Renee Stout

Sloan, Mark, Kevin Young and Andrea Barnwell-Brownlee, Renee Stout: Tales of the Conjure Woman, exh. cat., Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art (in collaboration with Spelman College Museum of Fine Arts and the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art, Hamilton College), Charleston, SC (July 23–October 23, 2016), Charleston, Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, 2016

→Owen-Workman, Michelle A. and Stephen Bennett Phillip, Readers, Advisors and Storefront Churches: A Mid-Career Retrospective, Kansas City, UMKC Belger Center for Creative Studies, 2002

→Berns, Marla C. and George Lipsitz, Dear Robert, I’ll See You at the Crossroads: A Project by Renee Stout, exh. cat, The University Art Museum – University of California, Santa Barbara (10 January–26 February 1995), Santa Barbara, The University Art Museum – University of California, 1995

Renee Stout: Navigating the Abyss, Marc Straus Gallery, New York, January 8 – March 5, 2023

→Renee Stout: Tales of the Conjure Woman, Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art (in collaboration with Spelman College Museum of Fine Arts and the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art, Hamilton College), Charleston, SC, July 23 – October 23, 2016

→Astonishment and Power: Kongo Minkisi and the Art of Renee Stout, The National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 1993

African-American artist working in assemblage, installation, mixed-media sculpture and painting.

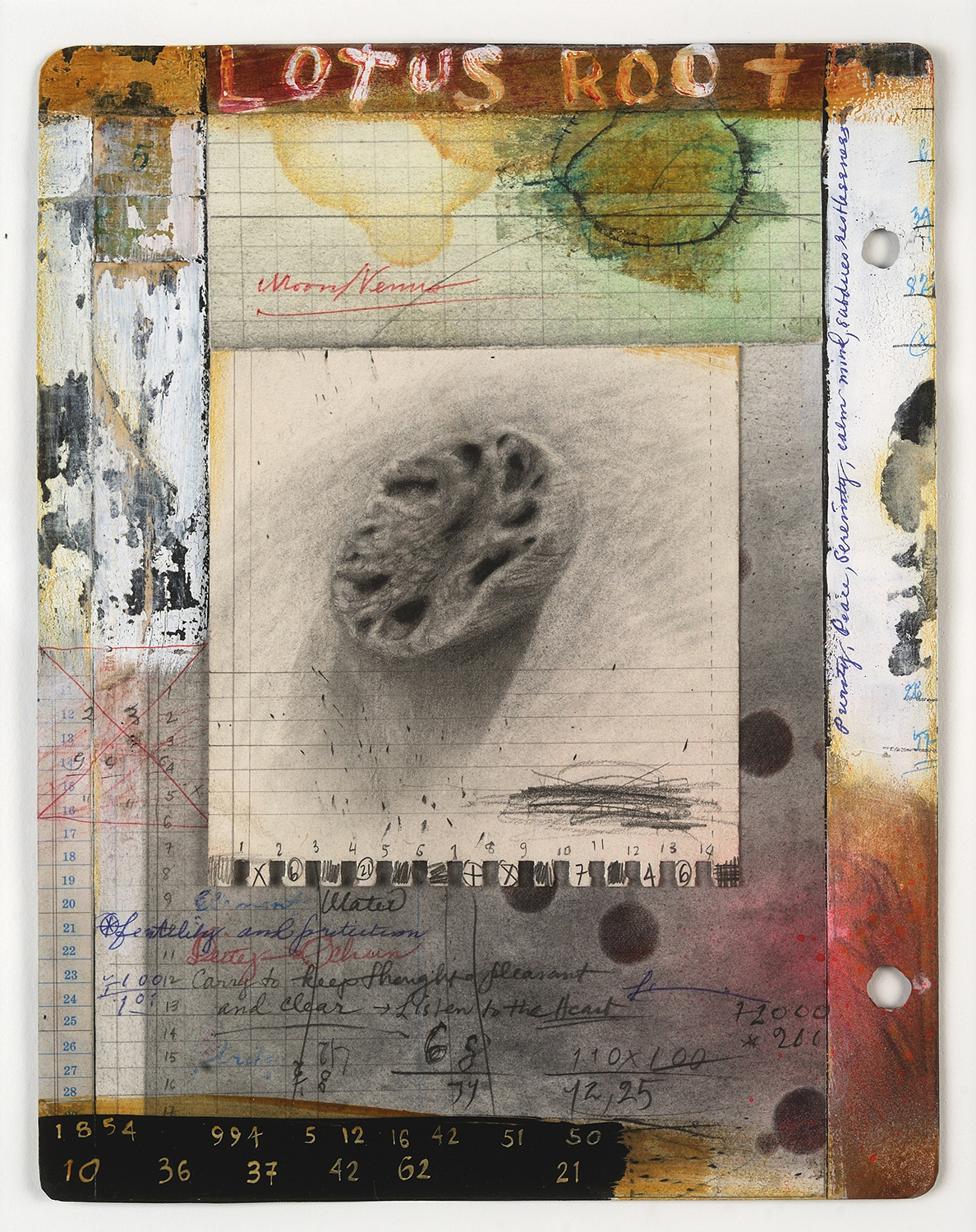

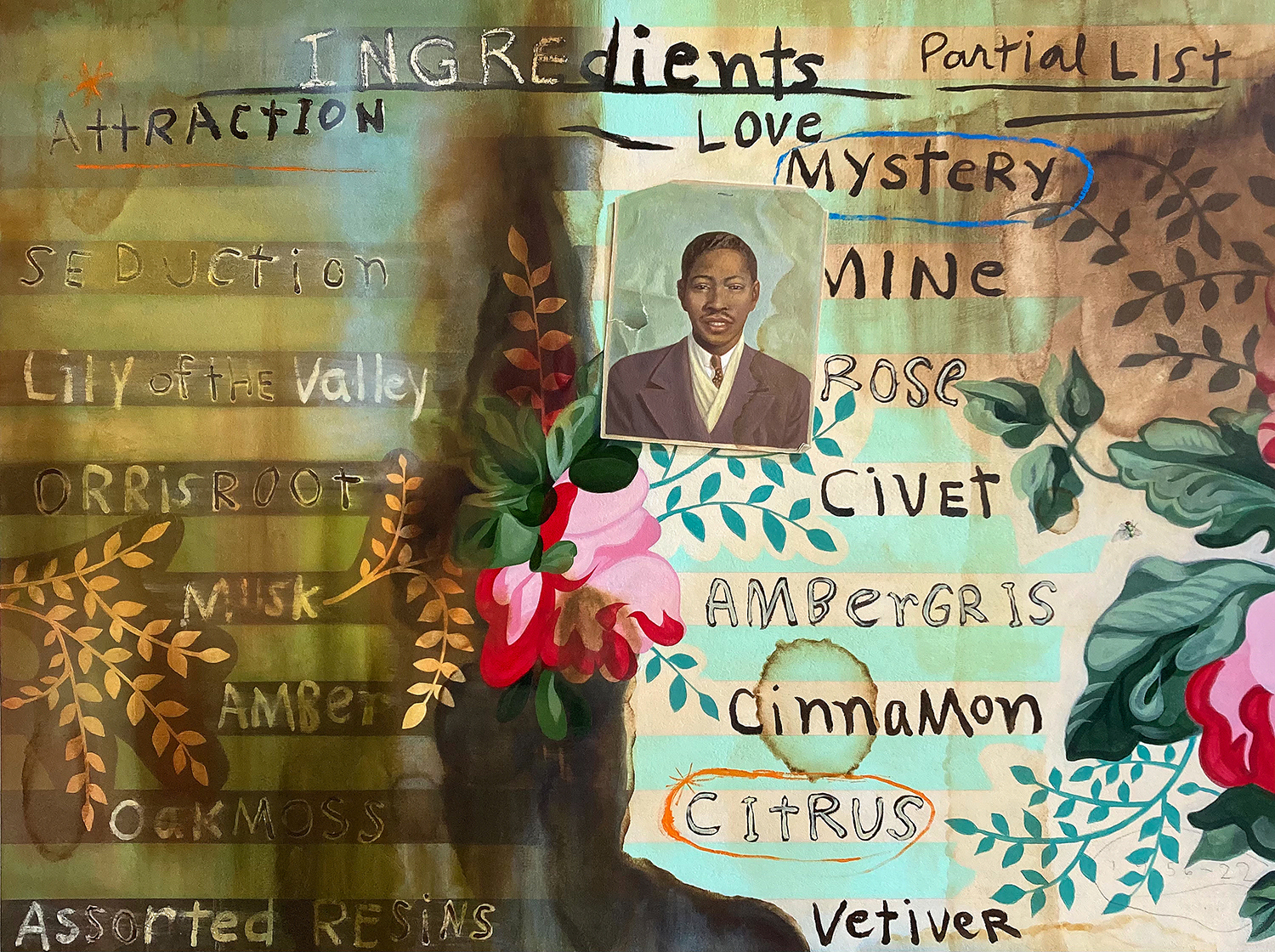

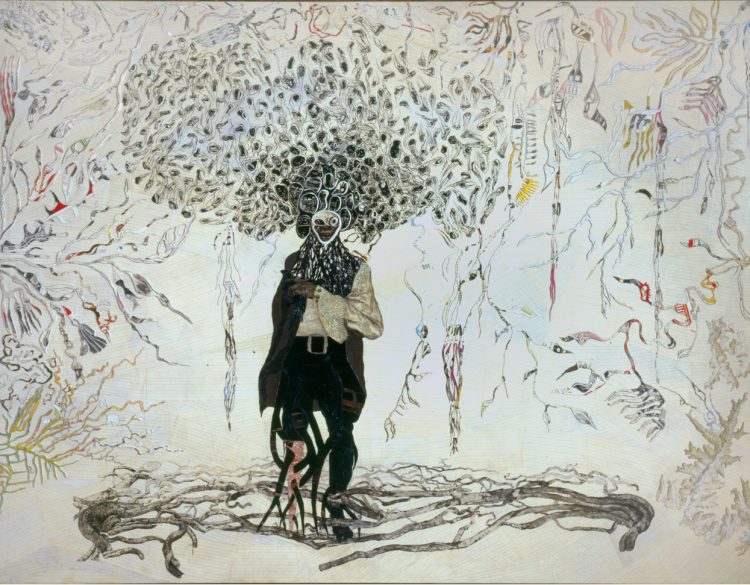

Renee Stout’s large body of work is deeply rooted in her spiritual, social and political quest. Through a variety of mediums and materials, her practice centres on the continuous excavation and regeneration of spiritual ancestries, and a subjective, detailed and sensorial investigation into the many cultures of the African diasporas in the United States. Thorough her practice, R. Stout seeks real and speculative legacies of African American magic as methods of healing, and resistance. In her installations, mixed-media sculptures and assemblages, she invokes the sacred through found objects, and as a painter she sometimes embodies fictional characters to tell stories of Hoodoo, a figure both protective and mischievous. As she states, it is a process “both cathartic and empowering”.

Growing up in a working-class household in Pittsburgh, R. Stout regularly attended a drawing class for children at the Carnegie Museum of Art. In its African Art section, she encountered a Kongolese Nkisi Nkondi. Although the object was poorly documented and generically labeled as “fetish”, the ten-year-old R. Stout was enchanted by the work, which combines sculpture, amulet and nails. She often speaks of this early encounter as pivotal in her artistic practice.

After graduating from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh with a BFA in painting in 1980, R. Stout was mostly interested in realistic paintings, as shown in one of her earliest pieces, Hanging Out (1983), which depicts four black men sitting serenely in front of a store. In 1984 she was part of Northeastern University in Boston’s African American Master Artist-in-Residency Program, before moving to Washington, DC in 1985. These two years mark a transition from photorealistic painting to a more conceptual approach, where an introspective R. Stout first experimented with the construction of simple boxes, before moving towards a process of collecting found and natural objects, growing further interested in artists such as Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) and Betye Saar (b. 1926).

Between 1984 and 1985 the impression of that first nkisi nkondi becomes more evident, leading to what would become R. Stout’s “fetish series”, first shown in the 1989 exhibition Black Art: Ancestral Legacy: The African Impulse in African-American Art at the Dallas Museum of Art. The show featured Fetish #2 (1988), a life-sized plaster cast sculpture made from the artist’s own body using shells for eyes, with elements hinting at her family history: found objects, hair and nails as direct references to the Nkisi Nkondi. In 1993, with Astonishment and Power, she would become the first American artist to have their work shown at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, where sculptures such as Power Object (Homage to Joseph Cornell) (1991) and Headstone for Marie Laveau (1990), were shown alongside genuine Kongo Minkisis.

This national recognition meant R. Stout’s work was considered within the exclusive framework of the “African impulse”, while today it is her affinity with artists like Cindy Sherman (b. 1951) and Sherrie Levine (b. 1947) and their appropriations of pre-existing images that is more highlighted. Indeed her series Fetish and sculptures of Astonishment and Power do not aim at duplicating the spiritual capacities of Nkisi power figures as much as they use the conventions of ethnographic display in a sly attempt to invoke ghosts of unresolved histories. The same process guides her use of fictional alter-egos, hoodoopractitioners Madame Ching and Fatima Mayfield – for whom she has designed a Rootworkers’s Table (2011), as well as a storefront neon sign – that allowed her to explore the formal, conceptual and aesthetic healing powers of rootwork in the present. More recently, R. Stout has returned to painting as a way of plotting escape plans to a parallel universe where justice and Hoodoo Assassins (2020+) rule.

She is a recipient of many prizes and awards, amongst them the Women’s Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award (2018).

A biography produced as part of “The Origin of Others. Rewriting Art History in the Americas, 19th Century – Today” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023