Review

Exhibitions view with Interrogations sur l’art, 1974-1975, acrylic, stencil letter and colored pencil on cotton canvas, video recording, 280 x 200 cm for the canvas, collection Musée national d’Art moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou, © Rights reserved

It is not insignificant that the work of Lea Lublin (1929-1999) is exhibited in Seville, not far from Virgins emblematic of the Spanish baroque – Virgen de las Cuevas (1655), by Francisco de Zurbarán, and Virgen de la Servilleta (1668-1669), by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.1

Lea Lublin, Voir clair. La Joconde aux essuie-glaces, 1965, motor, acrylic, crystal, ribbon and paper on canvas and pressed cardboard, wood, wipers and pear, 67 x 49 cm, collection Nicolas Lublin, © Rights reserved

Neither is it inconsequential that her works, which deconstruct the structures of temporal domination or mind control – colonial, imperialist, paternalist – are exhibited in the very city that systematised the discovery and exploitation of the New World, and notably of Argentina, her native country. The Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, where the artist’s retrospective is held, is itself emblematic of this history, as a former Carthusian convent and as a factory that produced ceramics destined for South America. It is full of statues of Christopher Columbus and nuns in prayer, crosses and coats-of-arms, all of which confer a tumultuous memory to its quiet walls. Since 1995, the building has been primarily dedicated to contemporary art. Women artists are particularly visible here, thanks to the commitment made in 2010 by Juan Antonio Álvarez Reyes, its director, to ensure perfect gender equality in both acquisitions and programming. Thanks to this policy, the institution owns important artworks by VALIE EXPORT, by the Guerrilla Girls (bravely installed next to Yves Klein’s 1960 Anthropométries), by Dora García, Ana Mendieta, Louise Bourgeois, Rebecca Horn, and Cristina Lucas, among others.

Juan Vicente Aliaga, a professor in the fine arts faculty of the Polytechnic University of Valencia and curator of the exhibition, presents around forty works by L. Lublin in the cloister, whose dates range from 1965, the year she abandoned easel painting, to 1999, the year of her death.2 The visit rejects a chronological approach so as to better emphasise the various directions of the artist’s thought: her call for vigilance and her calls to action, inspired by some of the linguistic and psychoanalytical theories of the time; her skilful questioning of images, which takes the form of erasure, destruction, hybridization, penetration, or proliferation; her commitment to feminism; her imaginary connection to Marcel Duchamp; and her connection with the Argentinian political and cultural context. The immaculate white walls subtly accentuate the aesthetic of the artist’s work.

Lea Lublin, La Bouteille perdue de Marcel Duchamp, 1991, 6 light boxes and wooden reels, 130 x 89 x 15 cm, collection Nicolas Lublin, © Rights reserved

Lea Lublin, R.S.I, Dürer, del Sarto, Parmigianino, 1983, acrylic, C-print, postcards and ink on canvas and wood, 350 x 600 cm, © Rights reserved

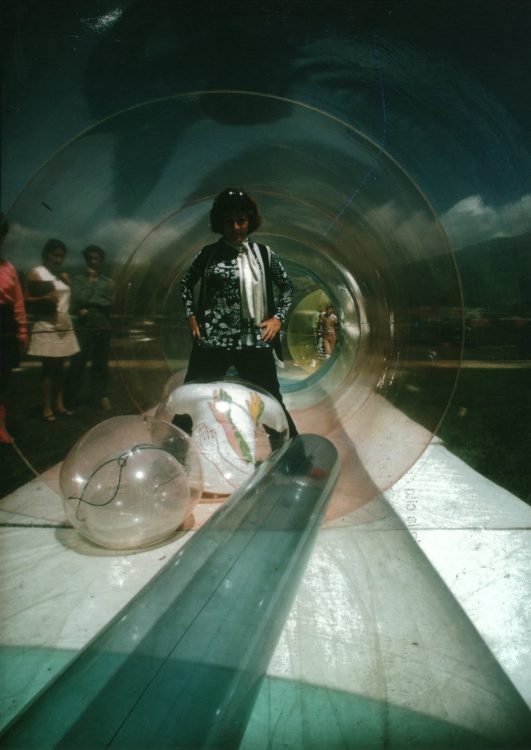

The most “retinal” artworks inaugurate the visit: from the very first work L’Œil alerte [The Alert Eye] (1991) to the explosion of colour in Désirs des peintres [Painters’ Desires] (1983). This series underlines the extent to which, although she is a conceptual artist, L. Lublin has never relinquished the sensuality of form and colour. Pénétration d’images (1974), shown for the very first time since its acquisition in 2017 by the Musée national d’art moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou, invites visitors to become the actors of their artistic experience by daring to traverse a screen on which are projected photographs of emblematic paintings from the history of art – works by Matisse, Picasso, Mondrian, among others, thus find themselves all in a row.

The second part of this retrospective focuses on the artist’s performances and draws together essential documents that constitute all manner of evocative fragments of bygone events. Illuminating comparisons are undertaken: a booklet presents the detail of the date of Saturday 11 March 1978, bringing in for Dissolution dans l’eau. Pont Marie. 17 heures, alongside L. Lublin, Françoise Janicot, Elisa Tan, Claude Torey, and Nil Yalter, or the banner of Interrogations sur l’art [Questions About Art] (1974), with participants’ videos and photographs. These associations help to ‘mentally’ reactivate the actions, to restore their power of conviction. Other actions, particularly those undertaken in South America, are evoked more discreetly. A few additional pieces of information concerning the Argentinian context of the Torcuato di Tella Institute, the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (where Flor de Ducha [Flower-Shower] was shown in 1970), or explanations concerning political shifts during this period would perhaps have given greater focus to the elements exhibited. Furthermore, wouldn’t it have been preferable for Culture: dedans/dehors le musée [Culture: Inside/Outside the Museum] (1971) to be visually present, given that it is mentioned several times in the texts? Both the absences and the selection itself remind us of the infinite diversity of L. Lublin’s multifaceted and political practice, which merits ongoing rediscovery.

Lea Lublin, from 27 April to 16 September 2018, at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (Seville, Spain).

These two paintings are presented at the Museo de Bellas Artes de Seville. The first was initially commissioned by Francisco de Zurbarán for the Santa María de las Cuevas monastery, where the exhibition was held.

2

It is the largest exhibition dedicated to the artist since Lea Lublin – Retrospective, held from 25 June to 13 September 2015 at the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau in Munich (Germany).

Hélène Gheysens, "Lea Lublin: Radical Iconoclast." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/lea-lublin-iconoclaste-radicale/. Accessed 14 July 2025