Focus

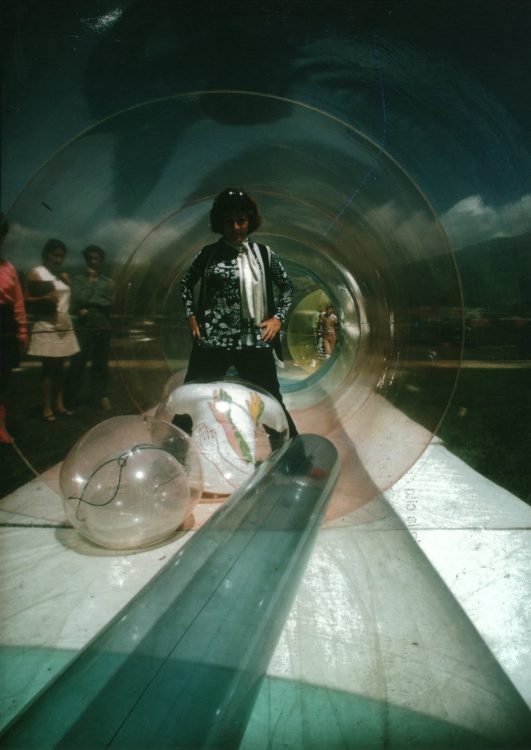

Women started to get involved in pop art as of the 1960s. Long considered as an Anglo-American movement, focussed around a limited group of male artists, it’s now a core element of a number of exhibitions (for instance The Ey exhibition, The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, 2015-2016; Power Up, Female Pop Art, Kunsthalle de Vienne, 2011) bringing to light a parallel effervescence of female artistic initiatives around the world. By taking possession of pop aesthetics, they have pushed back the boundaries of art, particularly through the use of new materials, such as vinyl, for example, in the works of Nicola L (Woman Sofa, 1968), and Kiki Kogelnik (Hangings, 1970) or the plastic objects used by Martine Canneel (Good Luck, 1979) and Niki de Saint Phalle (Lucrezia, 1964). It’s a heterogeneous movement that’s taking shape, driven by common underlying concerns. From Renate Bertlmann (Exhibitionism, 1973) to Évelyne Axell (Ice cream, 1964), Eulàlia Grau (Panic (Ethnography), 1973) and Martha Rosler (Cleaning the Drapes, 1967-72), many have demonstrated their political or feminist commitments through their works. Women artists have thus enriched the Pop art movement with a subjective and subversive language.

1935 — 1972 | Belgium

Evelyne Axell

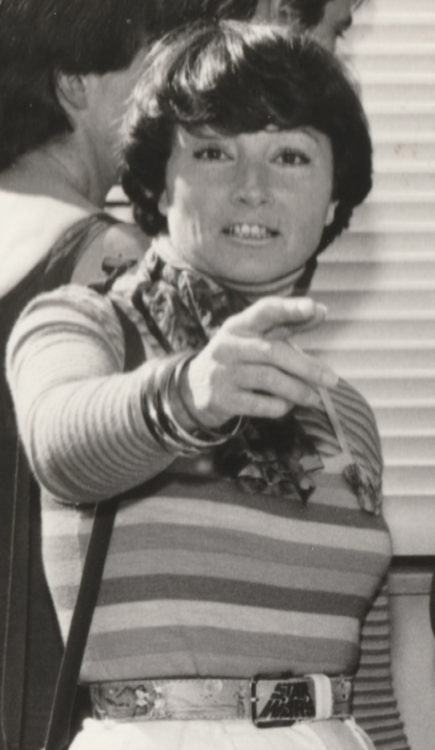

1943 | United States

Martha Rosler

1930 — France | 2002 — United States

Niki de Saint Phalle

1918 — 1986 | United States

Corita Kent

1935 — 1997 | Austria

Kiki Kogelnik

1942 | United States

Jann Haworth

1930 — France | 2016 — United States

Marisol Escobar (dite Marisol)

1932 — Morocco | 2018 — United States

Nicola L.

1947 — 2013 | Estonia

Anu Põder

1935 — 2021 | Peru

Teresa Burga

1938 | Colombia

Beatriz González

1943 | Argentina

Marta Minujín

1931 — 1999 | Poland

Maria Pinińska-Bereś

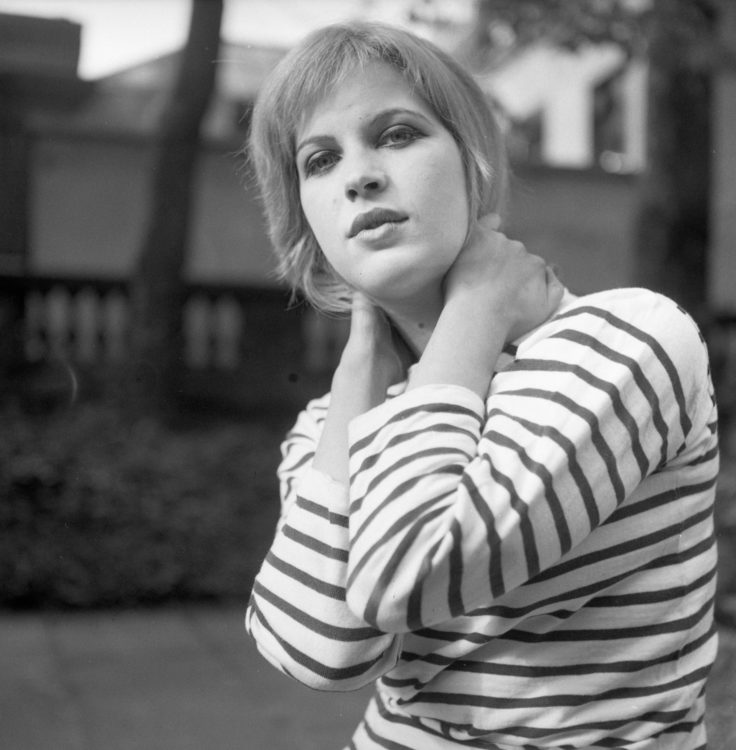

1938 — 1966 | United Kingdom

Pauline Boty

1944 | Spain

Ángela García Codoñer

1940 — 2018 | Germany

Christa Dichgans

1936 | Belgium

Martine Canneel

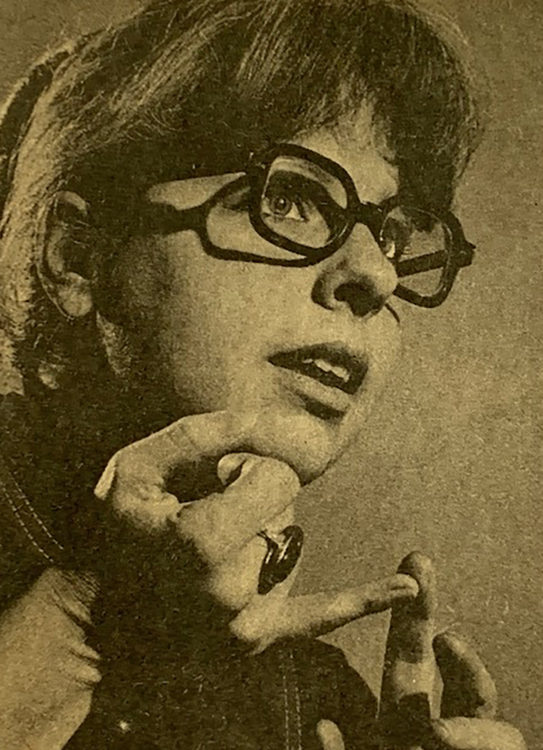

1926 | United States

Rosalyn Drexler

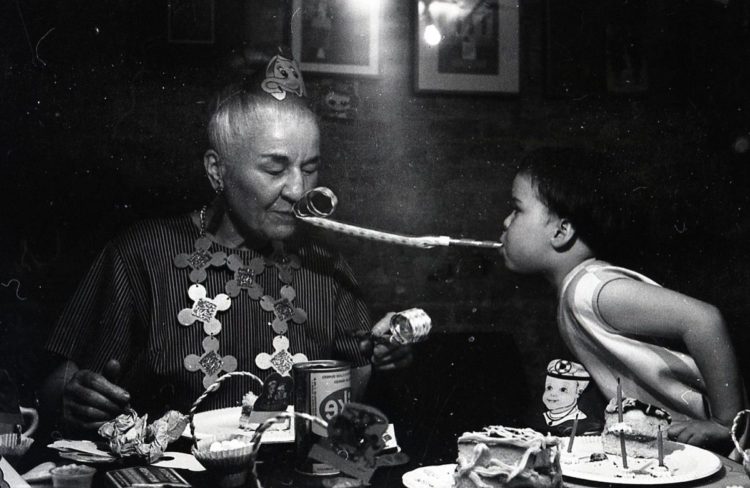

1905 — 1986 | United States

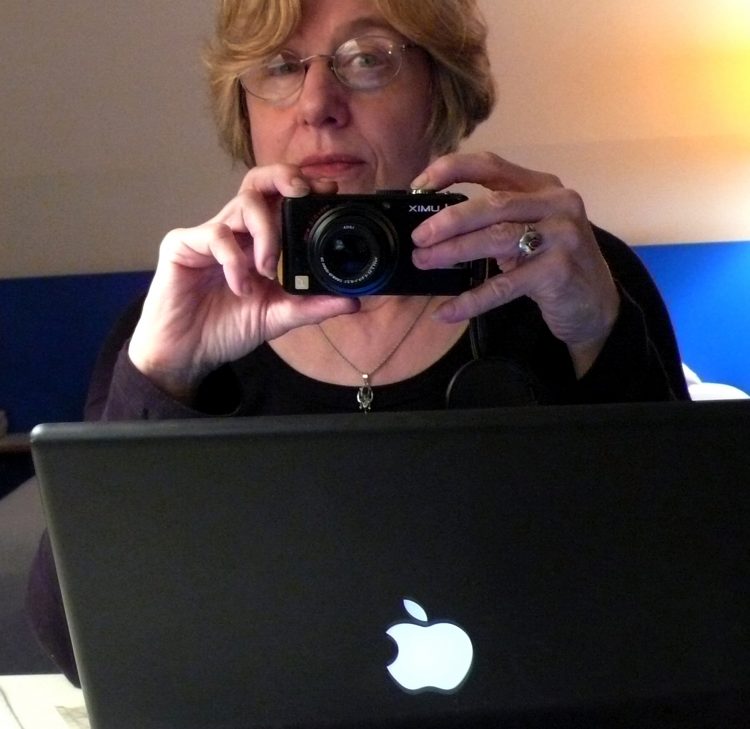

May Wilson

1944 | United States

Kay Kurt

1932 | Italy

Giosetta Fioroni

1946 | Spain

Isabel Oliver Cuevas

1933 — United States | 2022 — Germany

Dorothy Iannone

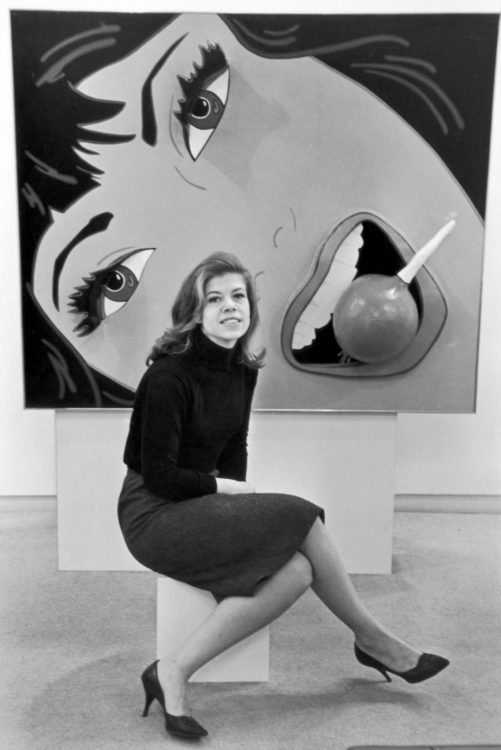

1931 — 2014 | United States

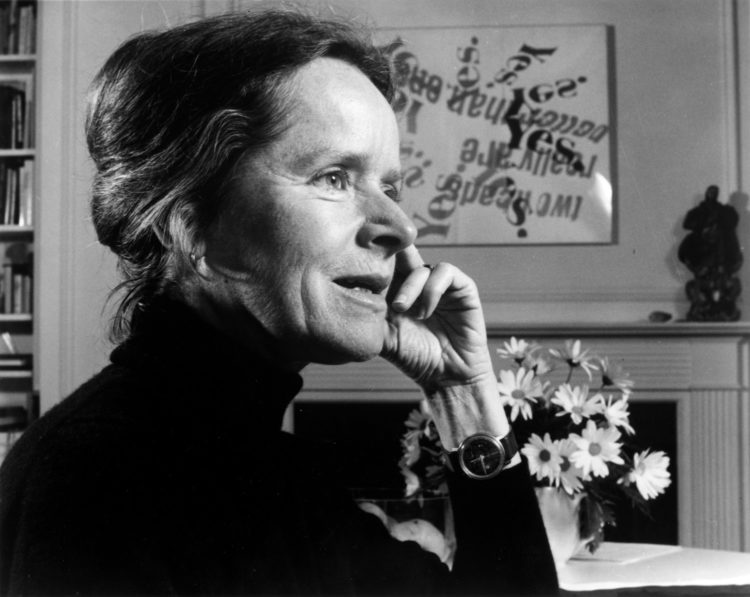

Marjorie Strider

1942 | Germany

Ulrike Ottinger

1936 — France | 2017 — United States

France Cristini

1939 — 2024 | Netherlands

Jacqueline de Jong

1929 — 2018 | United States

Marcia Hafif

1959 | Australia

Linda Marrinon

1945 | United States

Barbara Kruger

1925 — 2019 | Japan

Tsuruko Yamazaki

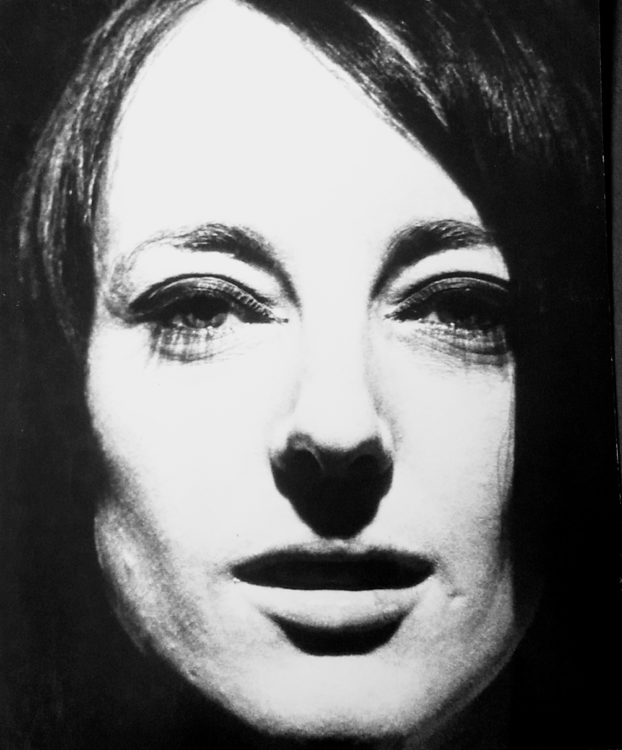

1929 — Poland | 1999 — France

Lea Lublin

1933 | Italy

Lucia Marcucci

1947 — 2013 | United States

Sarah Charlesworth

1940 — 2007 | United States

Elizabeth Murray

1956 | United States

Nomi Tannhauser

1967 | Uzbekistan

Dilyara Kaipova

1945 | Norway

Elisabeth Astrup Haarr

1942 | Spain

Mari Chordà

1960 — 2006 | Spain

Patricia Gadea

1970 | Israel

Khen Shish

1965 | Spain