Review

Huguette Caland, Various works, 1971-1995, mixed material, Courtesy Venice Biennale, © Photo: Italo Rondinella

The Venice Biennale started on May 13th under the aegis of guest Curator Christine Macel. The exhibition in the Giardini Central Pavilion and Arsenale venues brings together 120 artists from numerous countries displaying their works under the festive theme of “Viva Arte Viva”. A hymn to art and its ability suggest us reflecting on the world and remodeling it, in particular in this uncertain worldwide political climate. The event, for which the statistics show the strong presence of women and non-European artists – as much in the national pavilions and the main exhibition as in the collateral events –, seems to underline the openness of this 57th Biennale to a wide range of sexual and cultural identities.

Anne Imhof, Faust, 2017, Courtesy Venice Biennale, © Photo: Francesco Galli

Anne Imhof, Faust, 2017, Courtesy Venice Biennale, © Photo: Francesco Galli

The body and its relationship to others in art

Among the national pavilions that attract our attention are, uncontestably, Germany, represented by Golden Lion winner, Anne Imhof, a multidisciplinary artist renowned for her striking performances. A. Imhof present Faust, a long performance (varying between an hour and a half and two hours) played daily by the performers who scatter through the whole zone enacting a pre-established script and scenario. The performers, both male and female, take over all the available space, going so far as to slip under the raised glass floor that spans the pavilion. The intensity of the music and the eye contact amongst the performers or between the performers and the members of the public around them, bestow a deep theatricalness on the piece and make for a high emotional load. The scenario creates a certain discomfort that nothing can seem to appease. The public, intrigued, is obliged to remain within the walls in order to discover the outcome. The strength of A. Imhof’s show resides in her ability to bring the spectators to thing about the prevailing unease that is inherent to today’s society. With this performance, she seems to wish to insist on our sometimes-difficult relationship to others. The performance still continues to attract large crowds to the German pavilion.

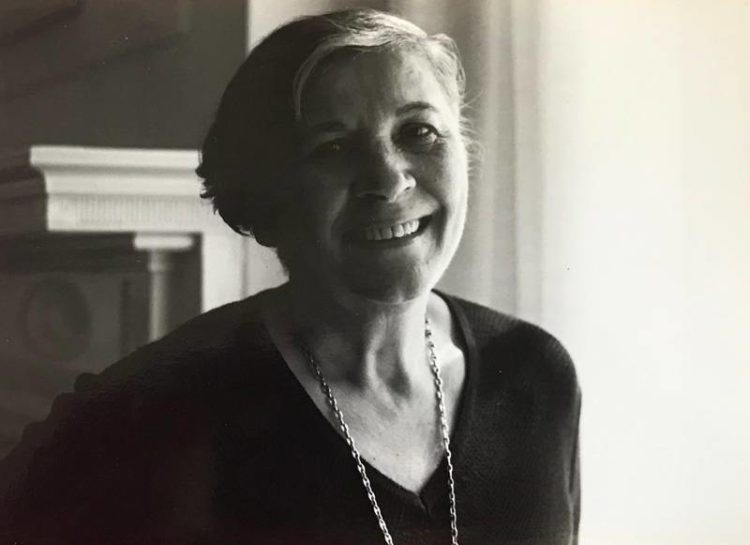

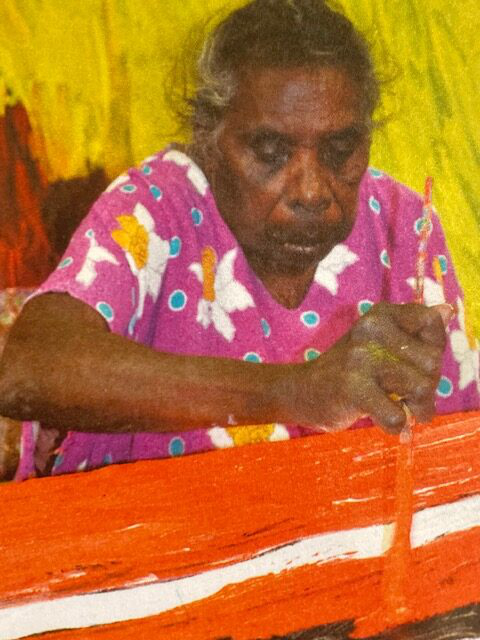

The My Horizon exhibition by Tracey Moffatt, comprising two series of photographs and two videos, is on show in the Australia pavilion. T. Moffatt previously represented her homeland in 1997. Her main theme is colonisation and the confrontation of the different points of view, between the coloniser and he who is colonised. Large format portraits by T. Moffatt of herself dressed in a maid’s uniform make up the Body Remembers series (2015). The minimalist and poetic scenarios give rise to pictures that are underpinned by often-melancholic narrative. They also sometimes show the character’s face turned away or lost in the vastness of the settings – which can be either intimate or barren. The photographs oscillate between the past and present, between projection and memory. They attest to a certain memory of the body and resilience of those who served the colonisers. The images from the Passage series, with their cinematographic and heroic style, bring us more characters of a more contemporary nature. The video called Vigil (2015), projected on the outer wall of the pavilion, is certainly the most striking element of the exhibition. It juxtaposes modified and recolored images of boats full of refugees and portraits of Hollywood stars looking horrified. Moffatt shows to what extent human misery is manipulated for the purpose of large-scale use of its images in public media.

Maha Malluh, Food for Thought “Amma Baad”, 2016, audio tapes, thirty wood bread baking trays, 272.5 x 636 x 8.5 cm, Courtesy Venice Biennale, © Photo: Andrea Avezzù

Maha Malluh, Food for Thought “Amma Baad”, 2016, audio tapes, thirty wood bread baking trays, 272.5 x 636 x 8.5 cm, Courtesy Venice Biennale, © Photo: Andrea Avezzù

Women and political issues

The different sections of the main Arsenale exhibition give room to works by several female artists, particularly in the Dionysian pavilion, that are largely dedicated to women’s bodies. Although the origin of this name may sound paternalistic – why not address bodies, including those of men, transsexuals and LGBTs? –, the section brings together all sorts of political artistic initiatives.

Among the works that attract attention, is a wall-mounted installation by the Saudi artist Maha Malluh (the first Saudi woman to participate in the exhibition in 2016). The monumental mosaic, Food for Thought “Amma Baad”, gathers together in its coloured grooves audiocassettes whose content concerns rules for behaviour destined for women. These cassettes are spread over baking trays, an object which brings to mind a typically feminine task, in such as way as to reproduce the Arabic words that represent each of the concepts rejected in Saudi Arabia. Words such as “fitna” (temptation), “haram” (forbidden according to the Koran) and “jihad” (combat). The artist thus deals with censorship in an efficient, minimalist, visually aesthetically pleasing.

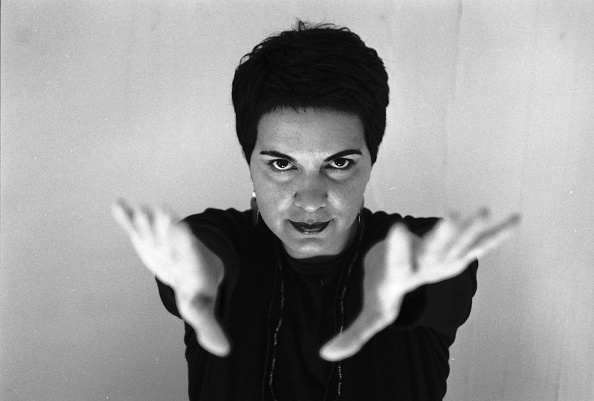

Huguette Caland, Various works, 1971-1995, mixed material, Courtesy Venice Biennale, © Photo: Italo Rondinella

Huguette Caland, Various works, 1971-1995, mixed material, Courtesy Venice Biennale, © Photo: Italo Rondinella

Finally, a special place is reserved for the hanging of several drawings and display of several sculptures by the Lebanese artist Huguette Caland, dating from 1971 to 1993. The works gathered together here represent female genitalia, or as regards the sculptures, people seen in all different positions with their genitalia on show. The delicate outlines of the positions suggested by the artist are a far cry from those that constitute the norm for painting in the history of art or even pornography, destined for male heterosexuals. Here, the female genitalia are represented with an appearance free of any tendency towards idealisation.

Thus the works presented in this section rarely fall into cliché – less than the classification of the subsections of the exhibition. Thankfully, C. Macel seems to pay particular attention to the works selected and their presentation along a circuit that is specially designed to highlight the specific contribution of each piece. It also seems important to underline the impact of several major works on this exhibition, in particular the colourful and sensitive drawings of Kiki Smith, the monumental sculptures of Phyllida Barlow (Great-Britain pavilion) and the political reading by Grisha Bruskin (Russia pavilion) whose installations and light projections generate curiosity among spectators. The revised version of Western history that she proposes – from a political, social, philosophical and religious viewpoint – is materialised in a scenario that is as original as it is pertinent. Right now, there’s everything you need to be able to celebrate the art of women to art in the heart of the Serenissima!