Agnes Martin

Anastas Rhea, Cooke Lynne, J Kelly Karen, et al., Agnes Martin, exh. cat., Dia Art Foundation, New York (2014), New Haven, Yale University Press, 2014

→Morris Frances, Bell Tiffany, Ackermann Marion (ed.), Agnes Martin, exh. cat., Tate Modern, London; Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Wastfalen, Düsseldorf; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, (2015-2016), London/New York, Tate Publishing/ Distributed Art Publishers, 2015

→Schwarz Dieter, Agnes Martin: Writings, Ostfildern-Ruit, Hatje Cantz, 2005

Agnes Martin: Paintings and Drawings, 1974–1990, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, 1991-1992

→Agnes Martin : The Islands, Josef Albers Museum, Bottrop, 14 March–16 May 2004

→Agnes Martin, Tate Modern, London; Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Wastfalen, Düsseldorf; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 2015-2016

American painter.

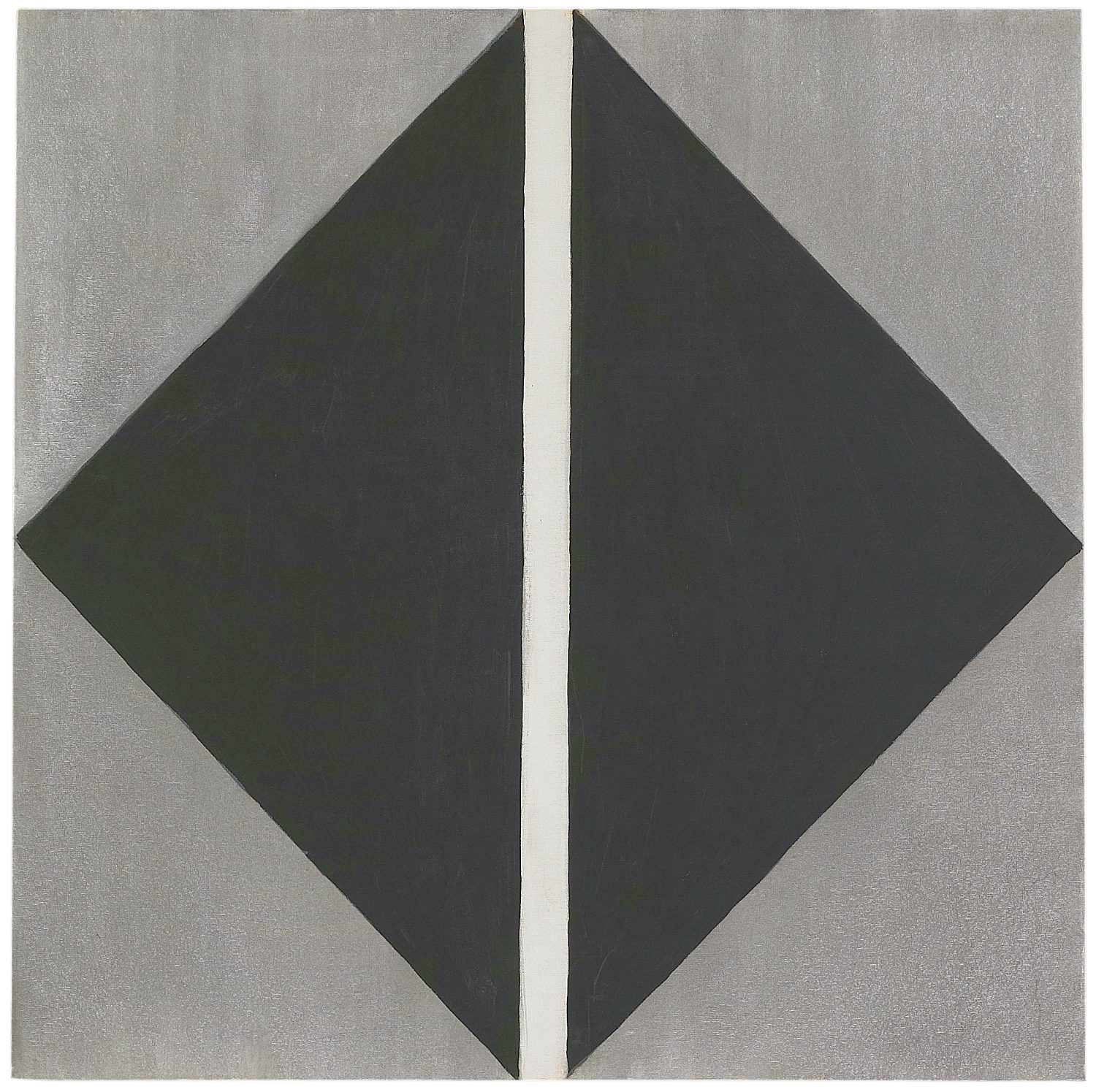

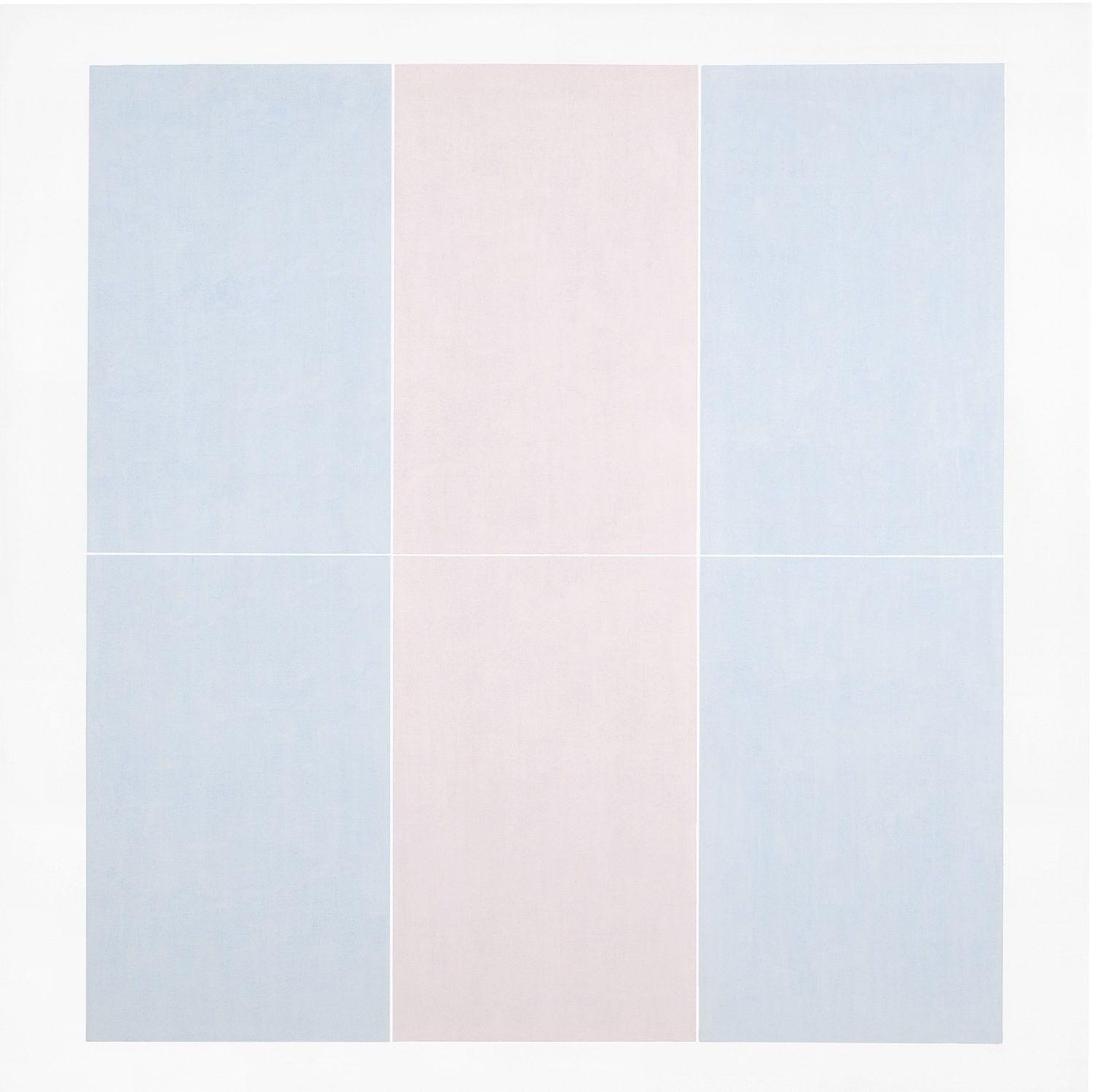

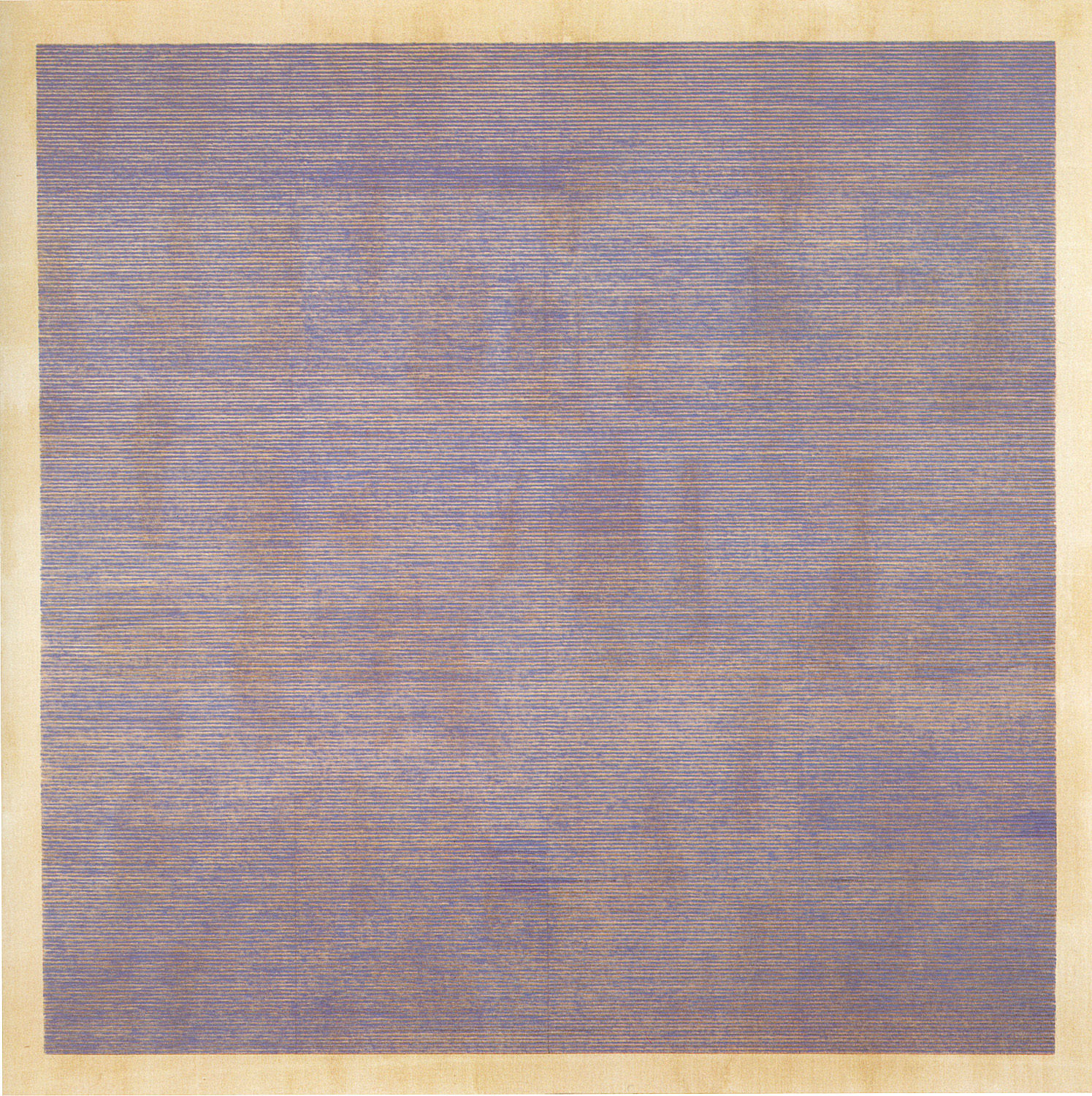

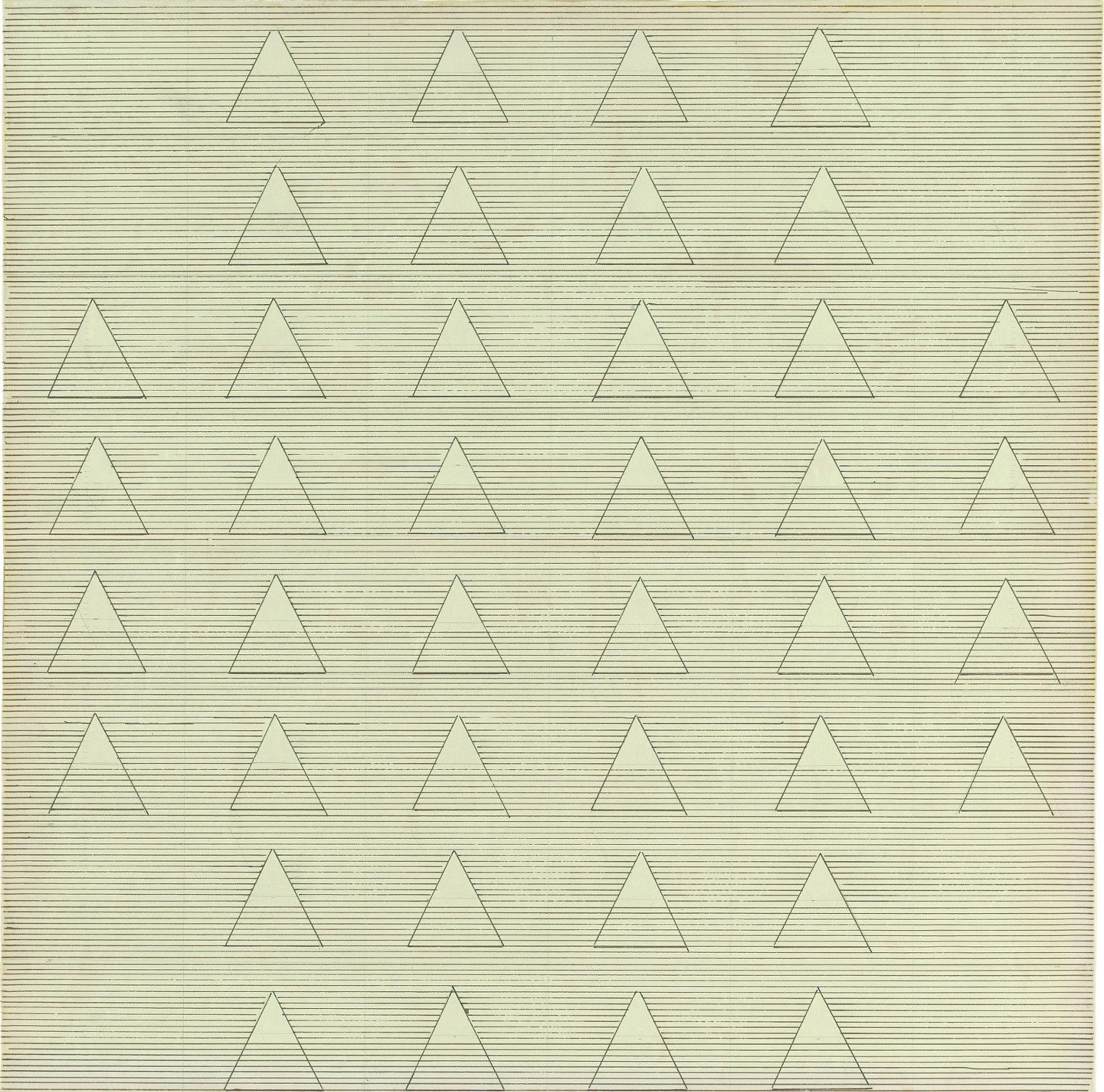

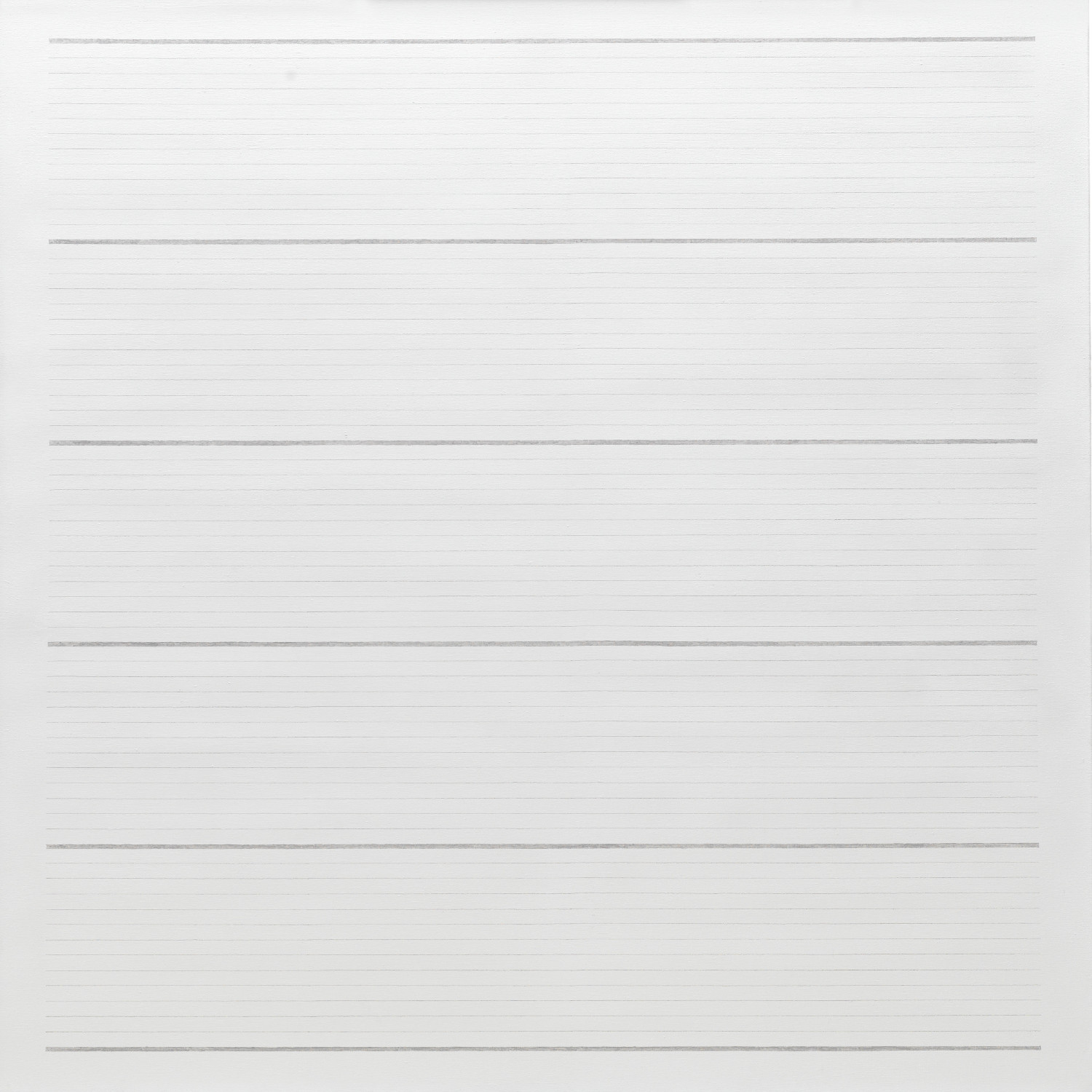

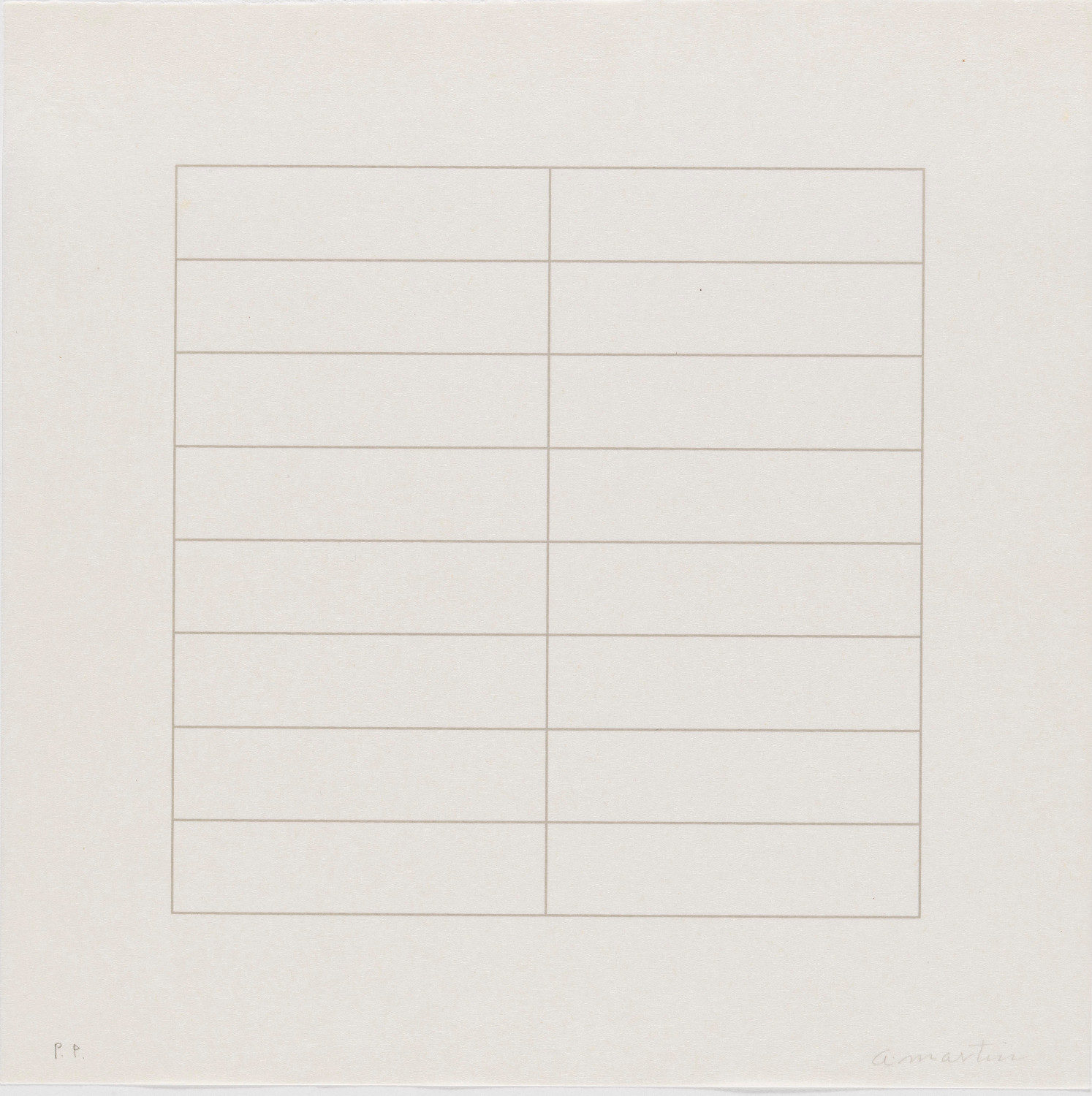

The regularity and sobriety of Agnes Martin’s forms often prompt people to associate this major 20th century figure with the Minimalist movement. Yet she herself reckoned that she was closer to the Abstract Expressionists, her contemporaries, and her first models in painting. Born into a religious family, in 1932, she went to study and then teach in the United States. In New York, she discovered Abstract Expressionism and Zen philosophy, and started to paint. In 1947, she settled in New Mexico, a state whose beauty she much appreciated. The works from that period (which she would later destroy) were inspired by Surrealism. The gallery owner Betty Parsons urged her to return to New York, in 1957, where she met Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Ellsworth Kelly and Jasper Johns. Initially composed of broad horizontal coloured stripes, her painting veered towards a palette of greys and browns. The mid-1960s for her was a period synonymous with a maturity in her painting. She adopted the square format, typical of the 20th century, which she would stay with all her life. Drawing pencil lines by hand, she worked with oil (then acrylic) on unprepared canvases. Contrary to any mechanical vision, an unevenness on the canvas, a trembling of the hand and pressure from the ruler all informed her pictures with intense life and emotion.

Martin considered music to be one of the highest art forms, and her paintings and drawings, which it seems possible to read like musical scores, are sometimes compared with Paul Klee’s oeuvre. Her work, which is the outcome of meditative reflection, aimed at nothing other than reflecting reality. A personal crisis took her back to New Mexico in 1967. She built herself an adobe house and did not paint for seven years. In 1974, she agreed to exhibit again; and she then become a legend. In a state of solitude and concentration, she carried on with her work on the grid with canvases on a human scale, 183 x 183 cm [72 x 72 in.], covered with gesso, a mixture of plaster which absorbs and reflects light. The soft tones of those stripes, horizontal and vertical, call to mind the houses of Native Americans. The lines sometimes stop before the edge of the canvas, producing a floating effect. Her later works have dark grey tones, akin to Chinese painting. As Martin often said in her many writings, it is the aspiration to a certain poetic classicism which seems to have guided her, even if it represents a form of ideal of the mind.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Agnes Martin, TateShots, 2015

Agnes Martin, TateShots, 2015  Agnes Martin at Tate Modern on The Art Channel, 2015

Agnes Martin at Tate Modern on The Art Channel, 2015