Feltens, Frank (dir.), Japan in the Age of Modernization: The Arts of Ōtagaki Rengetsu and Tomioka Tessai, Washington, Smithsonian Scholarly Press, 2023

→Fister, Patricia, Japanese Women Artists 1600–1900, Lawrence, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1988

→Tokuda, Kōen, Ōtagaki Rengetsu, Tokyo, Kodansha, 1982

Meeting Tessai: Modern Japanese Art from the Cowles Collection. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 13 août 2022-18 février 2024

→Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection, musée d’Art de Denver, Denver, États-Unis, 13 novembre 2022-16 juillet 2023

→Ōtagaki Rengetsu-ni ten: Yūkyo no waka to sakuhin [Ōtagaki Rengetsu: Poésie et art d’une cabane rustique], musée d’Art de Nomura, Kyoto, 8 mars-20 avril 2014

Japanese poet, calligrapher, ceramist and painter.

Purportedly born the illegitimate daughter of a domanial lord and a courtesan, and experiencing profound familial loss before her early forties, the life of the Japanese Buddhist nun Ōtagaki Rengetsu (1791–1875) was defined by creativity in the face of difficulty. Originally named Nobu, she was adopted soon after her birth into the Ōtagaki family at Chion’in, a Pure Land Buddhist temple in Kyoto, likely at the request of her biological father, allegedly a member of the aristocratic Tōdō family.

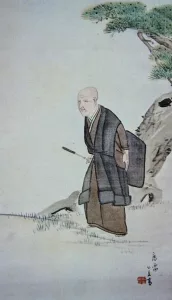

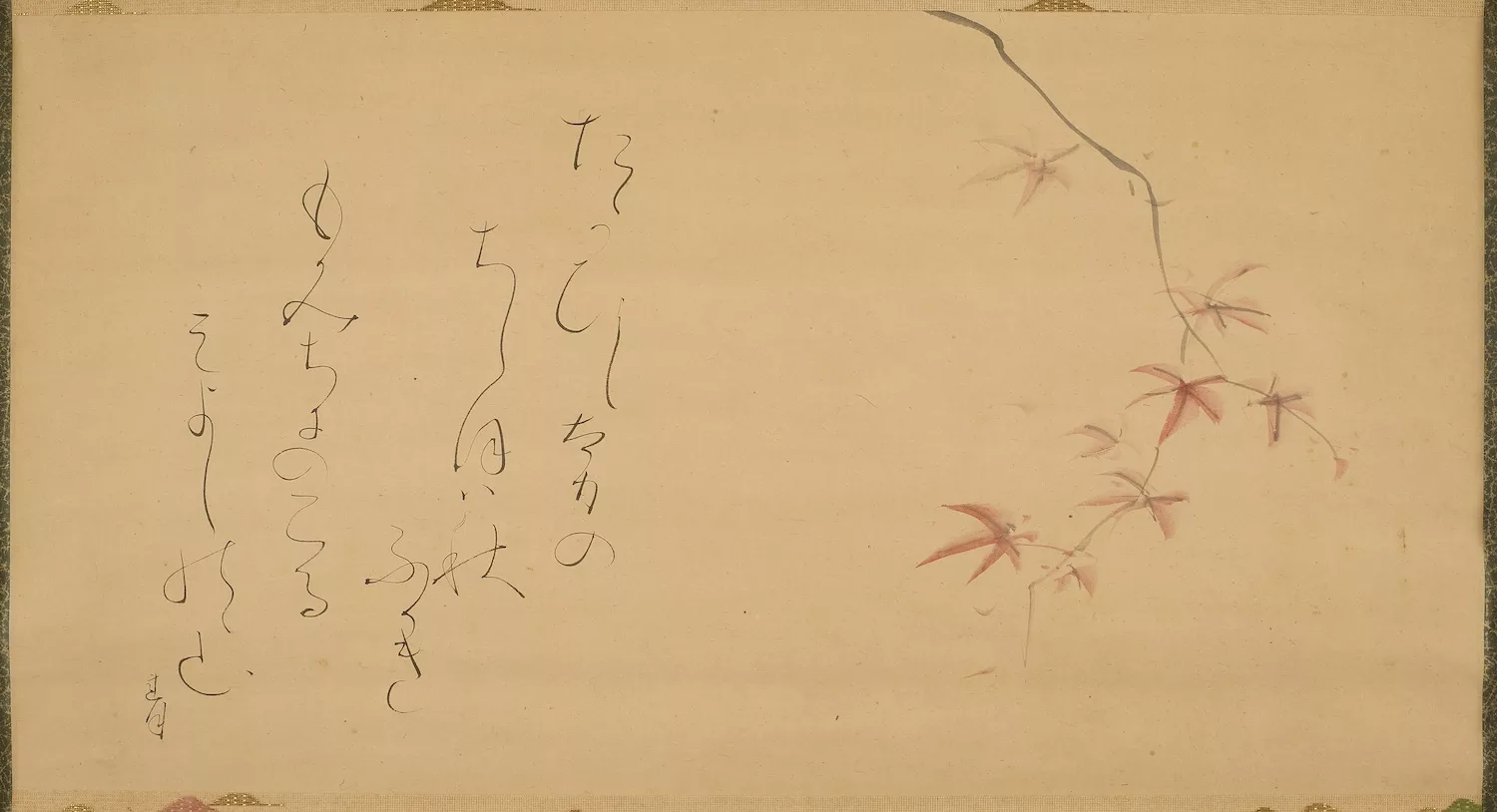

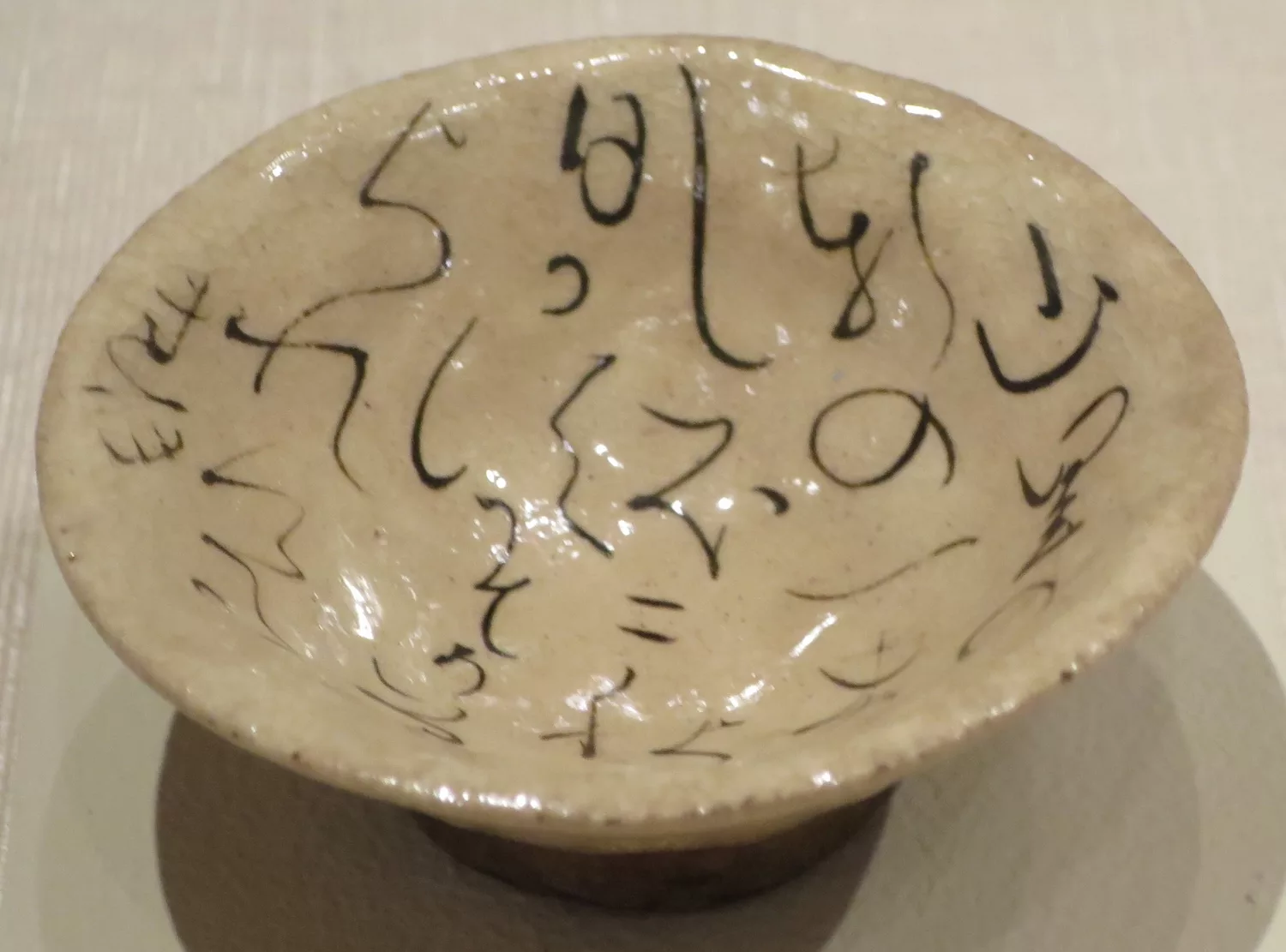

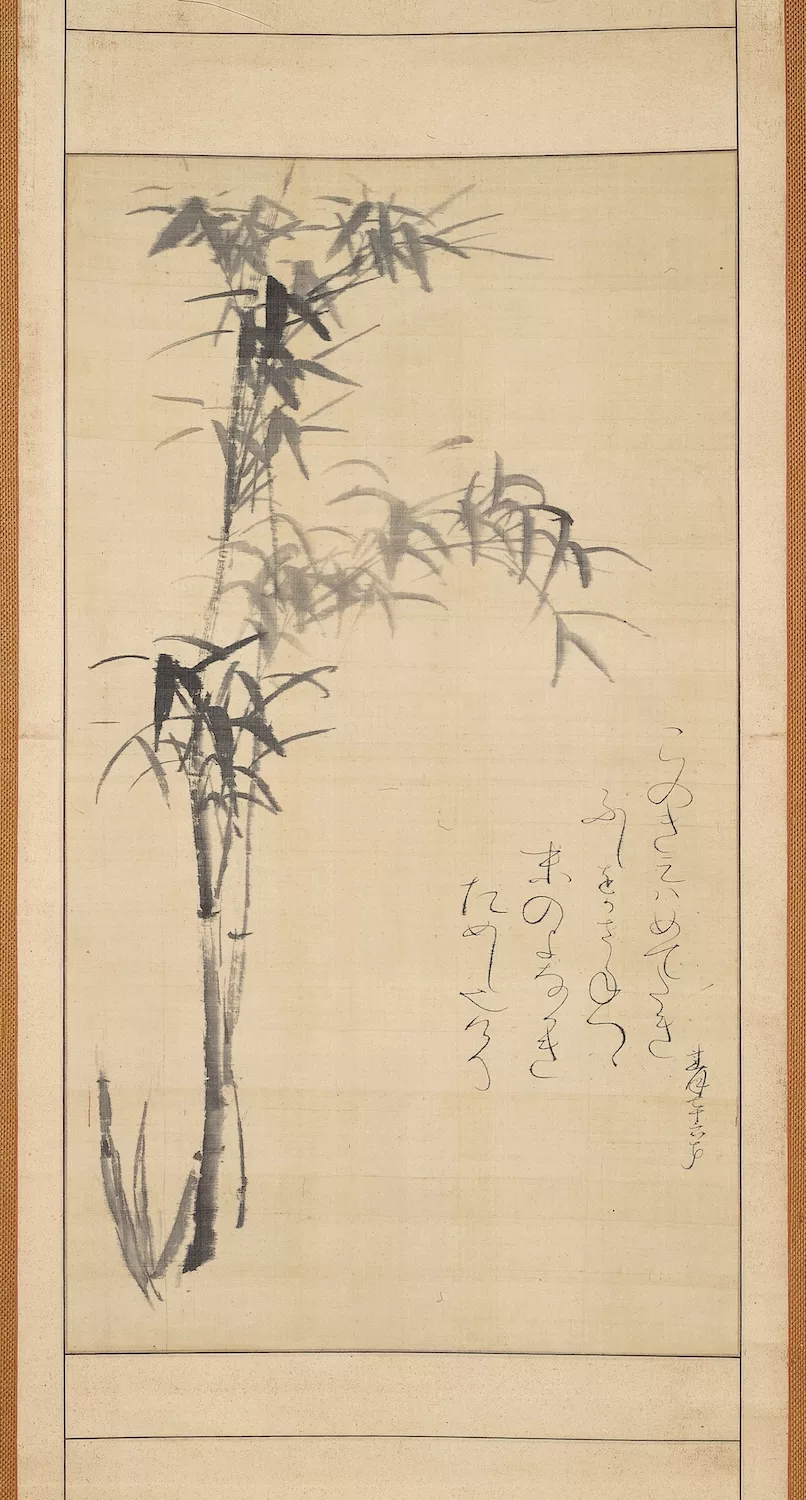

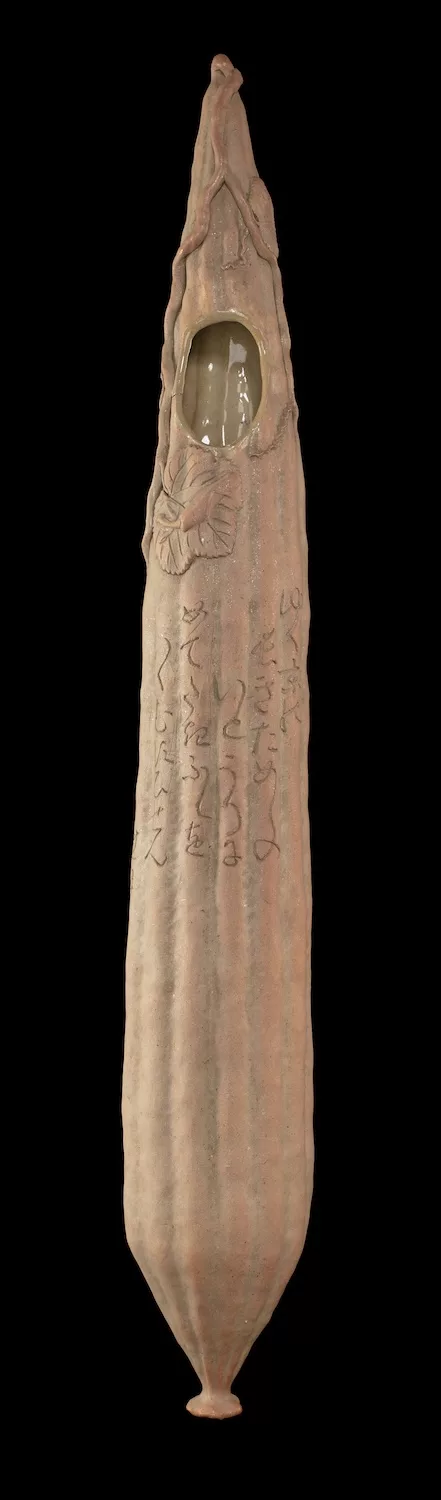

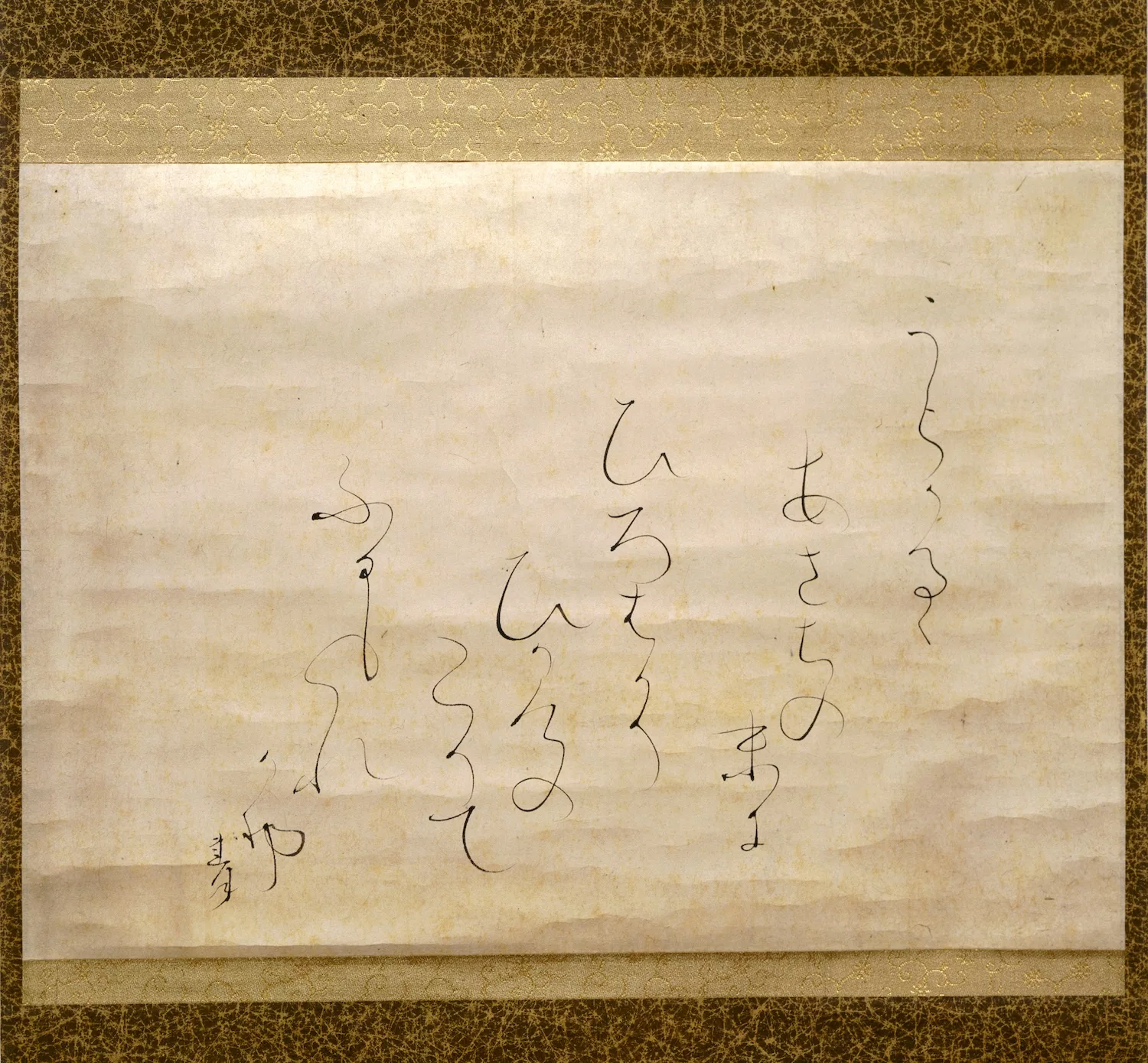

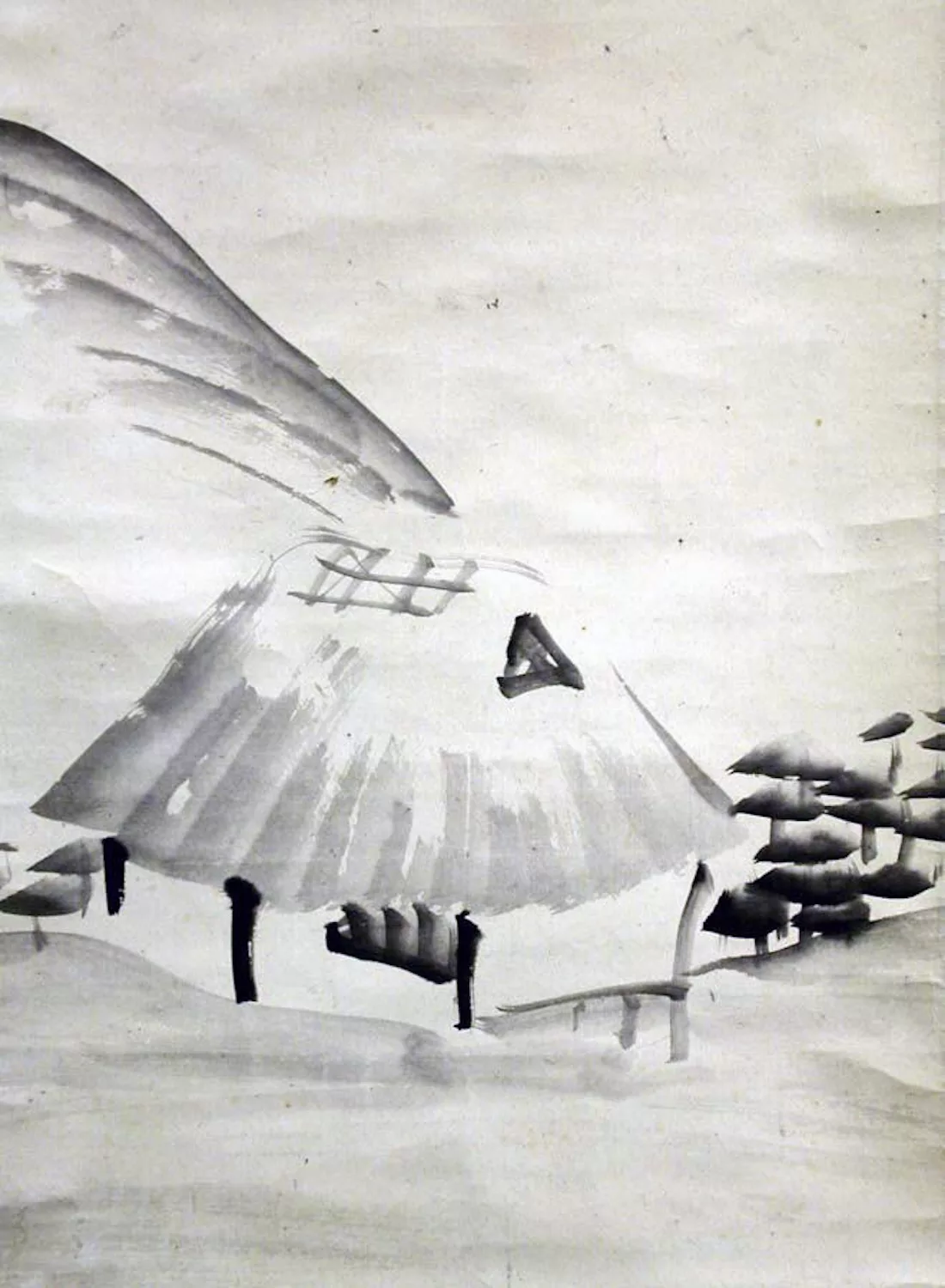

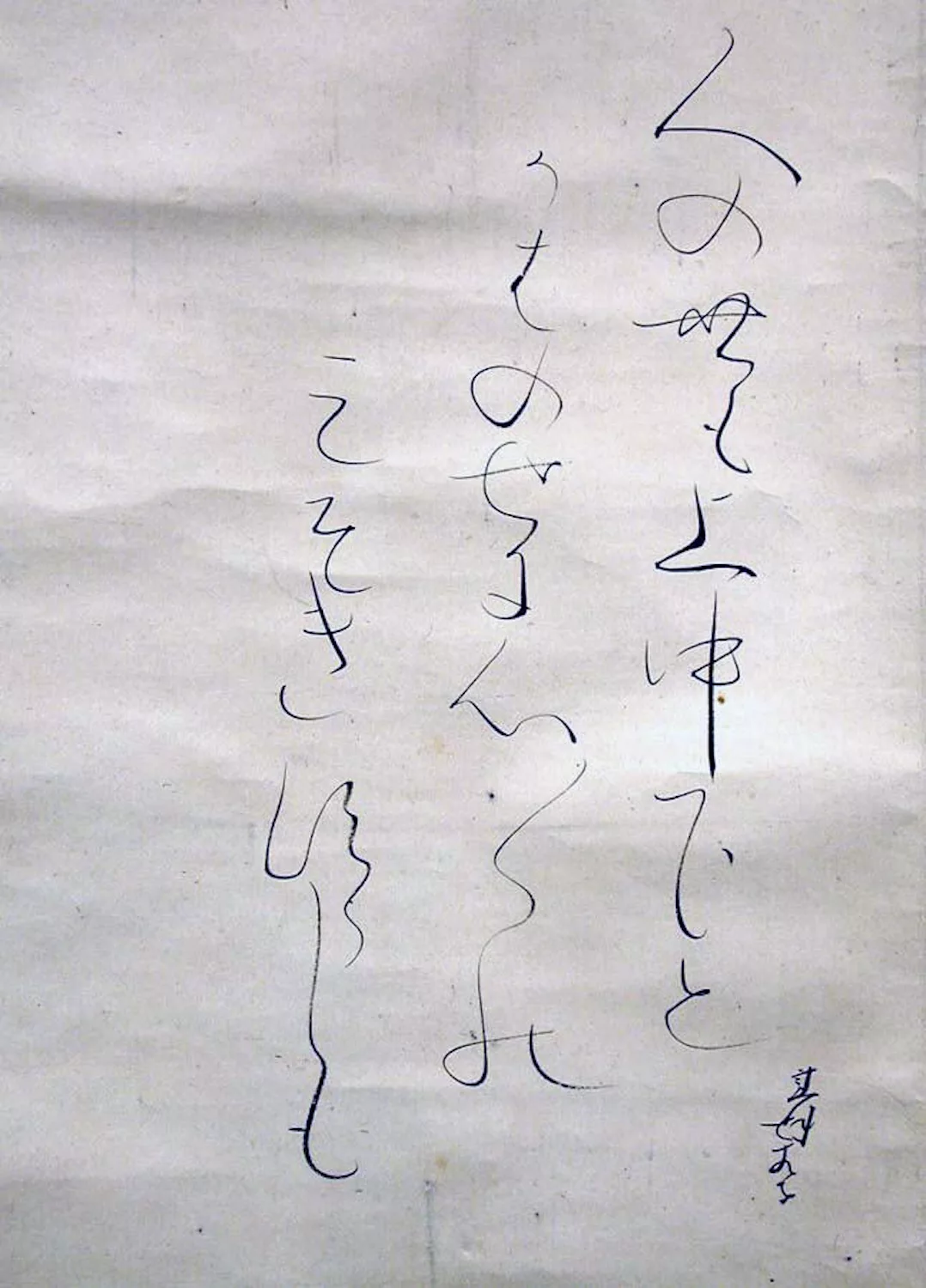

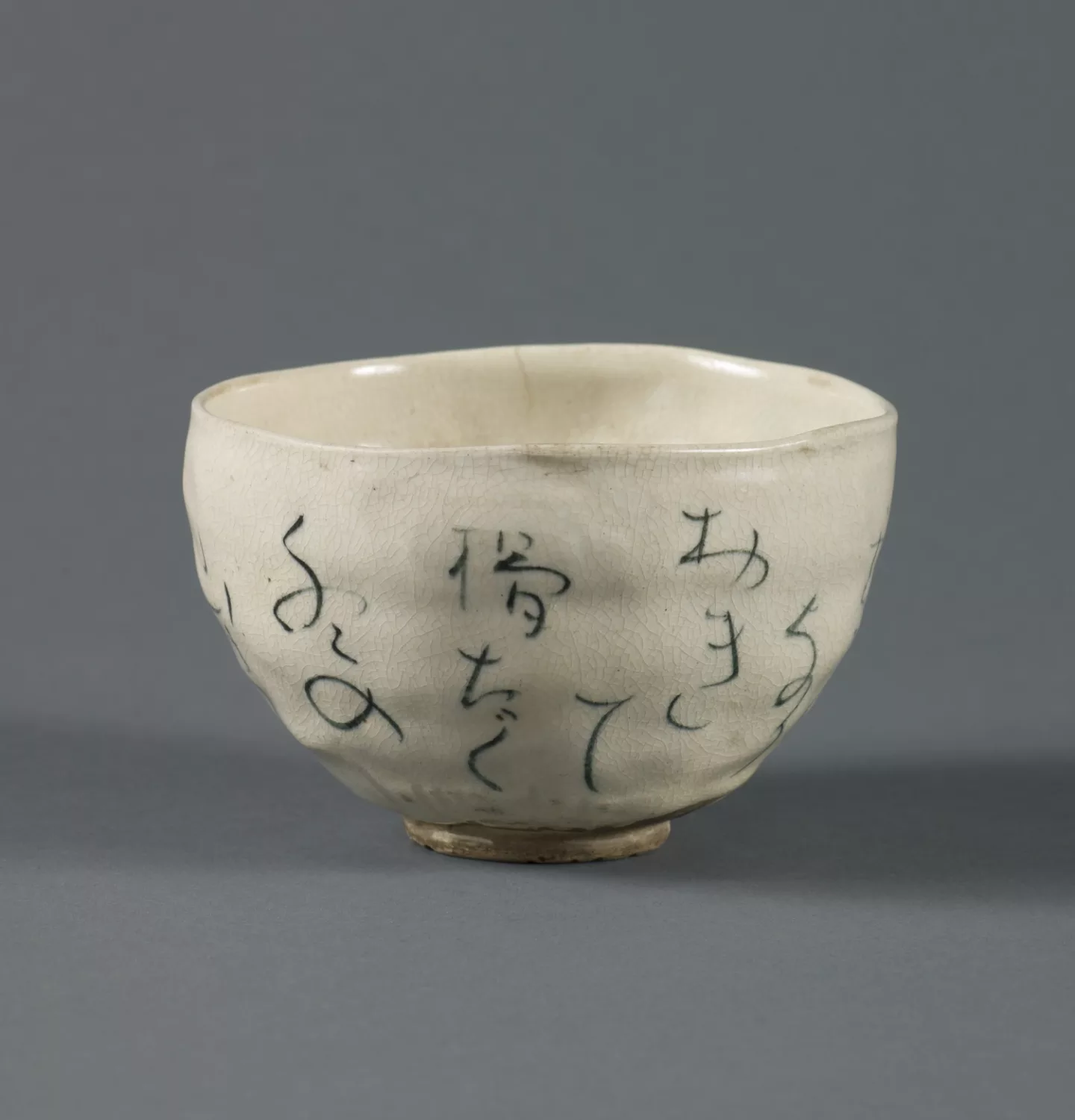

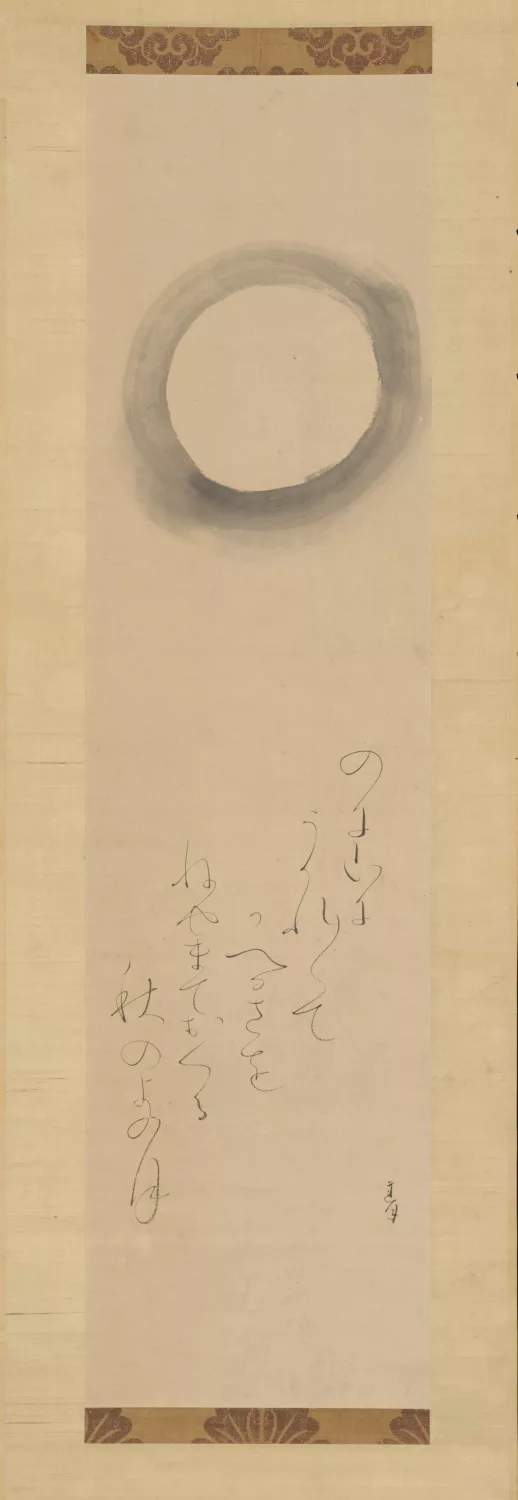

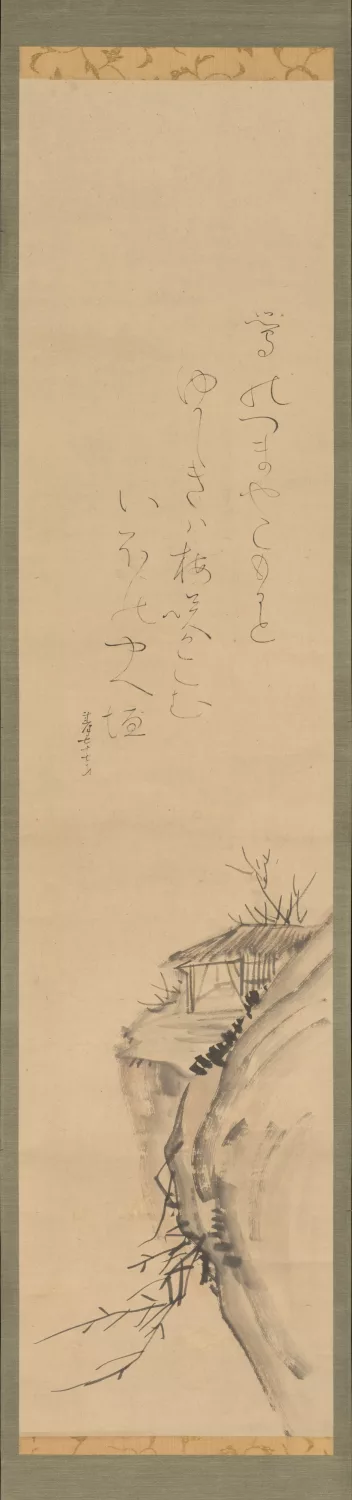

As a child, Rengetsu lived at Kameyama Castle just outside of Kyoto as a lady-in-waiting, where she received education in literature, martial arts, the game of go and other upper-class activities. It is thought that her time at Kameyama was arranged jointly by her biological father and adoptive family, all of whom would have wanted her to receive an education befitting a young woman of noble lineage. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun after the death of her second husband when she was just thirty-three years old, adopting the religious name Rengetsu [Lotus Moon]. After the death of her father and last remaining children, she reinvented herself as an artist, selling quickly made ceramics decorated with her waka poems such as Hanging Flower Vase in the Shape of a Hechima Gourd (1800s), to make a modest living. She also often made works on paper which included her poetry, such as Moon, Blossoming Cherry and Poem (1867).

Rengetsu was best known during her lifetime as a poet, calligrapher and ceramist, and she appeared in multiple issues of the Who’s Who of Old Kyoto (Heian jinbutsu shi) publication series in the late 1830s for waka and painting. Her fluid calligraphic hand was informed by women’s writing of the Heian period (794–1185), and her poetic voice was especially influenced by the poets Ozawa Roan (1723–1801) and Kagawa Kageki (1768–1843). Her writing fused longstanding waka motifs with simple and direct ruminations on personal experience. Her choice to decorate her ceramics with her own waka in easily understood Japanese rather than the more typical scholarly Chinese proved popular, and it is said that at the height of her popularity every household in Kyoto had at least one piece of Rengetsu ware.

Rengetsu influenced and collaborated with a diverse range of artists, writers and intellectuals throughout her life, most notably the literati painter Tomioka Tessai (1836/37–1924), who became her live-in assistant in his youth, and the potter Kuroda Kōryō (1823–1895), who took up the title Rengetsu II after her death. Rengetsu especially influenced fellow female artists and writers, both those active during her lifetime, such as the poet-painters Takabatake Shikibu (1785–1881) and Saisho Atsuko (1825–1900), as well as those working in the twentieth century after her death, such as the painter Uemura Shōen (1875–1949), one of her first biographers. Her works and style remain popular today, and imitations of her distinctive calligraphic and ceramic styles have been widespread since her lifetime.

In collaboration with the Denver Art Museum as part of AMIS: AWARE Museum Initiative and Support

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025