Research

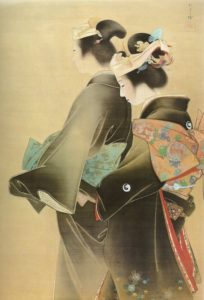

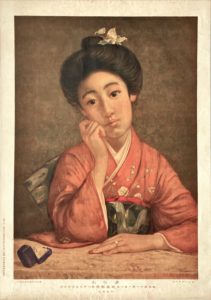

Ikeda Shōen, Monomōde [Going to the Temple], 1908, and Haru no hi [Spring Day], 1908, color on silk, Fukuda Art Museum, Saga Arashiyama, Kyoto.

The Advent of Women Bijinga Painters

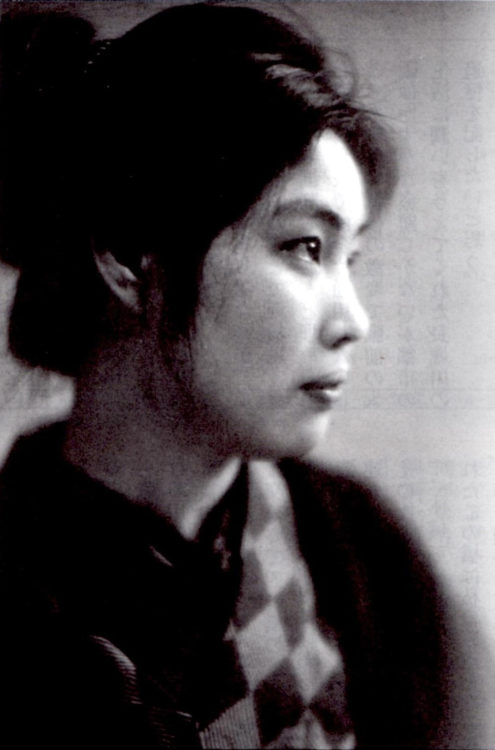

The Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting (Kyōtofu Gagakkō; now the Kyoto City University of Arts) was founded in 1880 – prior to the opening of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō, now the Tokyo University of the Arts) – marking the start of painting education, including Western-style painting, in Japan. Initially, women were allowed entrance, and Uemura Shōen (1875–1949) – who would later become the most famous painter of bijinga (pictures of beautiful women) – entered the programme in 1887 at the age of twelve to study under the well-known artist Suzuki Shōnen (1848–1918). When Suzuki Shōnen quit the following year, she enrolled in his private painting school and trained alongside other older men. Though Uemura Shōen had been born into a family that had no affiliation with any artist, she was able to enrol in art school just before the establishment of sex-segregated education, and this secured her an advantageous learning environment. According to Seibishō (Tokyo: Rikugō Shōin, 1943), an essay penned in her later years, she enjoyed drawing figures from an early age, and her first models were ukiyo-e prints sold at picture book shops; illustrated books, warrior prints (musha-e) and actor prints (yakusha-e) displayed at night stalls; and books illustrated by Hokusai borrowed from lending libraries. It has been pointed out that many of Uemura Shōen’s later bijinga works incorporate themes and compositional elements from ukiyo-e. In primary school, she sketched nothing but pictures of women, and she grew dissatisfied with her art school education, where – beginning with single stems of flowers, such as camelias and magnolias –she progressed through the techniques of drawing birds, landscapes, trees, and rocks. Following art school, she continued her own research, attending exhibitions of old paintings and going to the Imperial Museum (Teikoku Hakubutsukan; later the Imperial Household Museum [Teishitsu Hakubutsukan]), which opened in Kyoto in 1897.

Like Shōhin Noguchi (1847–1917), Uemura Shōen gained a toehold on success through exhibitions of her work. In 1893, a work of hers that was exhibited at the Third National Industrial Exhibition (Naikoku Kangyō Hakurankai) was purchased by Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (Arthur William Patrick Albert, 1850–1942), who was then visiting Japan. The purchase was reported in the newspapers, leading to a rise in Uemura’s popularity. As a result, she was commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce to show her work in the Women’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which in turn boosted her confidence as an artist. From her first appearance in 1907 at the inaugural Monbushō Bijustu Tenrankai (hereafter referred to as the Bunten Exhibition), she continued to win awards for her depictions of young women, and she became an important artist for the Teikoku Bijutsuin Tenrankai (hereafter referred to as the Teiten Exhibition) that succeeded it as well. Ultimately, her seniority over the increasing number of women artists in the field, as well as her having been active early in life, made her quite an exceptional figure. Given her aspiration to become a painter, Uemura Shōen eschewed dressing like a woman. Though she was a single mother, household chores and childrearing were carried out by her own mother. Indeed, her manner of working was much like that of a male painter.

By contrast, Ikeda Shōen (née Sakakibara, 1888–1917), who was thirteen years younger than Uemura Shōen, was born to an affluent Tokyo family and belonged to the generation who received a girls’ education at a girls’ school. This is a significant difference. Ikeda Shōen’s father was a businessman, and her mother learned the Western-style yōga painting as a hobby. In her essay, “Watashi no kyō aru wa mataku shi no tamamono (What I have today is utterly the gift of my teacher)” (Fujin Gahō 51, January 1911), she notes that in 1901, she studied under Mizuno Toshikata (1866–1908) but “had to practice koto, tea ceremony, and silk-flower arrangement” in addition to this study. In the early modern period, such arts were primarily practised by men. In S. Ikeda’s day, however, they were considered exemplary skills that young women of good families ought to acquire. Ikeda enjoyed painting, stating, “In primary school, I would look at the illustrations in magazines and newspapers and sometimes copy them”. Though she was of a younger generation than Uemura Shōen, she still attempted to draw figures by copying from printed magazine frontispieces and newspaper illustrations. Given that her father was a disciple of the businessman Fukuzawa Yukichi (1834–1901), if they subscribed to the latter’s daily, Jiji Shimpō, she may have seen the lithographs of original drawings by Masako Okamura (1858–1936), which were distributed as special editions.

Ikeda preferred studying with Mizuno, despite her mother’s interest in yōga painting, because of his figural work. Kaburagi Kiyokata (1878–1972), a fellow student, and her future husband Ikeda Terukata (1883–1921) both also became bijinga painters. Ikeda Shōen, too, won a prize for her diptych Monomōde [On a Prayer Visit, 1908] at the First Bunten Exhibition, becoming a popular artist herself. Writing in his feature article, “Miss Shōen Sakakibara, a Talented Female Painter,” which was published in Fujin Gahō 9 (March 1908), reporter Bushō Sawada writes, “When looking for the youngest and yet the most outstanding individual, one may look no further than Miss Shōen Sakakibara.” Ikeda Shōen herself once commented, “My teacher always told me, ‘Paint people, not dolls. Spirit and elegance are imperative to painting and must not be forgotten’.” In this, she was encouraged to make a deeper exploration of the subject’s interior life. Ikeda’s fame through exhibitions was on par with that of her predecessor Uemura.

Ikeda Shōen, Monomōde [Going to the Temple], 1908, and Haru no hi [Spring Day], 1908, color on silk, Fukuda Art Museum, Saga Arashiyama, Kyoto.

Another bijinga artist, Kurihara Gyokuyō (1883–1922) is also said to have copied the frontispieces of novels borrowed from lending libraries.1 During that period, artists such as Takeuchi Keishū (1861–1943), Tomioka Eisen (1864–1905), and the aforementioned Mizuno Toshikata were popular illustrators, although Kurihara may have been looking at older works. In 1907 she enrolled at the Private Women’s School of Fine Arts (Joshi Bijutsu Gakkō, now the Joshibi University of Art and Design), but her teachers were uncomfortable with figure painting, and the school itself lacked reference materials, so she studied figure painting by copying old masterpieces on display in museums and at the library. She was particularly enamoured with drawing children.

From this, we can see that the women who became famous bijinga artists used popular publications as copybooks from a young age, instinctively gravitating towards the depiction of women and children. This suggests that the division of gender roles in the home had already permeated these women’s daily lives. Furthermore, because they were not born into established artist families, and therefore did not learn the painting hierarchy of the early Meiji period – which held that ukiyo-e and illustrations were “common” in comparison with works of the Kanō and Nanga schools – they were able to paint freely, and that was an important factor in their development. In later days, Uemura disliked having her work compared with the ukiyo-e genre, and Mizuno’s instruction to Ikeda – that “spirit and elegance are imperative to painting” – may also have been due to his own concern, as a descendant of the ukiyo-e lineage, that figure painting would be seen as “common”.

The expression of beauty

Uemura Shōen et Ikeda Shōen

It was around the time of The Jinsei no hana [The Bloom of life] (1899; Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art) that Uemura established her style of large-scale depicting young women against a nearly empty background. The bloom of life depicts a young woman clad in wedding attire and looking down as she is led to her future husband’s house by her mother on the day of her wedding. Given that several similar works by Uemura remain extant, we may surmise that this work was well received by the public. The originator of this style of depicting only womenin a picture was Noguchi Shōhin, who was then living in Kyoto. Kōno Bairei (1844–1895) and Mori Kansai (1814–1894), who trained numerous Nihonga painters in Kyoto, painted various geisha, but what is new about Uemura’s work is that the subject is not a geisha, but rather a young woman from an ordinary family. Moreover, the young woman who leaves one house to marry into another is a subject in line with the system of patriarchy promulgated by the Meiji government. If the woman who views the painting is young, she can empathise with the bride; if she is older, she can identify with the mother. In painting works that garnered not just the support of men but that of women as well, women artists like Uemura steadily gained popularity.

Though Uemura reminisced about her study of ukiyo-e and traditional Japanese paintings, this would not have been enough to enable her to create three-dimensional figures. Upon returning to Japan following a period studying in Europe, from 1900–1901, Nihonga painter Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942) hired models and worked on figure painting together with a number of his students. Uemura studied under Takeuchi, and while the details of that time are largely unknown, it is said that she copied designs while in his studio. Perhaps she also learned something from the figure studies that date he produced after his return to Japan.

The left panel of Ikeda Shōen’s Haru no Hi [Spring day, 1908] depicts a young woman enjoying a spring day while knitting and looking after her little sister. Knitting was a newer handicraft that had been introduced in the modern period. It is a subject consistent with the gender roles that women of the time were expected to play. The three-dimensionality of the figures can easily be seen in the rendering of the young woman’s fingers and suggests that Ikeda learned figural representation from Western paintings. As we have already seen, Ikeda belonged to the generation that also had the opportunity to view lithographs of figure paintings. Additionally, yōga painters such as Okada Saburōsuke (1869–1939), who studied academic painting in France, began creating works that depicted women in outdoor settings, and S. Ikeda may have also taken inspiration from these paintings. Okada applied the technique of idealising the human form to Japanese bodies, showcasing young women clad in sumptuous kimonos. These works were circulated via newspaper special editions and magazine illustrations. Given that he was also responsible for several frontispieces for women’s magazines, we may surmise that his work was also popular with women. S. Okada served concurrently as professor at both the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and the Private Women’s School of Fine Arts, and many Nihonga painters would likely have referenced his portraits of women.

Okada Saburōsuke, Yu biwa [Ring], 1908, lithograph, supplement to the Jiji Shimpō. Private Collection.

The Bunten Exhibition

The Bunten Exhibition attracted large crowds every time it was held. Furthermore, since it was possible to purchase exhibited works at the venue, collectors would flock to the show on its opening day in order to compete for the right to buy. The Sixth Bunten Exhibition, held in 1912, saw more than 160,000 visitors over the course of its 36-day run, and the Eleventh Bunten Exhibition, held in 1917, saw no less than 240,000 visitors over the same period. S. Ikeda achieved the most sales, followed by other women of the bijinga art movement, including Uemura Shōen, Kawasaki Rankō (1882–1918), Kurihara Gyokuyō, and Shima Seien (1892–1970).2 Of the male artists who exhibited, Ikeda Shōen‘s husband, Terukata, and fellow student, Kaburaki Kiyokata, were popular.

Uemura Shōen, Mai shitaku [Preparing to dance], color on silk, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

The January 1915 issue of Nippon Bijutsu (vol. 17, no. 3) was published as a “women artists issue (keishū sakka gō)” and featured images of works by popular women artists from the Bunten Exhibition on the frontispiece. Each artist had undergone different training, but all of the women they depict, beginning with Uemura’s Mai Shitaku [Preparing to Dance (Mai shitake)] and G. Kurihara’s Uwasa no Nushi [The Subject of a Rumour], feature plump faces with heavy, somewhat drooping eyebrows; fairly wide-set eyes; thick eyelashes and large, dark eyes. From this we may deduce that there was a common “type”, as it were, of woman that was depicted by women artists. This may have been due to this style of representation preferred by the audience that came to the Bunten Exhibition. In his article “The Value of Women Artists (Joryū sakka no kachi)”, published as part of the “Women Artists” issue, Wakatsuki Matsunosuke describes how, with the rise of nationalism following the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, people began to seek out extravagant things, noting that “it was women artists who took advantage of this opportunity to paint beautiful women and captivate viewers with their use of rich, luminous colours”.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 led to a booming war economy and works depicting happy young women and children grew in popularity. In an article for Bijutsu Shimpō, Sakai Saisui noted that, “The most appropriate subject matter for a woman artist is women, particularly women engaged in domestic activities”.3

At the Ninth Bunten Exhibition in 1915, all the paintings of beautiful women were displayed in a single space, the “Bijinga Room”, and attracted a large number of visitors. In gathering these paintings together in one place, the stereotyping of feminine features was easily criticised.4 These criticisms were particularly directed at women artists, and in newspaper and magazine articles the arguments took on a tone of men airing their grievances against popular women artists. The flourishing of the bijinga genre and the popularisation of the Bunten Exhibition coincided. With the support of the public, women artists seemed to take pride in their prosperity, but in an exhibition setting, where male jurists and critics were in control, they were subject to those men’s will. For the Tenth Bunten Exhibition, it was reported that women artists from the Kansai region were rejected. At the Twelfth Bunten Exhibition in 1918, Uemura Shōen exhibited Flame (Hono’o), which depicts a vengeful spirit from a Noh play and represents a complete change from her style up to that point. Meanwhile the death of Ikeda in 1917, and Kawasaki Rankō died in 1918, followed by Kurihara Hyokuyō in 1922 durably modified the landscape of art.

The Teiten Exhibition

The Teiten Exhibition was established in 1919, and initially, there were few bijinga paintings. Starting around 1925, bijinga works began to be prominently exhibited. Kaburagi Kiyokata won the Imperial Fine Arts Academy award for his painting Tsukiji Akashimachi (1927), which in later years became famous as a work of bijinga, but he himself hated that designation, preferring to position it as “social painting” (shakaiga). Kikuchi Keigetsu (1879–1955), a mainstay of the Teiten Exhibition, also objected to his paintings of women being seen as bijinga. Men who had already established their position as artists turned their backs on the bijinga genre, but later iterations of the Teiten Exhibition saw the emergence of a new generation. Among women artists, Seiyō Kakiuchi (1892–1982), who graduated from the Private Women’s School of Fine Arts and was a student of K. Kaburagi’s, was accepted to exhibit her painting Sixteenth Spring(Juroku no haru; collection of the Joshibi University of Art and Design) at the Sixth Teiten Exhibition. It was then printed and distributed as a newspaper calendar in the following year. At the same exhibition, Chigusa Kitani (1895–1947) of Osaka garnered attention for her work The Remnants of the Eyebrows (Mayu no nagori) in which the skin of a voluptuous woman can clearly be seen through her kimono.

As old age approached, Uemura Shōen became increasingly devoted to Noh theatre and its subjects. Moreover, in depicting the manners and customs of the Meiji period – which had already become a thing of a past – she created idealised images of women that were far removed from reality. Uemura was frequently asked to exhibit her works in overseas Japanese art exhibitions, likely because this idealised female image was expected to play a role in presenting an image of Japanese women to foreign audiences. Furthermore, Mother and Child (Boshi), which was exhibited at the Teiten Exhibition in 1934, and Dance Performed in a Noh Play (Jo no mai), which was included in the 1936 Bunten Shōtaiten Exhibition, were both purchased by the government. During the Chinese-Japanese war, as more men found themselves on the battlefield and fatherless homes increased, Uemura’s own family situation – raised by a single mother to become a single mother herself – came to be viewed more positively. In 1941 she became a member of the Imperial Art Academy (Teikoku Geijustsuin); in 1944, she became an Imperial Household Artist (Teishitsu gigei’in). It was a career that rivalled, and perhaps even surpassed, that of her male contemporaries.

The female artists who painted these fragile and ephemeral women were, in fact, busy making a living as independent artists. Their popularity led to young women seeking out apprenticeships with them, and many of these artists taught painting at private schools established in their homes. In the case of S. Ikeda, it was possible to take both male and female students due to the fact that she ran her private painting school with her husband, but most of the schools run by women artists took mainly female students. C. Kitani also studied under S. Ikeda for a time, and following her marriage, she formed the Yachigusa-kai, a private painting school in Osaka, which was active with a number of women.5 Essentially, women attended this school as part of their premarital lessons, but in 1925, C. Kitani reorganised the school into a research facility and began holding exhibitions. She also organised her own exhibitions with other women painters in Osaka.

In the case of G. Kurihara, who was single, running a private painting school was a crucial source of steady income. The March 1918 issue of Shukujo Gahō (Women’s Illustrated) reports on a lively New Year’s party that was held by one of G. Kurihara’s students. In looking at the pictures of the students lined up with their works, we note that the latter are all quite similar and resemble copies of G. Kurihara’s own work. It is clear that, rather than making a show of creativity, these women adhered to their teacher’s style like a group of fans. G. Kurihara created numerous frontispiece illustrations for women’s magazines. She also formed a study group in 1920, the Getsuyō-kai – mainly with other women artists who had also graduated from the Private Women’s School of Fine Arts– and held exhibitions.

Young women, longing for the idealised beauties painted by women artists, flocked to private painting schools and, in reproducing this unrealistic image of women, indulged in the bijinga paintings of a women-only world. This was a world closed off from the real world ruled by men. However, this sisterhood-like cooperation supported the livelihood and research activities of countless women artists.

Cet article suit « De l’ère Edo au début du XXème siècle : l’éducation artistique des femmes peintres », publié le 13 octobre 2023.

For more on G. Kurihara, see Kaoru Kojima, “Josei gaka toshite no Kunihara Gyokuyō: ‘Joseisei’o aidentiti toshite (Woman artist Gyokuyō Kurihara: ‘Femininity’ as identity)”, in Kurihara Gyokuyō, ed. Gomi Toshiaki (Nagasaki: Nagasaki Bunkensha, 2018), pp. 228–239.

2

Hanryō Yoshida, Teikoku kaiga hōten: Ichimei, Bunten shuppin hiketsu (A treasury of Japanese paintings: Secrets of solo and Bunten exhibitions) (Tokyo: Teikoku Kaiga Kyōkai, 1918).

3

Josei Nihon gaka Kitani Chigusa: Sono shōgai to sakuhin (The Japanese woman artist Chigusa Kitani: Her life and works) (Ikeda: Ikeda Shiritsu Rekishi Minzoku Shiryōkan, 2002).

4

Sansui Sakai, “Tōto no keishū fūzoku gaka, jō (Accomplished women genre painters of the capital, part 1),” Bijutsu Shimpō 13, no. 6 (April 13, 1914): p. 216

5

On the subject of the “Bijinga Room,” see Noriyuki Nakano, “Bijinga shitsu saikō: Bijinga shitsu no hyōka to hyōgen (A reconsideration of the Bijinga Room: Criticisms and representations of the Bijinga Room), Kindai Gasetsu 27 (2018): pp. 32–53; and Namasa Itō, “Dai-kyū-kai Bunten no mae to ato: ‘Bijinga’ o megute shosō (Before and after the Ninth Bunten Exhibition: Various stages of ‘bijinga’ painting)”, in Kurihara Gyokuyō, ed. Gomi Toshiaki (Nagasaki: Nagasaki Bunkensha, 2018), pp. 256–271.

Kojima Kaoru (児島薫 略歴)

Born in Tokyo. Kojima Kaoru is Professor of Art History at Jissen Women’s University, Japan. She graduated from Faculty of Letters, Tokyo University, and received a Master’s degree from the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, Tokyo University in 1985. She was an assistant curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo from 1987 to 1993. She received a PhD from the University of the Arts, London in 2007. She is the author of, Joseizō ga utsusu Nihon: Awase-kagami no nakano Jigazō (Images of women reflect modern JapanSelf-portrait between dual mirrors) (Tokyo: Burukke, 2019). Other publications include: “The Changing Representation of Women in Modern Japanese Paintings”, in Refracted Modernity: Visual Culture and Identity in Colonial Taiwan, ed. Kikuchi Yuko (Honolulu: Hawaii University Press), pp. 111–132. “The Woman in Kimono: An Ambivalent Image of Modern Japanese Identity”, in Jissen Women’s University, Aesthetics and Art History no. 25 (March 2011): p. 1–15. “Kindai-ka no tame no Josei Hyōshō: Moderu to shite no Shintai”, in Azia Josei no Shintai wa Ikani Egakaretaka: Shikaku hyōsyō to Snso no Kioku, ed. Kitahara Megumi (Tokyo: Seikyusha, 2013). “Pictures of Beautiful Women: A Modern Japanese Genre and its Counterparts in Europe, China, Korea and Vietnam”, Review of Japanese Culture and Society 26 (2014): pp. 50–64. “Joseizō ga shimesu Kindai, Taishū”, in Modern Bijin Tanajō: Okada Sburōsuke to Kindai no Yosooi (exh. cat. Hakone: Pola Museum of Art, 2018).

This article is followed “From the Edo era to the beginning of the 20th century: the artistic education of women painters”, published October 13, 2023.

Kojima Kaoru, "Women Nihonga Painters and Bijinga." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/premieres-femmes-peintres-de-bijinga/. Accessed 14 February 2026