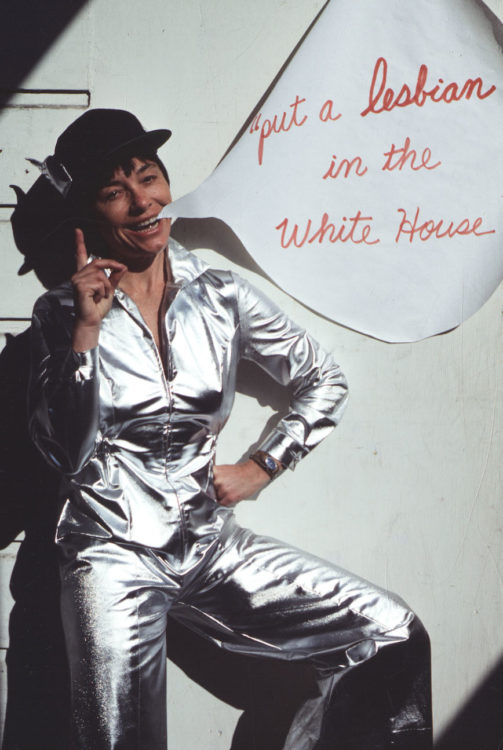

The research we have undertaken to examine the lack of non-heterosexual and/or transgender artists on the AWARE website (a numerical shortfall, but also a lack of biographical details for certain artists that would make it possible to construct lesbian and queer lineages) prompts us to ask legitimate questions about why a category called “woman” needs to exist at all where artists are concerned.

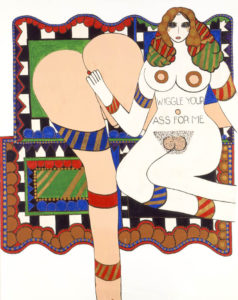

Until today, generations of woman artists have sought to disidentify themselves from a category created for them,3 while their male colleagues had no adjective associated with their function. If we don’t talk about “male artists” it is because the artist is understood by default to be male in the hallowed history of art.4 Consequently, women who want to give themselves the status of artists are caught up in a paradox: denying the supposed particularity of “being a woman” does not allow them to be included in a determinedly male universalist canon. The title of “great artist”, to paraphrase Linda Nochlin, is denied them, as they are victims of sexist prejudice directed at art made by women, whether or not they have decided to assert that they belong to a group called “women”. The wool sculptures of Sheila Hicks (born 1934) have long been relegated to the domain of decorative art, a distinction that is itself the product of 19th-century avant-gardes.5 The provocative sexual art of Carol Rama (1918-2015) and experiments with non-binary genital representation performed by Dorothy Iannone (born 1933) were censored throughout their lifetimes,6 while their male contemporaries were doing a roaring trade sexualising women’s bodies to celebrate male heterosexual impulses.

The relatively recent conquests of feminism, particularly in art histories, get us out of this rut: stating that one is an artist and a woman is, in some cases, to earn a position that the politics of representation has struggled to obtain. Thus, litle by little, it may become positive to call oneself “woman” and “artist” and to ride a rising tide for which several generations of women have fought.7

Sheila Hicks, Atterrissage, Landing, 2014, pigments, acrylic fibres, 480 x 430 x 260 cm, variable dimensions, © Photo: Zarko Vijatovic, © Galerie Frank Elbaz, Paris, © ADAGP, Paris

This difficulty around the assertion of identity as a woman or a woman artist engenders an existential doubt: what, ultimately, is a woman? Recalling, with the help of Simone de Beauvoir and Monique Wittig, that it is a construct that needs to be denaturalised leads us to question its current relevance. If “one is not born a woman but becomes one” and if “lesbians aren’t women”, what is the point of continuing to lay claim to the word?

Research on transidentities8 published since the 1990s has made it possible to establish that the presence of female genital reproductive organs in a body does not equate to female identity.9 We continue to use the two main categories arising from sexual difference even though the words “man” and “woman” struggle to embrace a multitude of realities. It is very tempting to abandon the exclusive use of the word “woman” as certain English-speaking militants have suggested by popularising the term “womyn” in the 1970s or more recently that of “womxn”, a word used in antiracist queer and transgender circles and considered more inclusive.The Black and transgender women who fought for a place alongside white cisgender women in late twentieth century feminist struggles are far from having relegated the term “woman” to the past, however.

Untitled (“I sell the shadow to support the substance.”), ca. 1864, albumen print mounted on paper, 10 x 6.2 cm © Library of Congress Washington

The African-American art critic and thinker bell hooks, in her book Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, published in 1981, denounces the fundamentally racist nature of American feminist movements.10 In all fields, feminist struggles have presented the experience of white women as if it were the experience of all women and made non-white experience invisible, which has made it possible to deny the identity of women of colour. These thoughts are present in the speech made by Sojourner Truth at the Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851. Several times during her address, the militant abolitionist was said to have asked the audience: “Ain’t I a woman?,”11 pointing to the de facto exclusion of woman slaves from discussions on women’s rights. In her book, bell hooks recounts the history of this exclusion, showing that the success of civil rights and antiracist movements in the United States relied on a patriarchal tradition. Similarly, in feminist movements, the analogy with slavery used to describe the lot of womenpropagated the idea of the mutually exclusive nature of two identities—as if slaves had somehow not been victims of oppression because they were women.12 In her introduction to the French edition bell hooks’s book, the filmmaker Amandine Gay stresses the need to question the intersectionality of feminism rather than its inclusiveness.13 Intersectional feminist thought makes it possible to articulate several systems of oppression and not place one form of oppression in the orbit of another supposedly more central or essential one. bell hooks shows that Black women have suffered simultneously from forms of sexism and racism that have perpetuated stereotyped perceptions of identities until the present day.14

The inclusion of trans women in non-mixed feminist circles is a question that has agitated feminists for over forty years. In 1979 the radical feminist author Janice Raymond described her fear of the supposed destruction of feminist and lesbian movements by trans women who would continue to introduce “masculine energy” into non-mixed spaces, aiming to cancel out the progress made by feminist movements.15 This somewhat paranoid and unjustified opinion was supported until 2015 by the important Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, a non-mixed lesbian festival that continued to exclude trans women until controversy seems to have put an end to its existence. In France in 2020, Marguerite Stern,16 a former femen who initiated collages denouncing violence against women, relaunched this form of transphobic feminism whose adherents are dubbed TERFs (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists).

Dorothy Iannone, Wiggle your Ass for Me, 1970, oil on canvas, 190 x 150 cm, © Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Tate Modern collections, London, Great-Britain, Courtesy the artist and Air de Paris, Romainville

Several trans women have raised their voices to combat this type of exclusion and discrimination. In 1987 Sandy Stone, a student of the biological historian and feminist thinker Donna Haraway, published The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto in response to Janice Raymond’s arguments, a pioneering text in trans studies.17 Following this, Julia Serano’s book Whipping Girl describes a genealogy of representations of trans people in transphobic cisgender cultures, especially the particular form of sexism that oppresses trans women, namely transmisogyny.18 She also discusses the concept of “experiential gender”, which reflects different experiences of womanhood. “By insisting that we trans women cannot possibly know what it’s like to ‘feel like a woman’, they’re the ones being presumptuous, both by arrogantly assuming that other women experience femaleness the way they do. … Any claim that one has superior knowledge about womanhood is fraught with gender entitlement and erases the infinite different ways for people to experience their own femaleness.”19

Julia Serano’s book is a manifesto for intersectional transfeminism and the widespread use of the word “woman” to describe diverse life experiences. The word “woman” endures for us today not as the only counterpoint to the word “man” in a binary approach to existence, but also as a term that has been nourished by debates that have animated feminism since Sojourner Truth’s speech. The term “woman artist” thus affords new reflexive potentialities: it no longer aims to describe a simplistic biological reality, instead acknowledging a political minority for artists that allows us to analyse the place of their work in history, measured against their relative positions with regard to privilege and discrimination.

Beauvoir Simone de, The Second Sex, trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (New York: Knopf, 2010), pp. 4-5.

2

Wittig Monique, The Straight Mind and Other Essays (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1992).

3

The concept of disidentification has been explained in depth by José Esteban Muñoz in his seminal book Disidentifications. Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

4

Griselda Pollock, “The Story of Art is an illustrated Story of Man”, in Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art’s Histories (London: New York, Routledge, 1999), p. 24.

5

Let us remember that the Bauhaus, which upon its creation in 1919 stated that there was to be equality between men and women, separated the sexes in 1920 by “reserving” its weaving workshop for women.

6

See the recently republished Story of Bern by Dorothy Iannone (Zurich: JRP, 2019), an edifying account of censorship organised by Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) and supported by men invited to the same exhibition.

7

Among historic American feminist initiatives are the Guerrilla Girls, the AIR Gallery in New York and the feminist programme at CalArts in California.

8

For instance the work of Leslie Feinberg, Julia Serano and Pat Califia in English and Sam Bourcier in French.

9

If sex is biological, gender is the result of socialisation, of a social and cultural construct. In the social sciences, queer and feminist studies challenge normative binary categories that are commonly held to be natural, innate or obvious (man/woman, male/female, heterosexual/homosexual).

10

“Every women’s movement in America from its earliest origin to the present day has been built on a racist foundation, a fact which in no way invalidates feminism as a political ideology.” bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1981).

11

Whether this emblematic phrase was in fact uttered in Sojourner Truth’s original speech is now subject to debate. See:https://www.thesojournertruthproject.com/

12

In the United States, but also in France. We are put in mind, for example, of the anthem of the French Women’s Liberation Movement (1971): “Depuis la nuit des temps, les femmes, Nous sommes le continent noir. Debout femmes esclaves. Et brisons nos entraves. Debout ! debout !” (Since the dawn of time, women, We are the black continent. Stand up, woman slaves. Let us break free of our shackles. Stand up! Stand up!)

13

Gay Amandine, “Préface”, in bell hooks, Ne suis-je pas une femme ?, trans. Olga Potot (Paris: Cambourakis 2015).

14

In Aint’ I a Woman bell hooks notes three stereotyped characters: the castrating masculine matriarchy, the obese asexual Mamma, and the Sapphire, the female incarnation of evil.

15

Raymond Janice, The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1979).

16

CheckNews, “Quel est le point de départ de la polémique sur la place des trans dans le féminisme ?”, Libération, February 13, 2020.

17

Stone Sandy, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto”, in Body Guards. The Cultural Politics of Gender Ambiguity, eds Julia Epstein and Kristina Straub (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp. 280-304.

18

Serano Julia, Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity (Seattle, WA: Seal Press, 2007).

19

Ibid., p. 227.

20

Ibid., p. 107.

Born in 1979, Isabelle Alfonsi is a graduate of the Institut d’Études Politiques in Paris and University College, London. In 2009 she created Marcelle Alix, a contemporary art gallery in the Belleville district of Paris, which she runs with Cécilia Becanovic. Since 2014 she has given talks on the lineage of contemporary queer art, sometimes in drag. Her book on the history of feminist art on the subject, Pour une esthétique de l’émancipation, was published by Éditions B42 in Paris in 2019.

Isabelle Alfonsi, "Should We Still Be Laying Claim to the Word “Woman”?." In , . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/devons-nous-encore-revendiquer-le-mot-femme/. Accessed 31 January 2026