Marisol Escobar (dite Marisol)

Magical Mixtures: Marisol Portrait Sculpture, exh. cat., Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. (1991), Washington D.C., Smithsonian Inst. Press, 1991

→Pacini Marina (ed.), Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper, exh. cat., Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis (14 June 2014 – 7 September 2014), Memphis, Yale University Press, 2014

Marisol Retrospective Exhibition, Kagoshima City Museum of Art, Kagoshima, 1995; Iwai City Art Museum, Fukushima, 1995; The Museum of Modern Art, Shiga, 1995; The Hakone Open-Air Museum, Kanagawa, 1995

→Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art Memphis, June 14, 2014 – September 7, 2014 ; el museo, New York, 9 October 2014 – 10 January 2015

American-Venezuelan sculptor.

Born to an opulent Venezuelan family, Maria Sol Escobar spent her childhood following her parents on their journeys and attending their high society soirees. Her artistic training was irregular, eclectic and mostly self-taught: she studied at the Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1949 before moving to New York in 1950, where she briefly joined the Arts Student League, then the Hans Hofmann School for a longer period (1951-1954), located in the Greenwich Village of the Beat Generation. Her early years were marked by abstract expressionism – the dominant style in America after the war. However, the roots of her work are most visible in her teacher Hofmann and his “push and pull” colour theory (based on the attraction or repulsion between chromatic associations). But the young woman preferred sculpture to painting and, although she chose to colour her pieces, her way of working with materials, especially wood, and later plaster, objects, and electricity, remained at a distance from any formal legacy. By the late 1960s, her style and reputation were established.

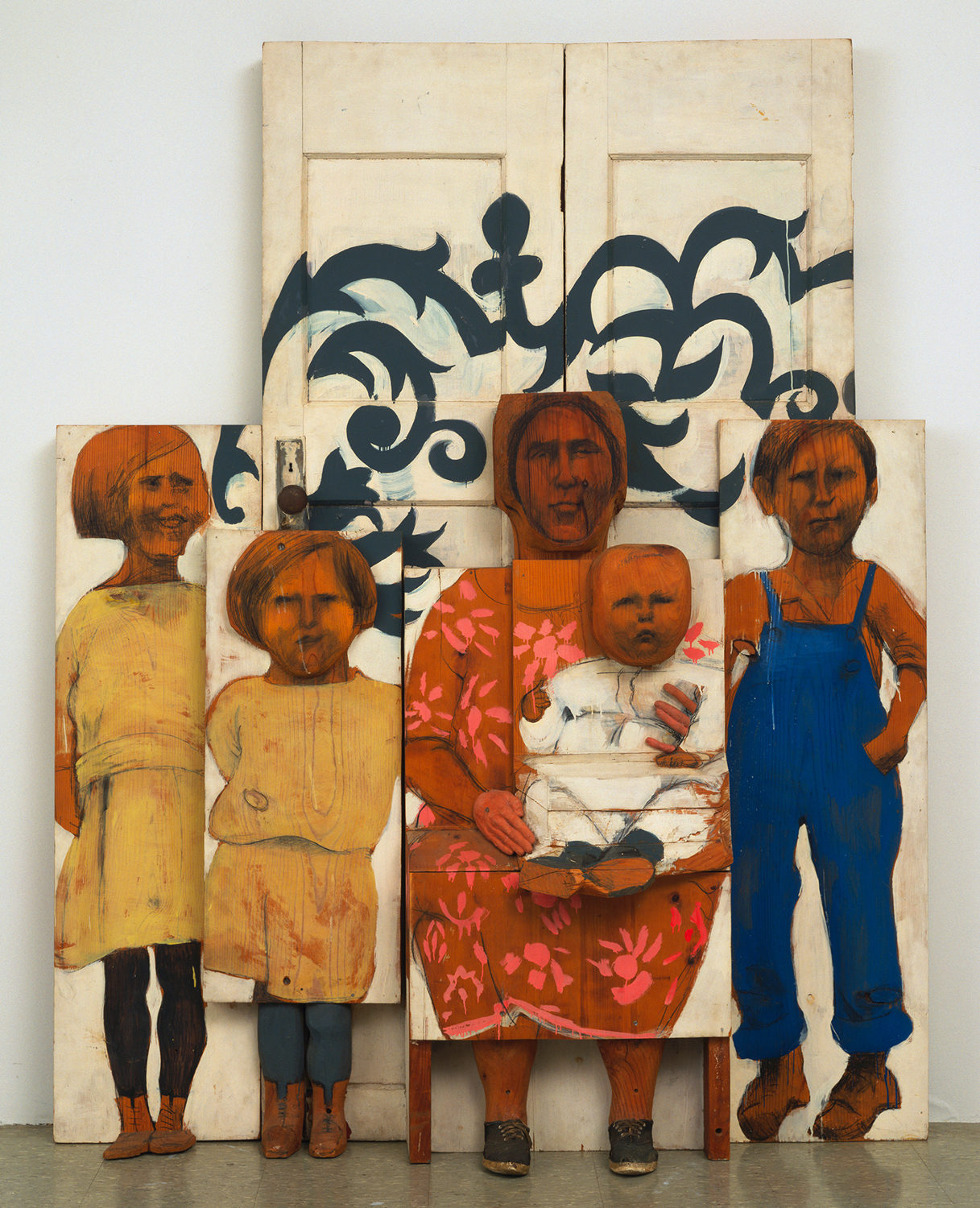

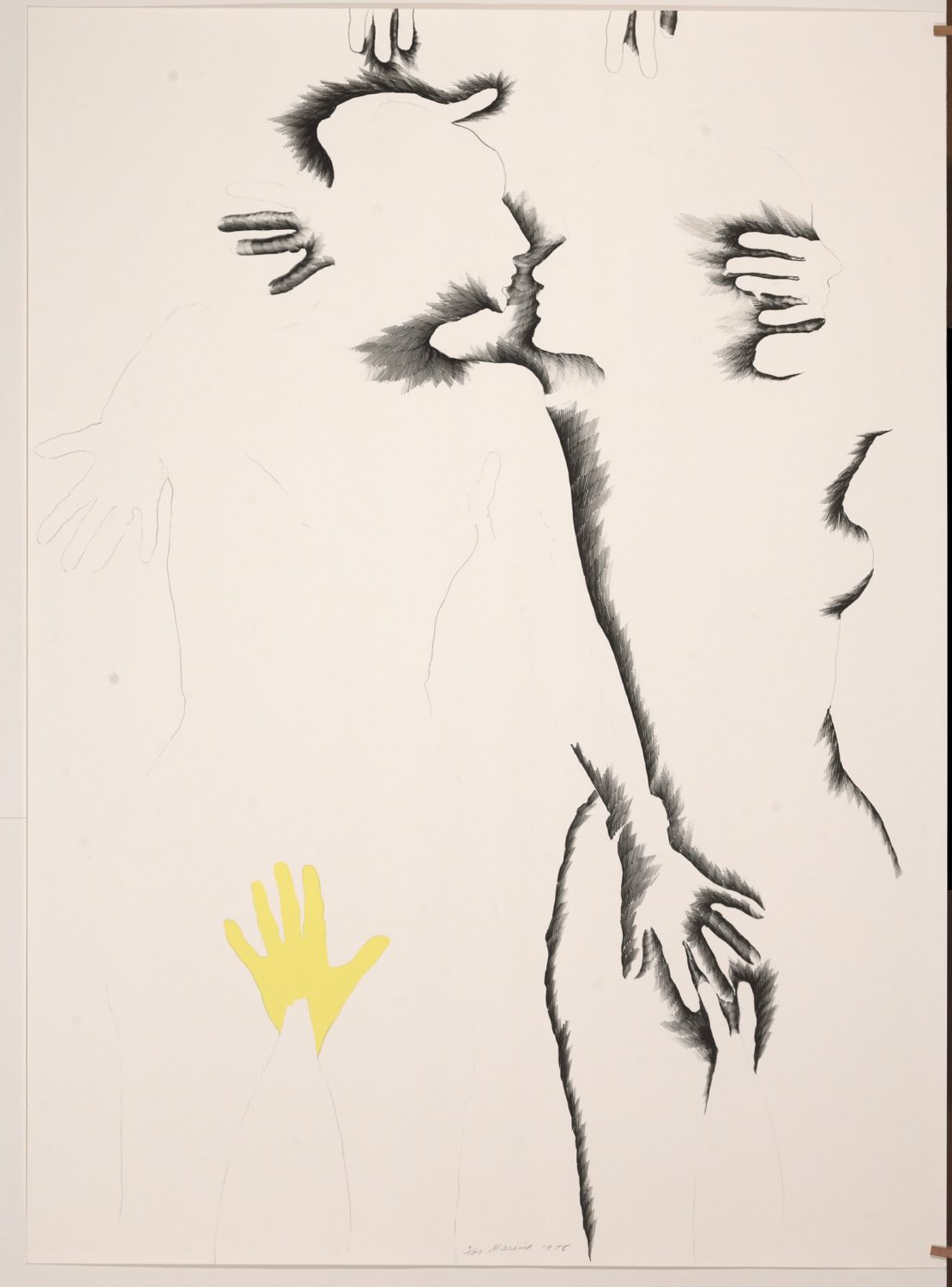

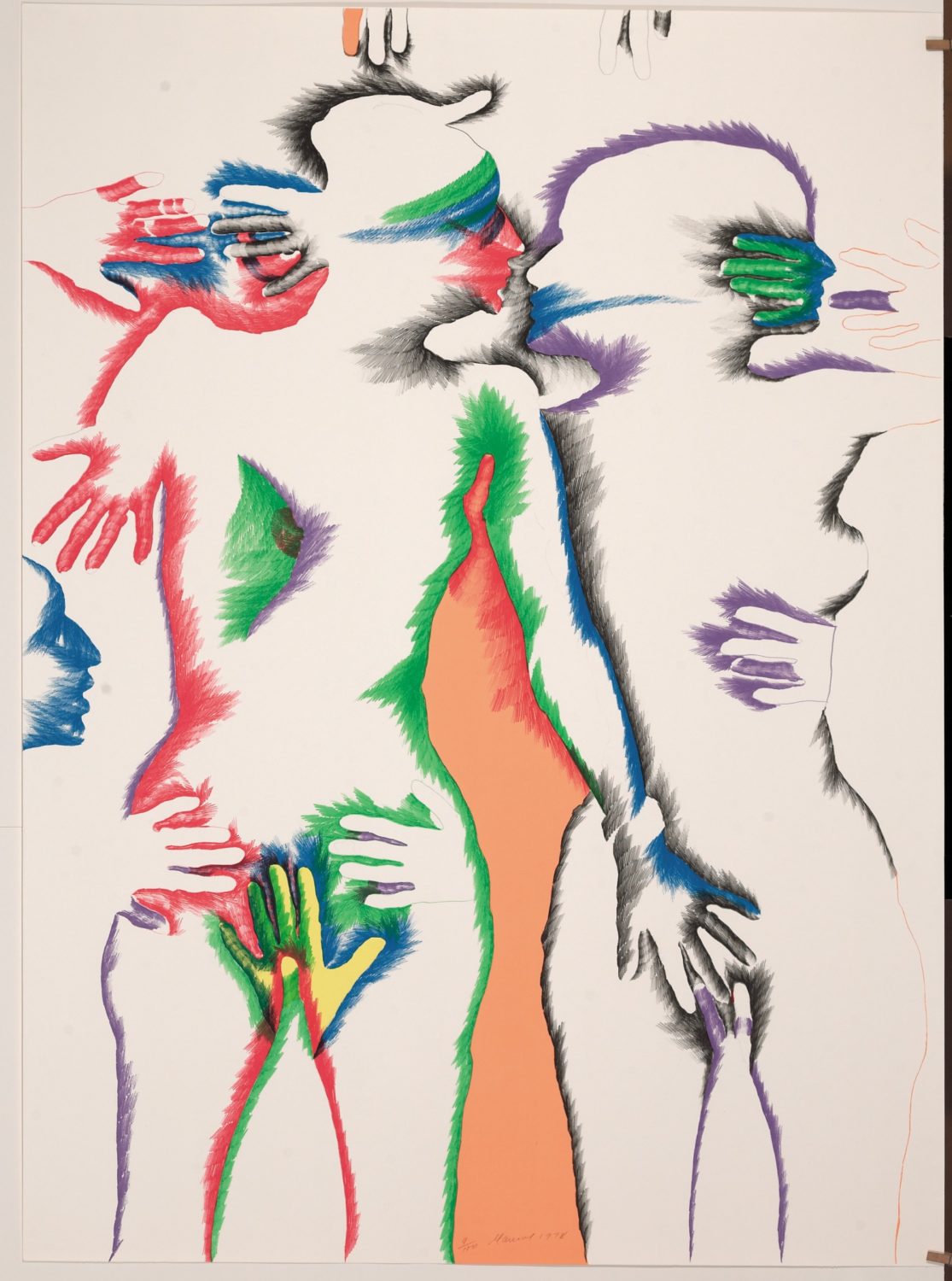

Her part in Andy Warhol’s 1963 experimental film Kiss immortalised her affiliation to Pop Art. Her reputation as a “party girl” in the magazines and the very nature of her name (Marisol, “sea and sun”) were instrumental in making her an icon. And yet, although her wide-ranging subjects were often inspired by the “trivial” aspects of life which brought fortune to Pop Art, the works she exhibited as from 1958 at the Castelli Gallery in New York, then at the famous Stable Gallery – a supreme recognition and the start of her celebrity – in 1962, and later still at the Venice Biennale, stand out from the movement even more in that they contain a strong element of social satire. Her large groups of simple, rigidly shaped figures associate two and three-dimensional elements in novel ways. Working on mostly rectangular wood blocks, she carved out only a few body parts, such as the legs and heads with many faces (Women and Dog, 1964) and painted the figures’ different profiles (face, side view, back). Only a few parts manage to pull through this flat frontality, at once reminiscent of medieval column statues, Native American totems, and Hofmann’s theories – the heads, glued, painted on or sculpted; and sometimes the hands, the sole signs of expression of these lifeless masks lined up next to each other in voluntary solitude. Thus extracted from the block, as if dissected, these elements (hands, breasts, heads) emphasise other objects, like ready-mades, found or made by the artist, such as a lead, a bag, photographs, and the stuffed head of a dog in Women and Dog.

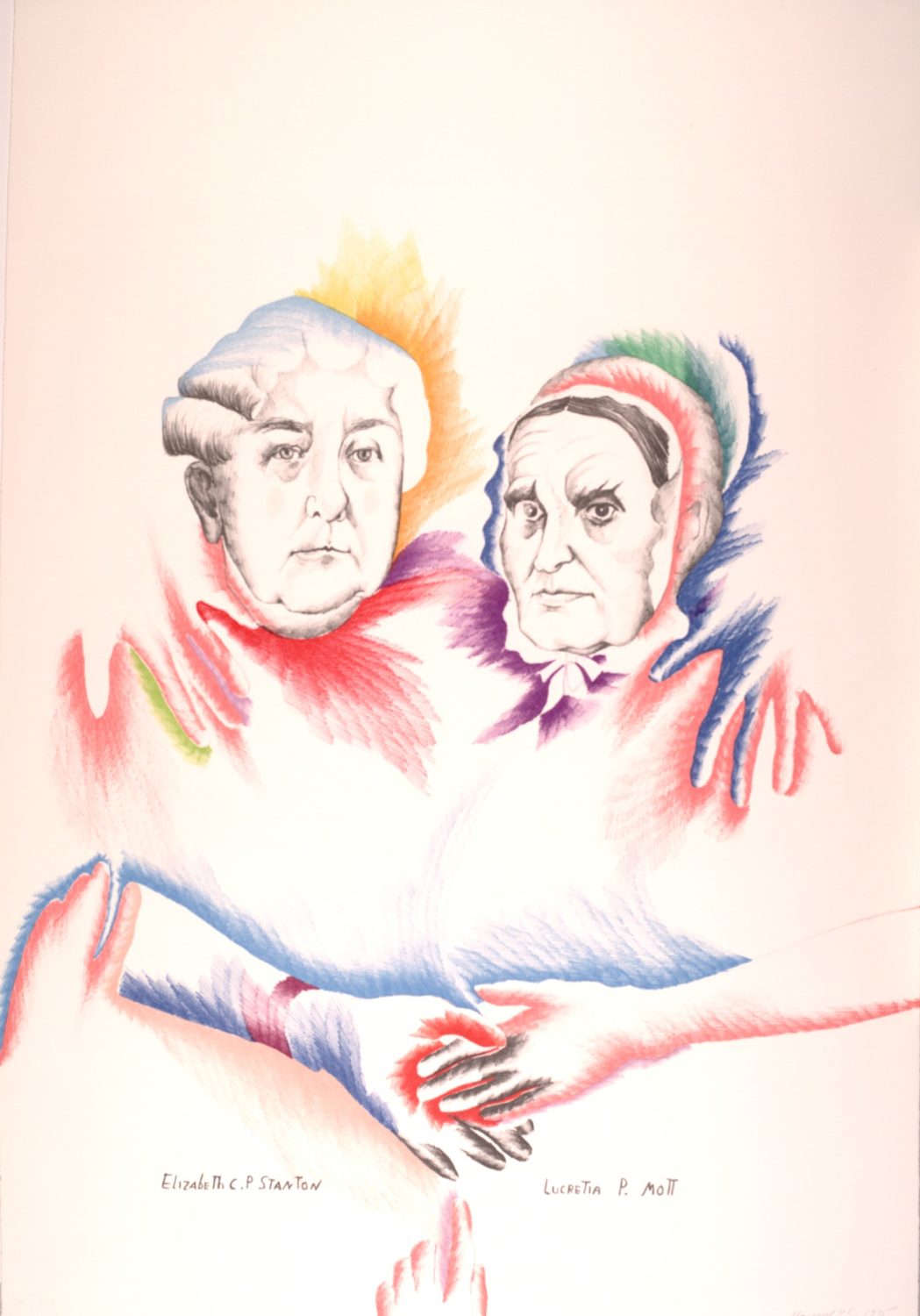

The sculptor is also known to use plaster prostheses to depict breasts, which are a recurring feature in a work that acerbically criticises American society in the 1960s: the condition of women and of the traditional family (The Family, 1962), consumer society, and also world leaders and celebrities, as did Andy Warhol, of whom she made portraits (1962-1963). The 1970s saw Marisol reverting to sculpture in its ancient celebratory function and paying tribute to her artistic masters and to major figures of American history in the 1980s. In addition to her depictions of specific personalities – President Charles de Gaulle (1967), Louise Nevelson, John Wayne, Mark Twain, or Queen Elizabeth – the artist sculpted multiple and singular portraits of herself: theatrically having dinner with herself (Dinner Date, 1963), marrying herself (The Wedding, 1962-1963), and spending evenings with 14 of her doubles (The Party, 1965-1966). Her face can also be found painted onto the bodies of sinuous fish (Fish series, 1970s). In 1982, her spectacular Last Supper shows the seated artist gazing at a stone Christ and his wooden apostles. Her sculptures can be said to constitute a complete and unusual reconstitution of a now dated society.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Ver Más: Los mercaderes, obra de Marisol Escobar

Ver Más: Los mercaderes, obra de Marisol Escobar