Imogen Cunningham

Rule Amy, Imogen Cunningham: Selected Texts and Bibliography, Oxford, Clio Press, 1992

→Lorenz Richard & Weston Edward, Imogen Cunningham, Cologne/London/Paris, Taschen, 2001

→Fuentes Santos Mónica; Fundación Mapfre; Kulturhuset (ed.), Photographs by Imogen Cunningham, exh. cat., Fundación Mapfre, Madrid; Kulturhuset, Stockholm (18 September–20 January 2013; 24 May–8 September 2013), Madrid, Fundación MAPFRE; Alcobendas, TF Editores, 2012

Imogen Cunningham: In Focus, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 3 September 2016–18 June 2017

→Imogen Cunningham, Fundación Mapfre, Madrid; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, 18 September 2012–20 January 2013; 24 May–8 September 2013

→Photographs by Imogen Cunningham, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 24 April 1973–2 July 1973

American photographer.

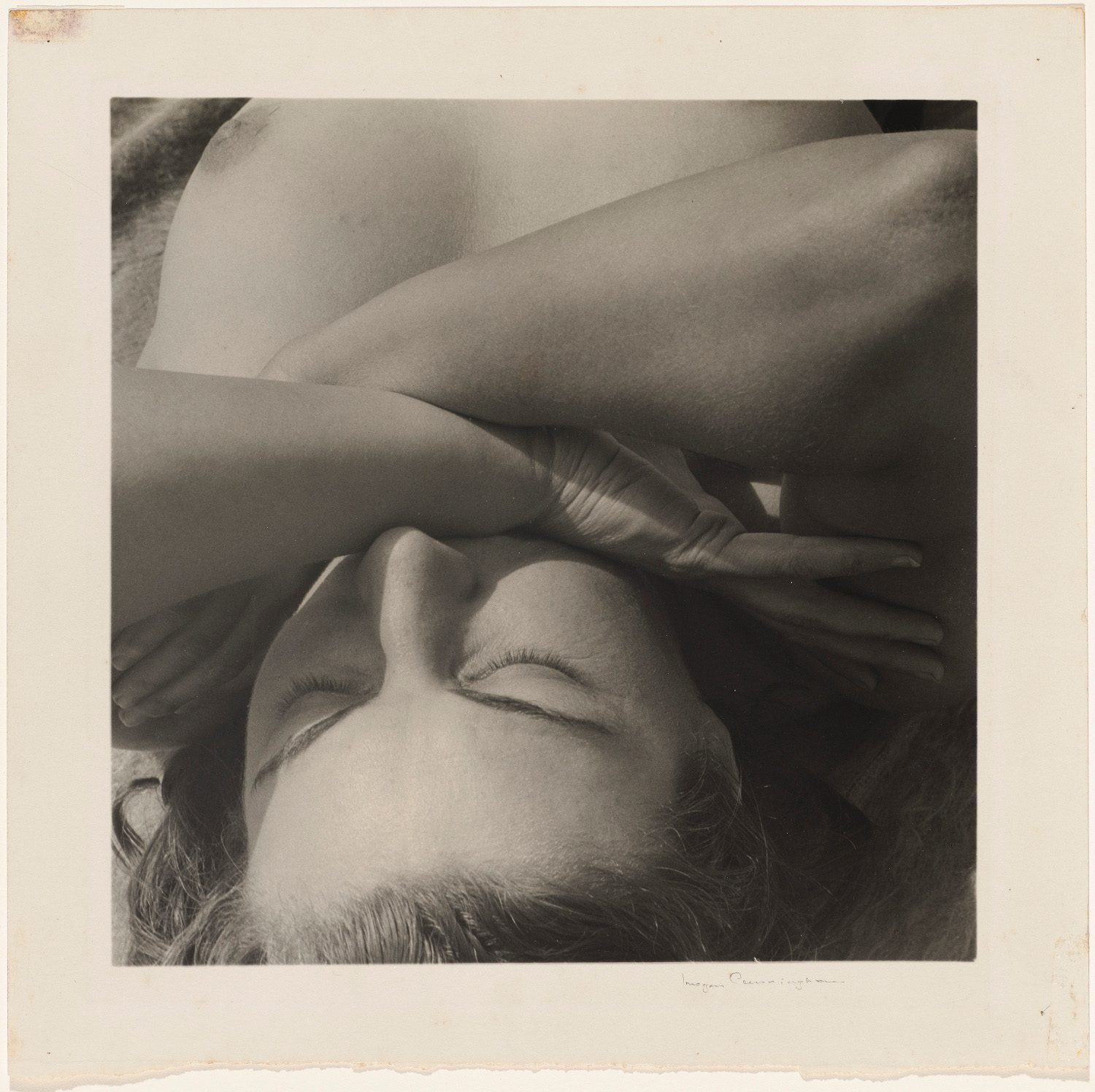

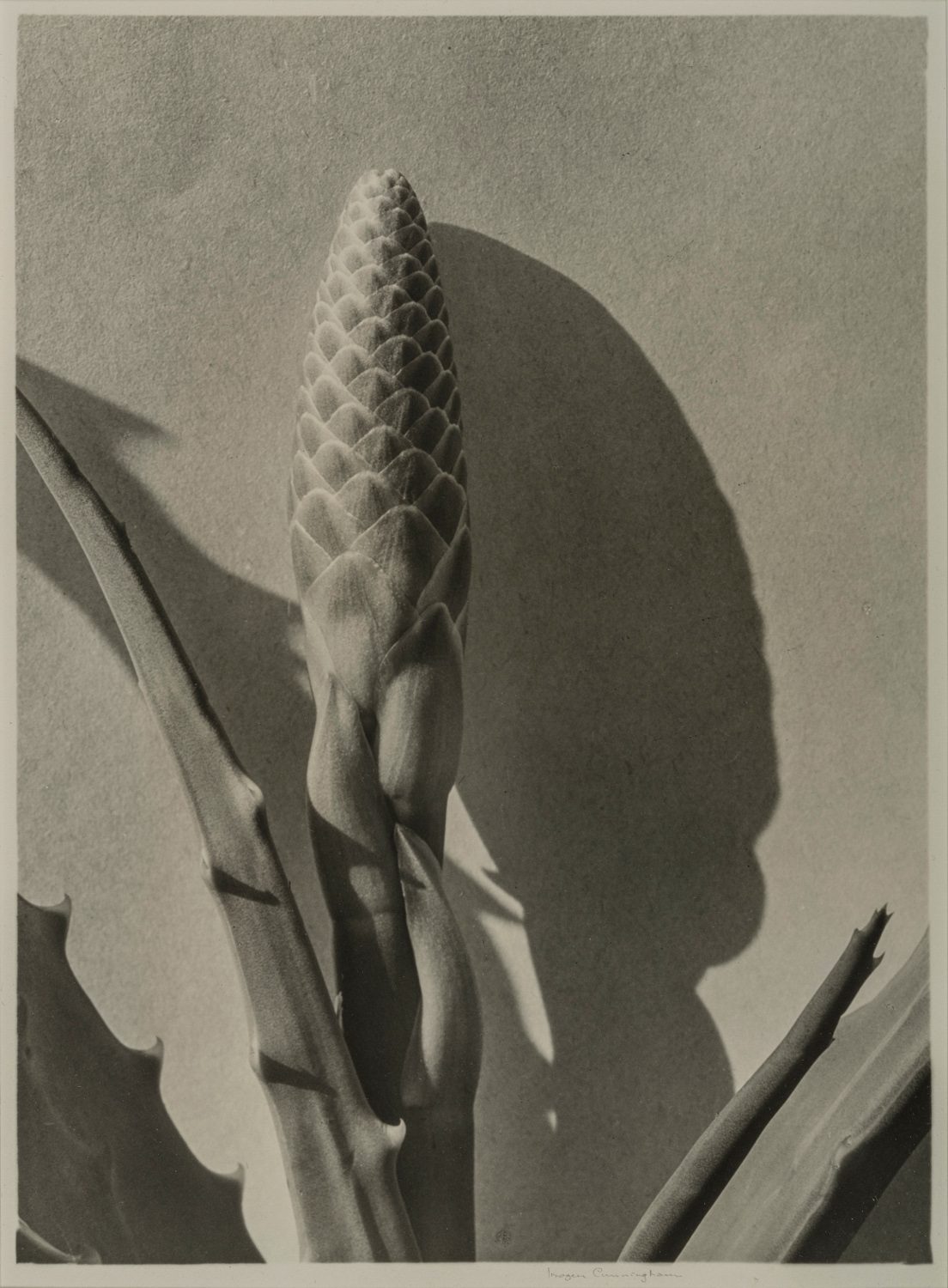

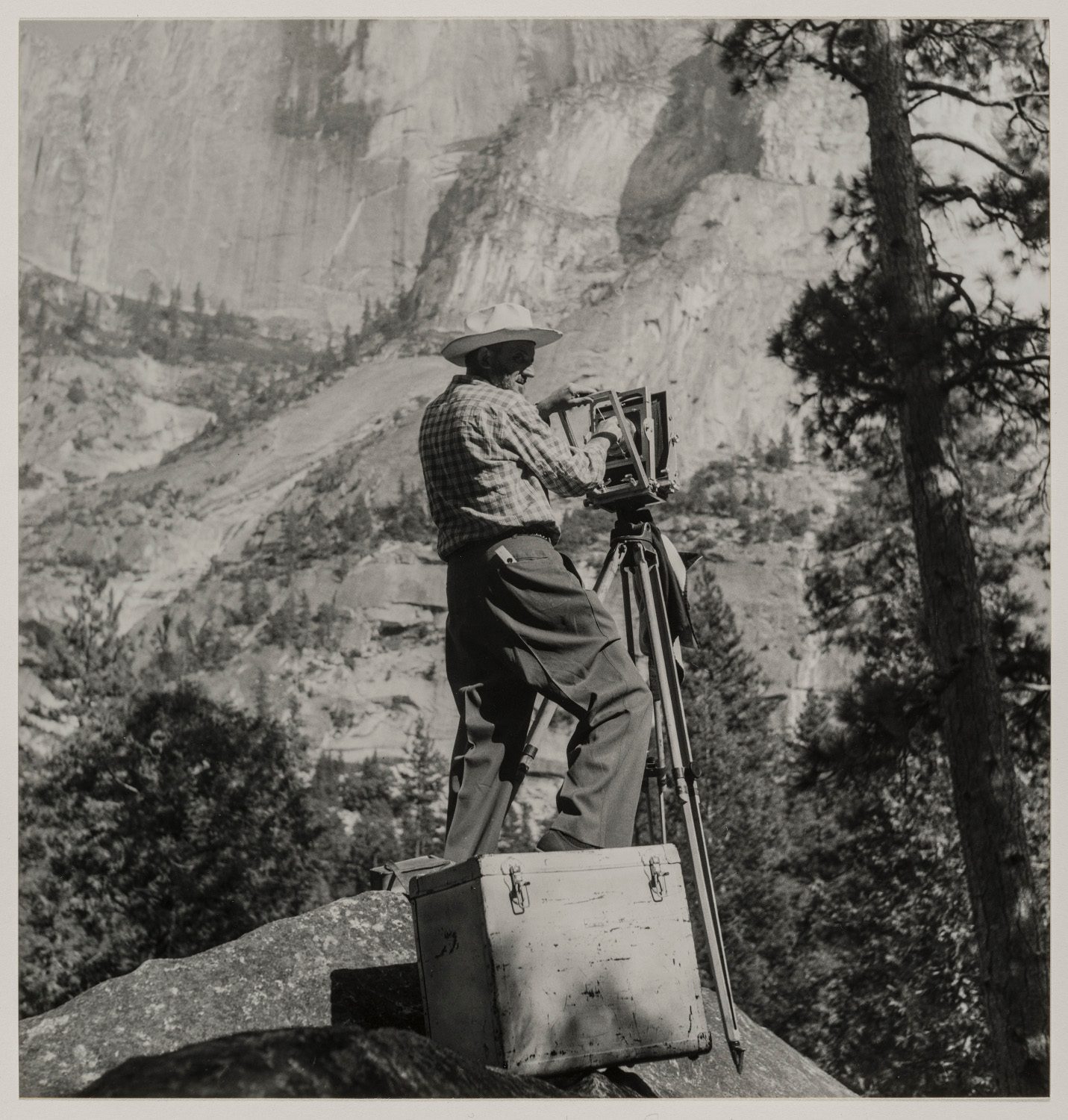

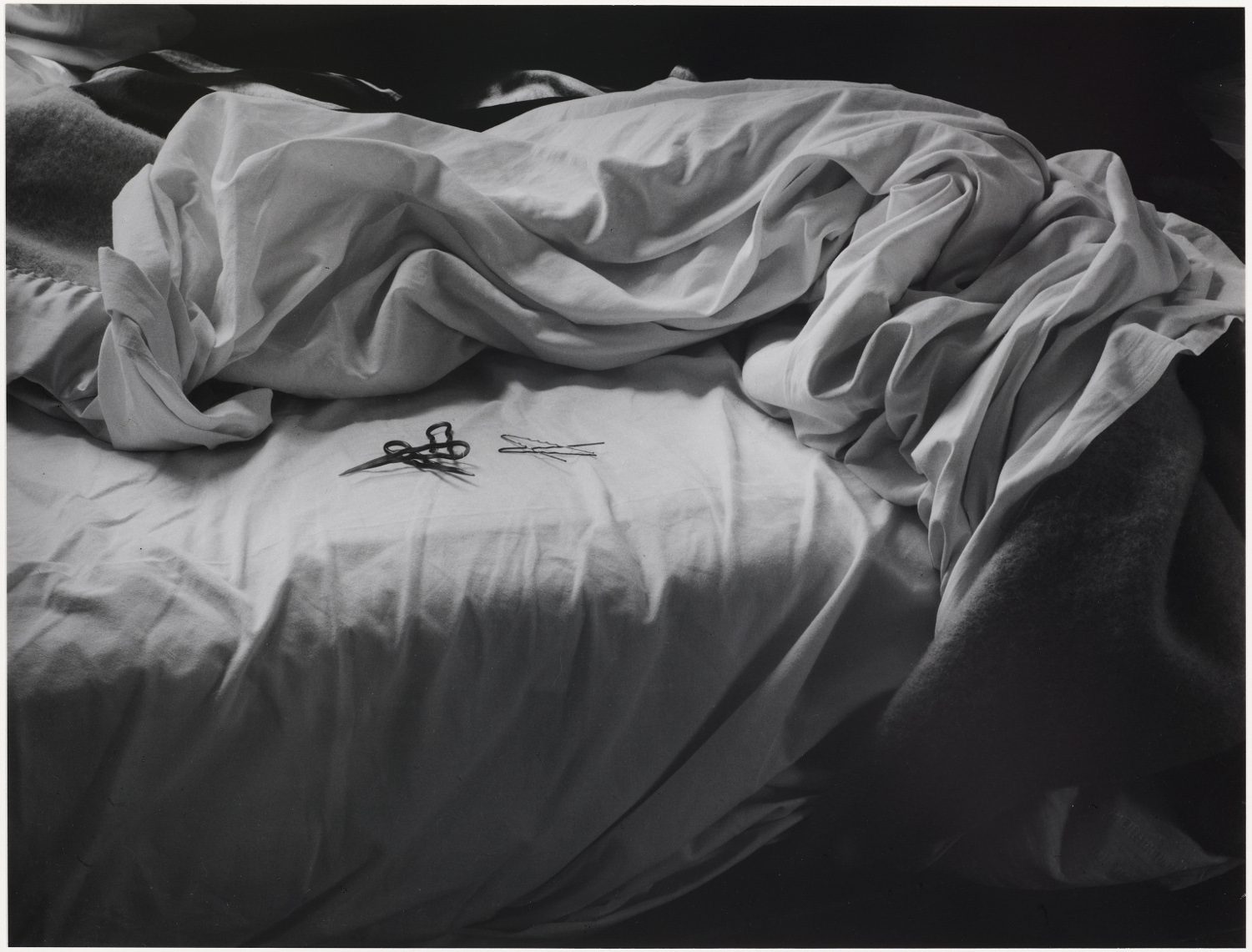

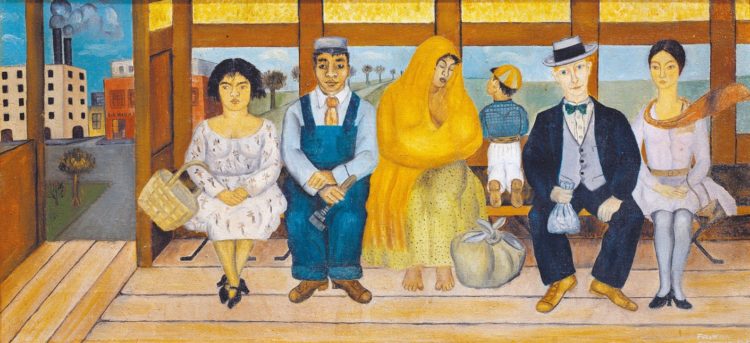

In 1905 or thereabouts, while she was studying chemistry in Seattle, Imogen Cunningham purchased her first camera and started by developing her photos in a homemade way. Before long she became the assistant of Edward S. Curtis, the famous photographer of American Indians, and discovered pictorialist photography in Camera Work, Alfred Stieglitz’s magazine. In the autumn of 1909, she went to Dresden to undertake research into the improvement of photosensitive paper. Back in Seattle in 1910, she opened a studio and specialized in portraits with blurred outlines, as were then being produced by Clarence H. White and Edward Steichen, as well as allegorical scenes (Eve Repentant, 1910). At that time she was fully involved in the pictorialist movement of the Photo-Secession Group, and handled negatives and printing paper. Under the influence of the photographers Gertrude Käsebier, and Anne Brigman, she became keenly involved in nude photography, which she helped to revolutionize. Bodies were shown in a naturalist way, for their formal beauty, and woman was not presented as an object of desire but as a matrix-like place (Two Sisters series, 1928). For her male nudes, also frozen in nature, the engraver Roi Partridge, whom she had married in 1915, acted as her model—those photographs still shocked her contemporaries. In 1917 she settled with her family in California where she rubbed shoulders with Dorothea Lange and Edward Weston, the leading figure of “live photography”. While receiving her first portrait commissions, she practiced experimental photography. In tandem with luminous abstractions, she worked on botanical motifs (Magnolia Blossom and Tower of Jewels, 1925). These images earned her comparison with the movement headed by Albert Renger-Patzsch, photographic leader of the German New Objectivity tendency, and its American equivalent, Precisionism. In this spirit, from 1928 on, she photographed America’s industrial landscapes.

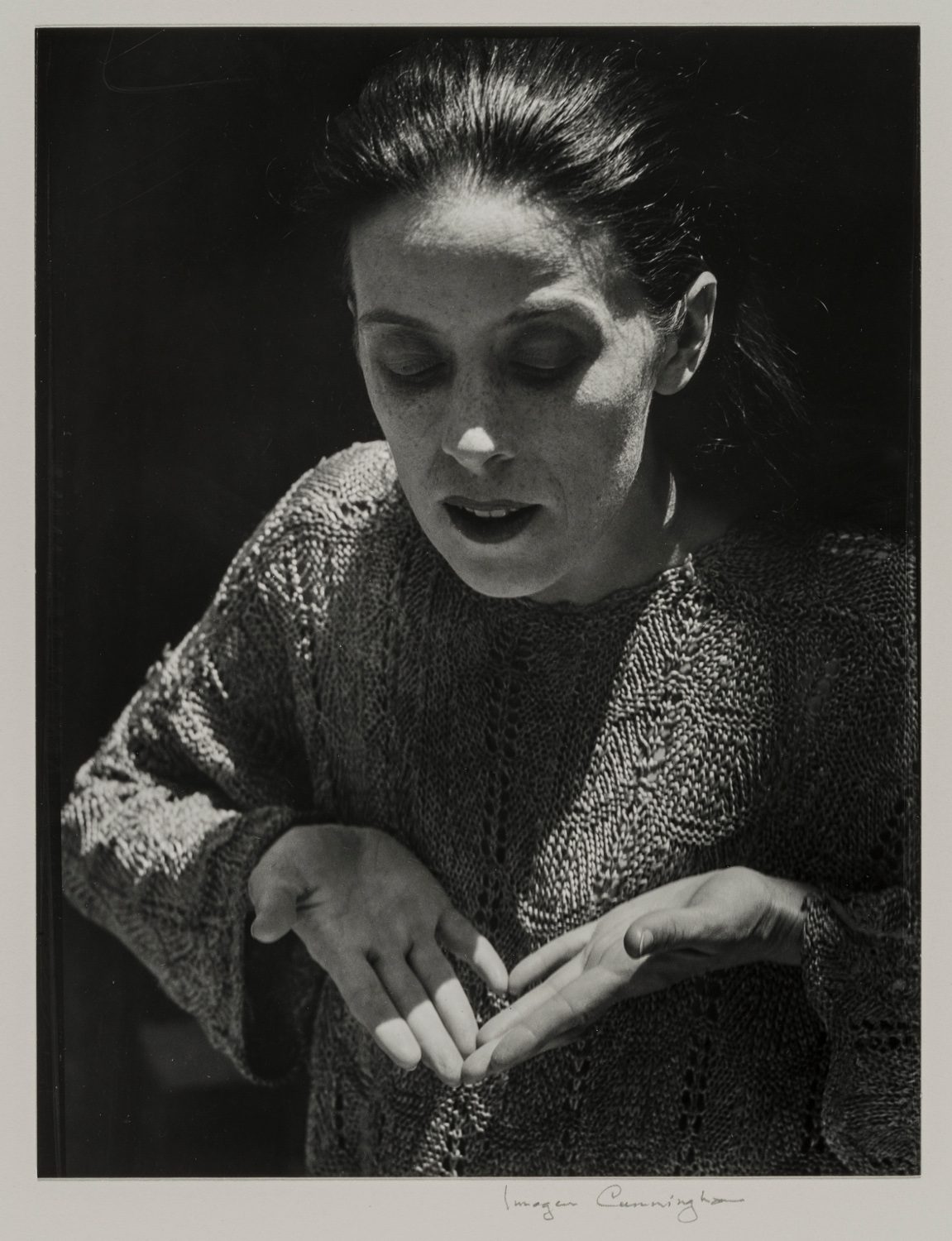

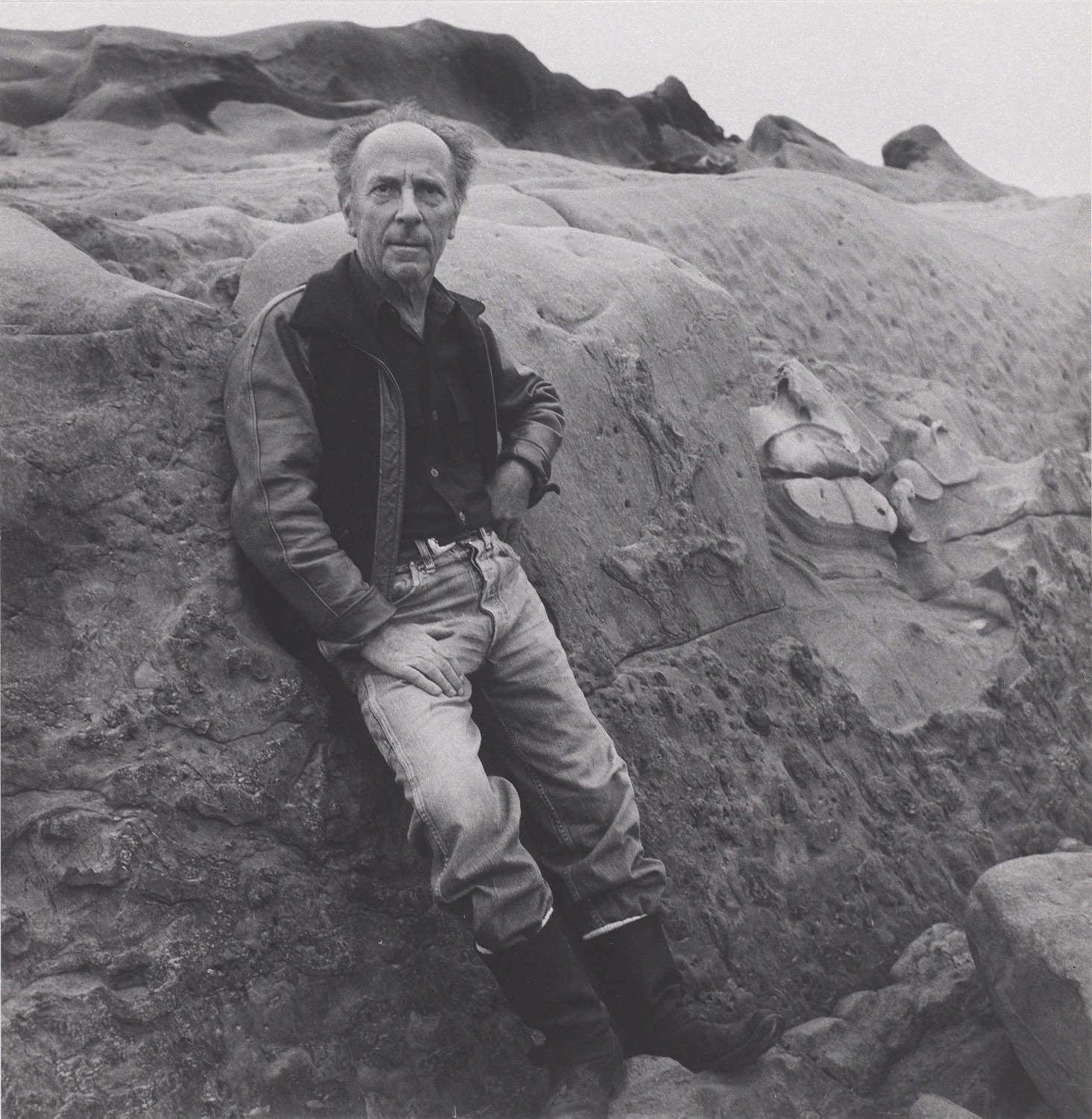

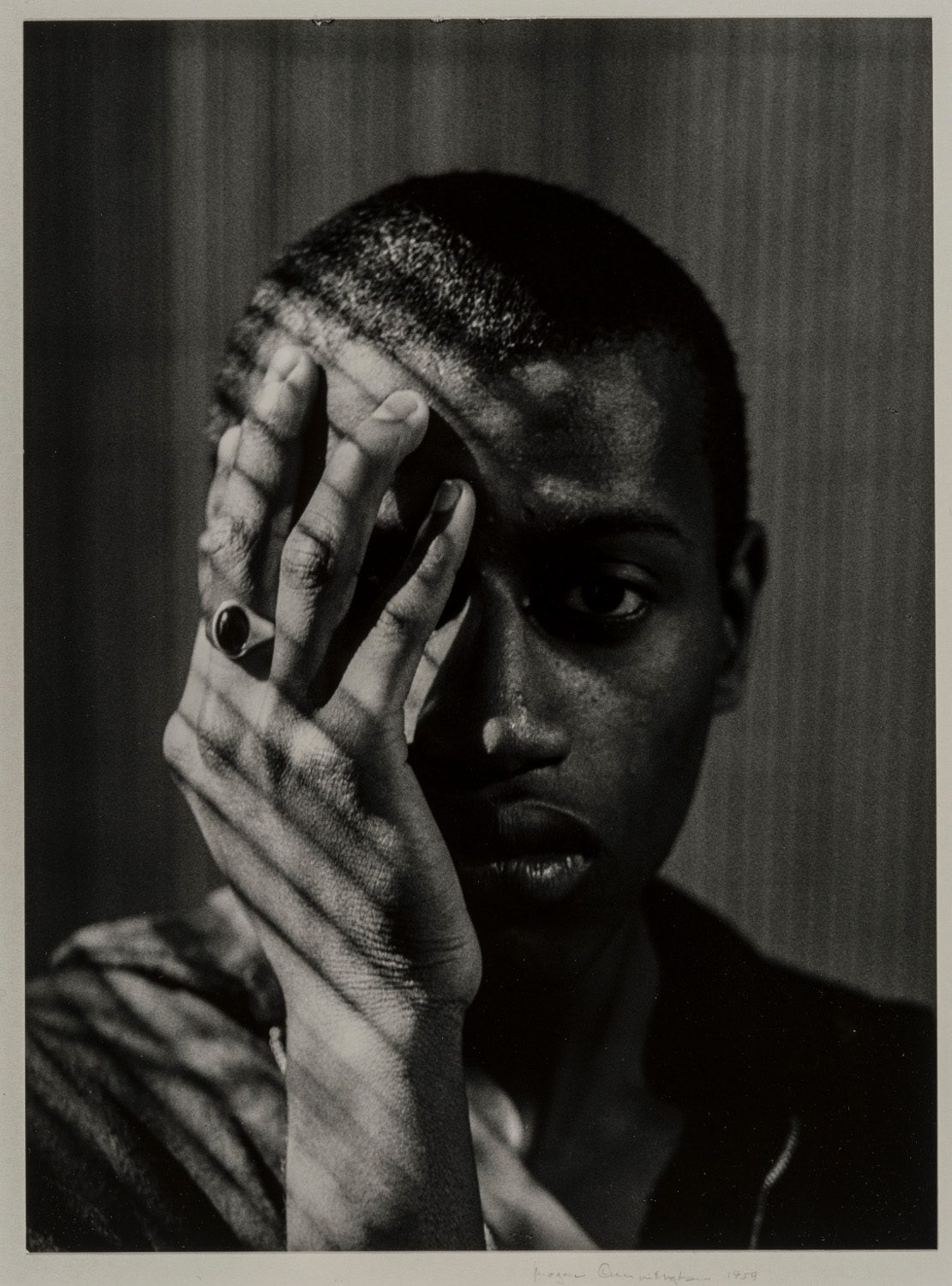

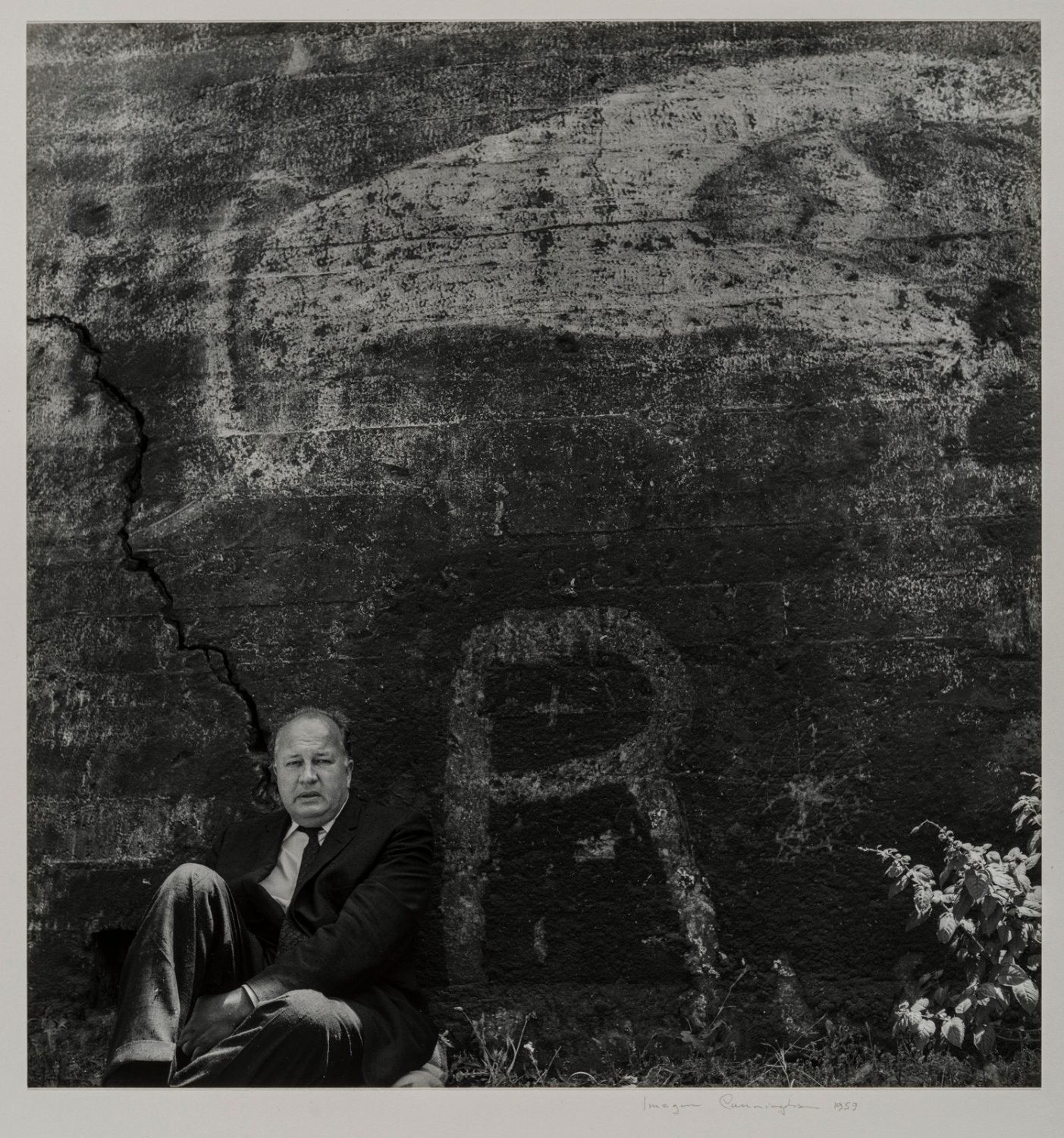

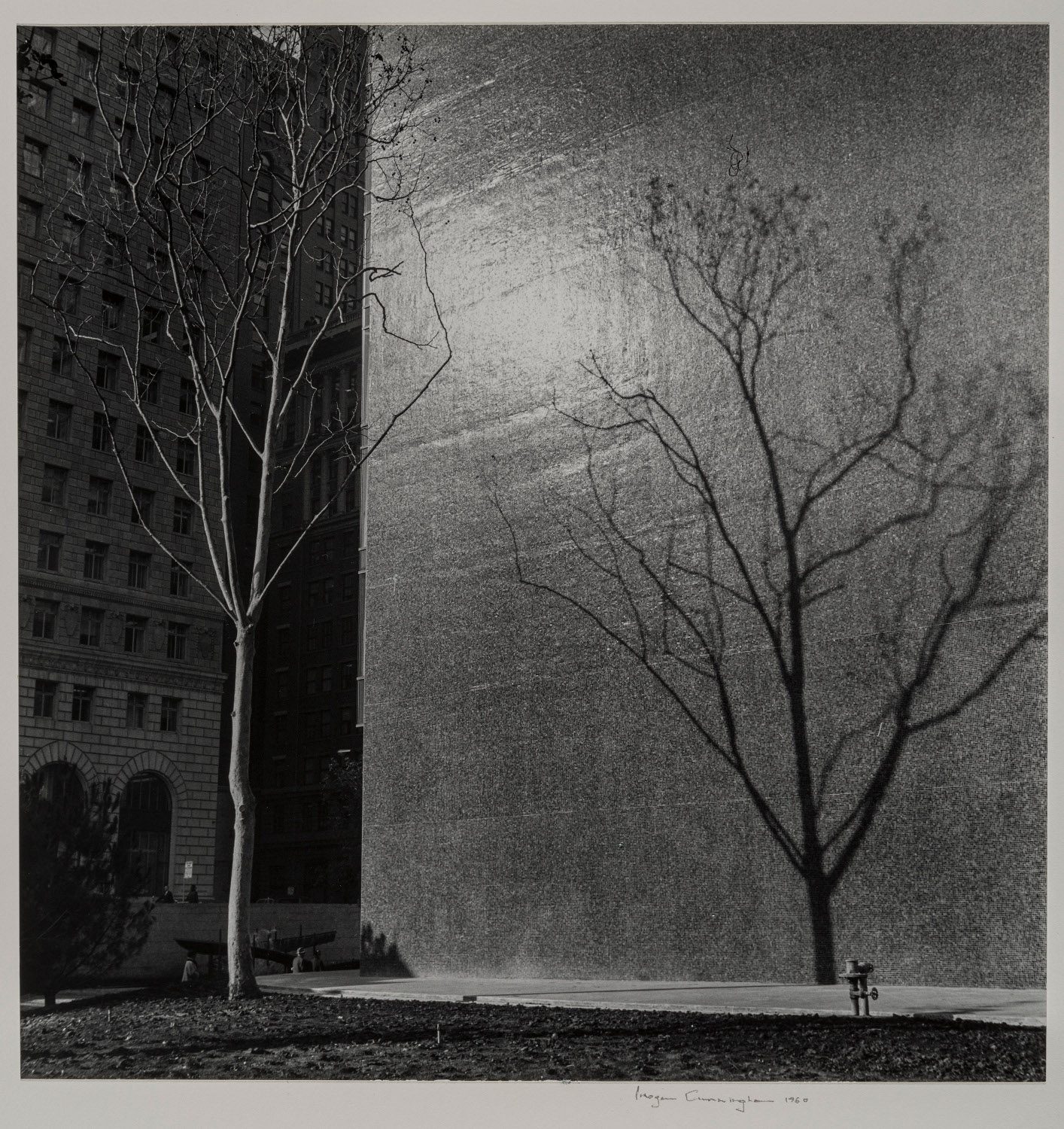

At the end of the 1920s, having become a leading photographer on the international scene, she was introduced to modernist circles, and in particular the exhibition Film und Foto (Stuttgart, 1929), by Weston, who was full of praise for her work. The year 1931 saw the start of her productive collaboration with the dancer Martha Graham, photos of whom were published in Vanity Fair, an experience which gave her a chance to further develop the techniques of photomontage and superimposition. In the 1930s, she photographed celebrities, without any retouching and in a more natural way than in a studio. Together with Ansel E. Adams and E. Weston, she thus found herself drawn into the f/64 group adventure which was advocating “live photography”. She tried her hand at urban documentary photography in New York, and then took part in the boom of photojournalism by traveling in the American west to photograph sawmills and oil refineries. After the war, she taught at the California School of Arts, where her colleague, Lisette Model, opened the doors to New York circles for her: the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) commissioned prints from her, and for her 73rd birthday, the Limelight Gallery offered her her first solo show, in 1956. In New York, she rediscovered the documentary vein with what she called “street documents” (Boy in New York, 1956), but in Europe, too, where she took a large number of pictures and encountered photographers like Man Ray, of whom she would produce several portraits in 1961. That visit revived her liking for experimental photography and, until the end of her life, she produced solarizations, inversions, double exposures, and superpositions of negatives. The 1960s were also years of protest and she photographed many pacifist marches and meetings. In 1970, she obtained a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation to print her old negatives. She enjoyed fame at the end of her life: in 1973 there were major exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Witkin Gallery in New York. She continued taking photographs until her death, all the while archiving her work. Her last series, After Ninety, a set of portraits of elderly people, was published posthumously in 1977. Her Photographs were exhibited in 1984 at the des femmes gallery in Paris. Cunningham was a feminist, without being militant. Her outstandingly rich career, a combination of technique and poetry, justified the short manifesto text which she wrote in 1913, Photography as a Profession for Women, by showing that a woman could become a very great photographer.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Portrait of Imogen Cunningham - I Believe in Learning (Ch 1)

Portrait of Imogen Cunningham - I Believe in Learning (Ch 1)  Portrait of Imogen Cunningham - The Iconic Magnolia (Ch 5)

Portrait of Imogen Cunningham - The Iconic Magnolia (Ch 5)  Portrait of Imogen Cunningham - Vanity Fair (Ch 8)

Portrait of Imogen Cunningham - Vanity Fair (Ch 8)