Toyen (Marie Čerminová dite)

Bischof Rita, Toyen : das malerische Werk, Frankfurt am Main, Neue Kritik, 1987

→Caille Françoise, De l’artificialisme au surréalisme : Štyrský et Toyen (1926-1934), thesis directed by José Vovelle, Lille, 2001

Toyen. L’écart absolu, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, March 25 – July 24, 2022

→Toyen : une femme surréaliste, Musée d’Art moderne, Saint-Étienne, 28 June – 30 September 2002

→Toyen, Moderna museet, Stockholm, 24 August – 06 November 1985

Czech Painter.

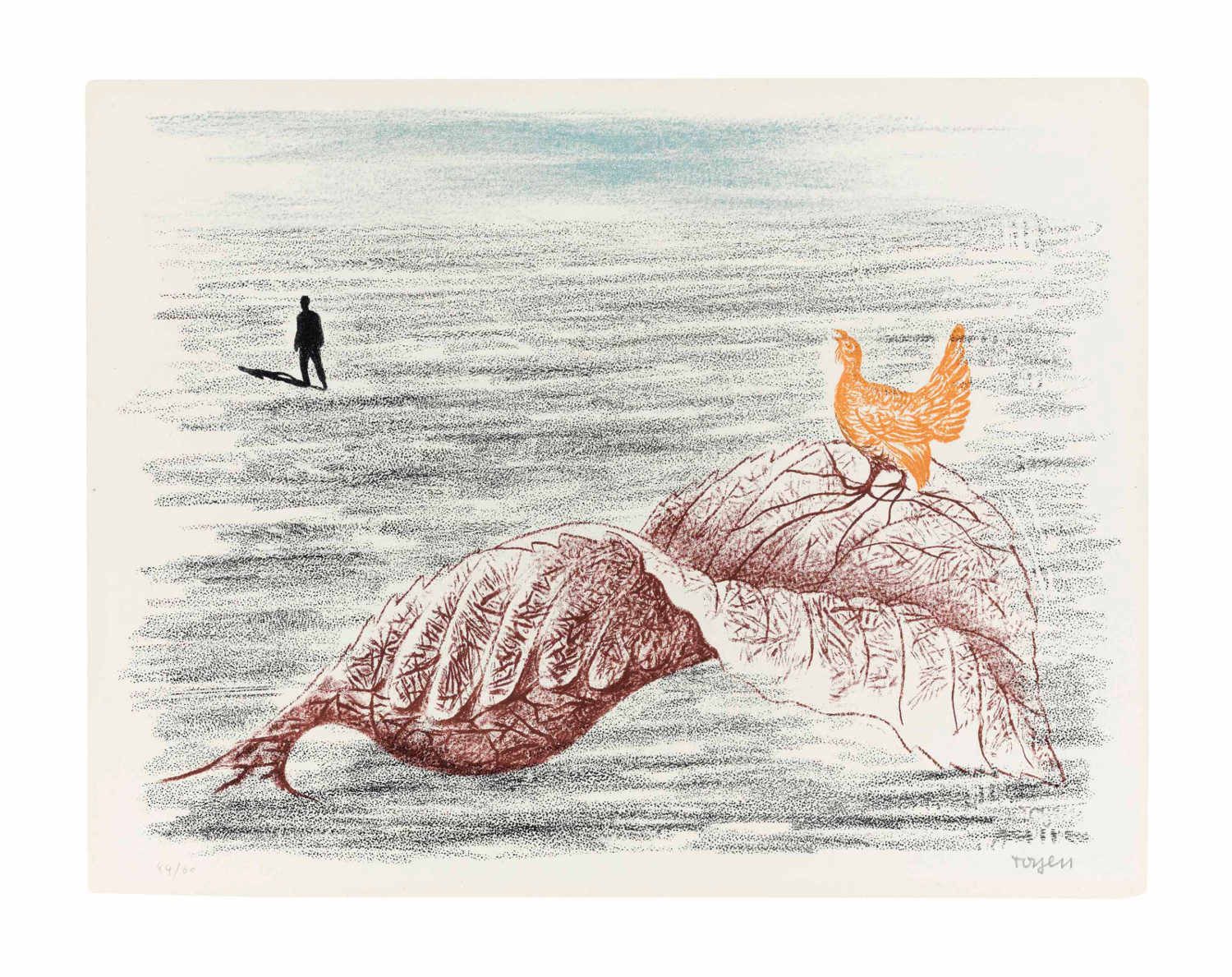

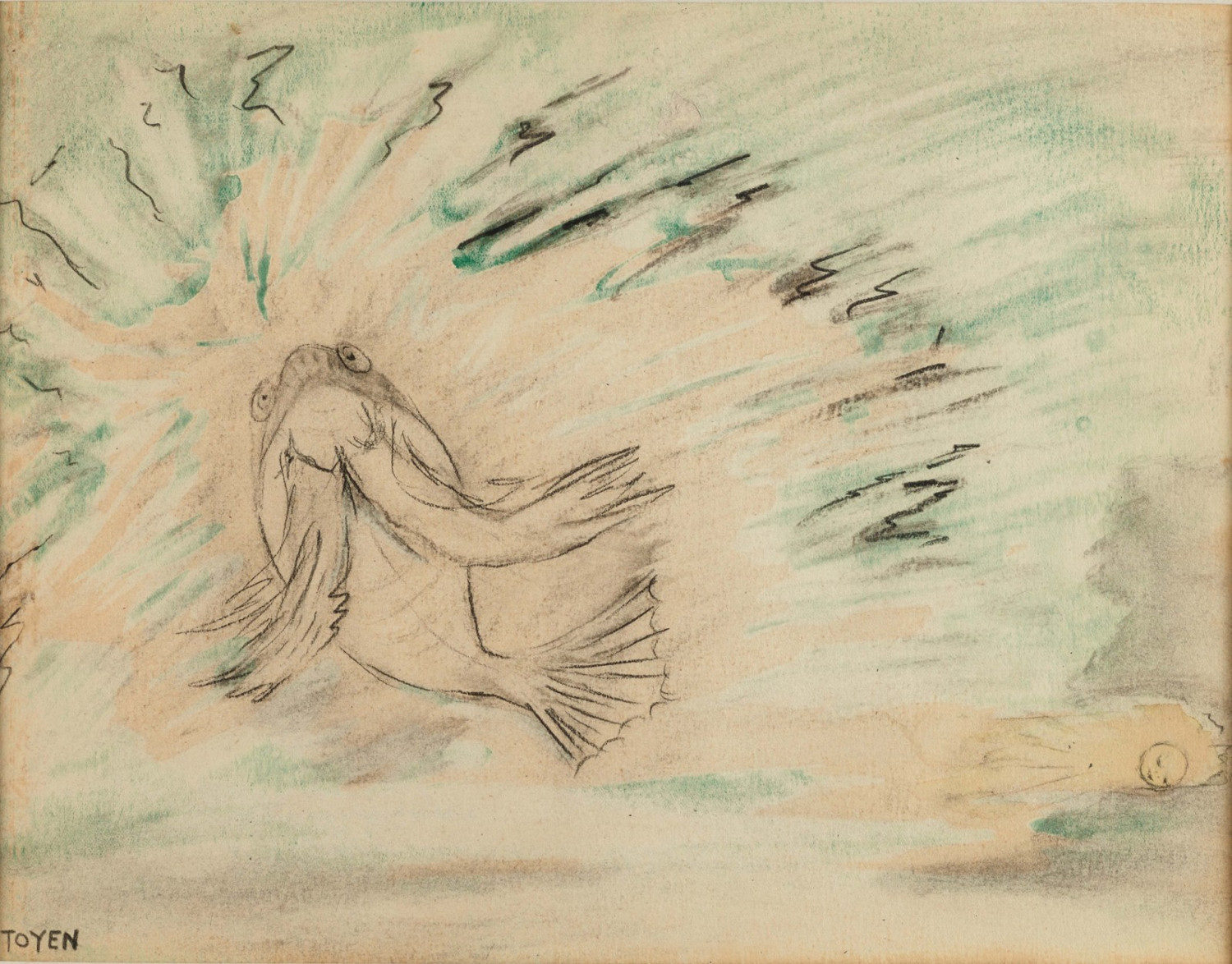

A dominant figure in Czech surrealism, Toyen spent her life between Prague, where she worked in a tight-knit union with Jindřich Štyrský, and Paris, where she finally went to live with Jindřich Heisler in 1947. Although she would hold, alongside André Breton, an important place in the Paris Surrealist movement of the 1950s, she nonetheless followed an individual path – a path of uncompromising poetry. Breaking with her fellow painters from a very early age, she joined in 1923 the avant-garde Prague “poetist” group Devětsil, leading to her abandonment of the Cubism of her early days in favour of a sort of lyrical abstraction. It was at this time that she created, along with Štyrský “artificialism”, a mode of art that used painting to inspire “poetic emotions that are not only optical, to stir a sensitivity that is not only visual”. This search for an emotional impact – one created by the coloured surfaces – drove both artists to bring forth from their subconscious concrete impressions that are not directly identifiable and that stem from desire, fear, or other deep, obscure forces: arachnoid curves, trails of smoke, uncertain shapes bathed in subdued light that gradually take over the canvas. Fusion with the Surrealist movement was of the essence: in March 1934, with Štyrský and other artists, including poets Karel Teige and Václav Nezval, she founded the Czech Surrealist movement. The bonds created with the French movement as of 1933 became stronger still when André Breton and Paul Éluard came to Prague, a town they enthusiastically called “the magical capital of old Europe” (Breton), and, at that precise time (April 1935), “the door to Moscow” (Éluard). Henceforth, Toyen’s works were fully surrealist. Her dreamlike paintings showed ghostly, nocturnal spaces – those of a mental prehistory – with floating, enigmatic objects – a mix of déjà-vu and the unreal – which mainly belong to a mineral world (shells, eggs, crystals, stones), references to the human body (eyeballs), as well as unlikely and often monstrous shapes arising from intimate hallucinations. This is a world of abandoned things, hollowed larvae, latent forms bathed in a morbid light, deeply melancholic but always extremely raw: the painter’s visual imagination possessed the acuteness and veracity of dreams (Traumatisme de la naissance, 1936).

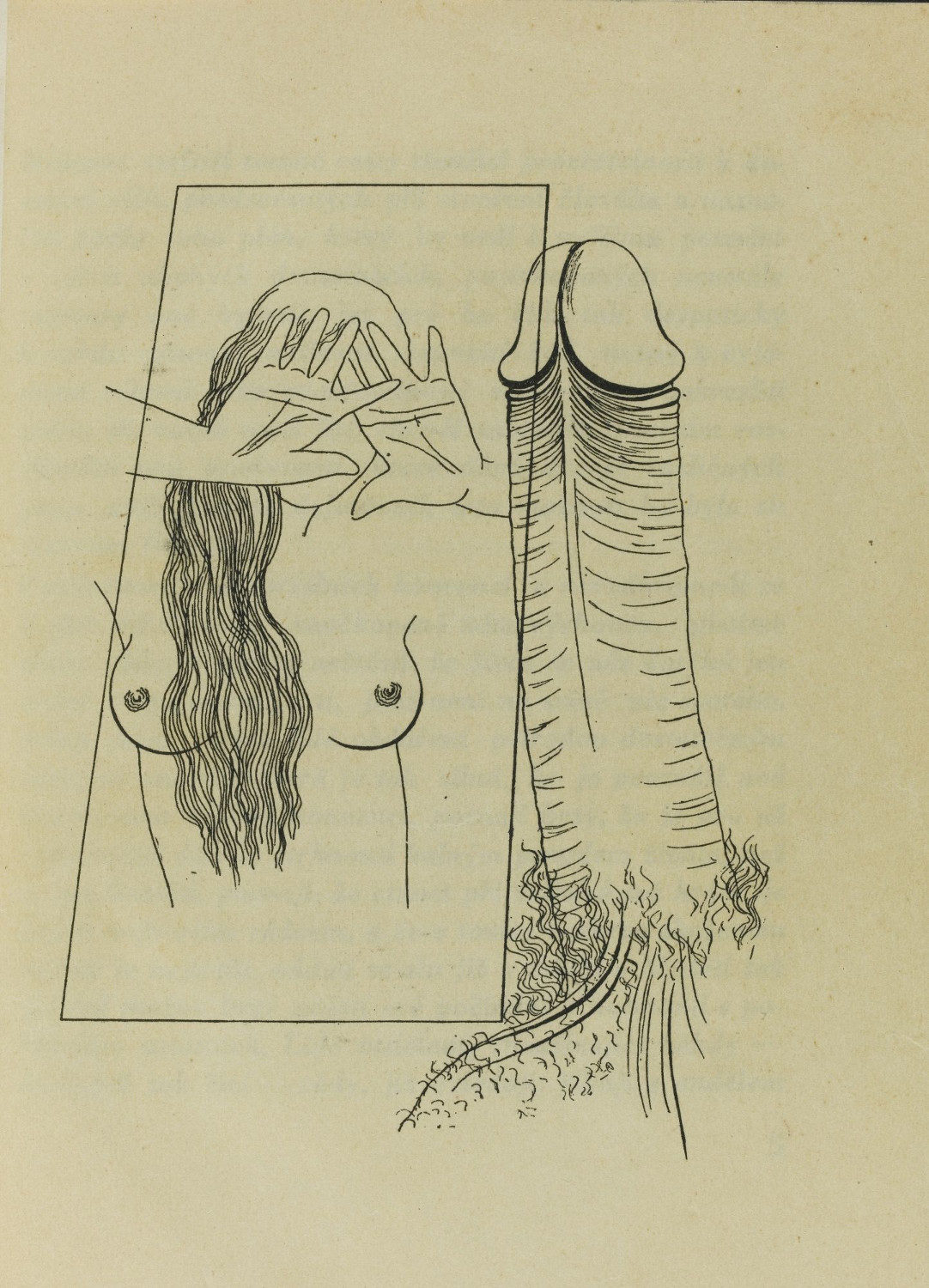

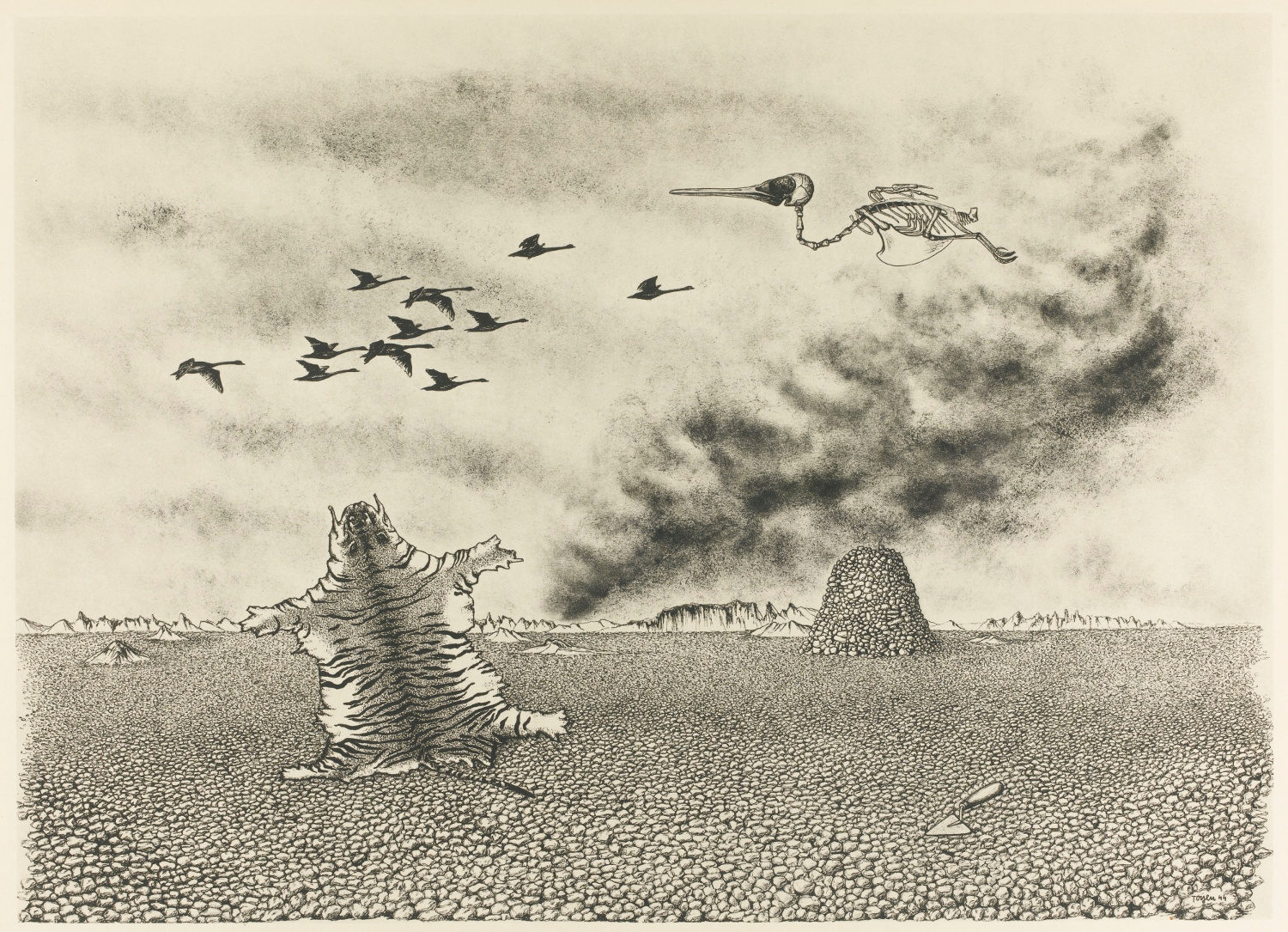

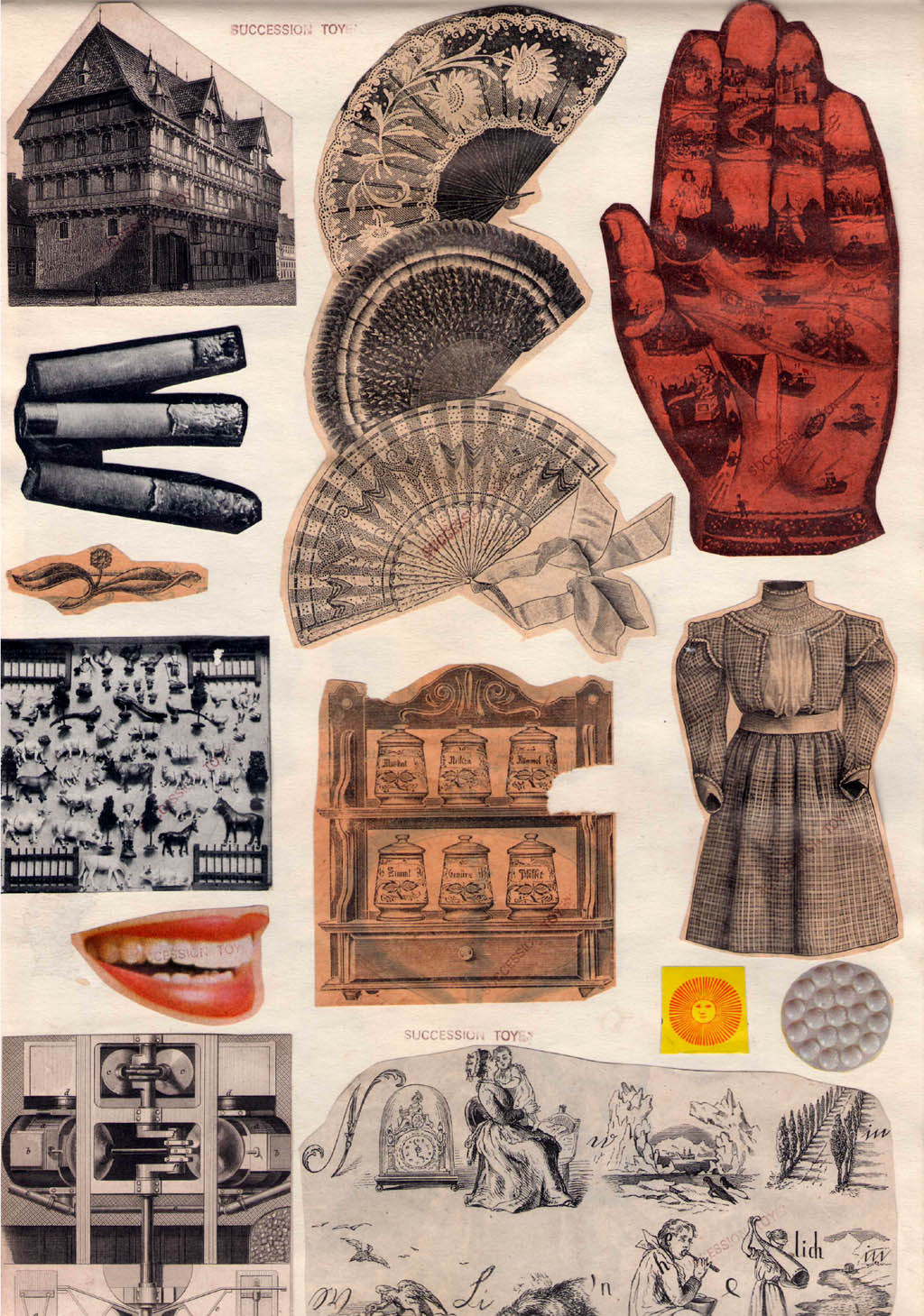

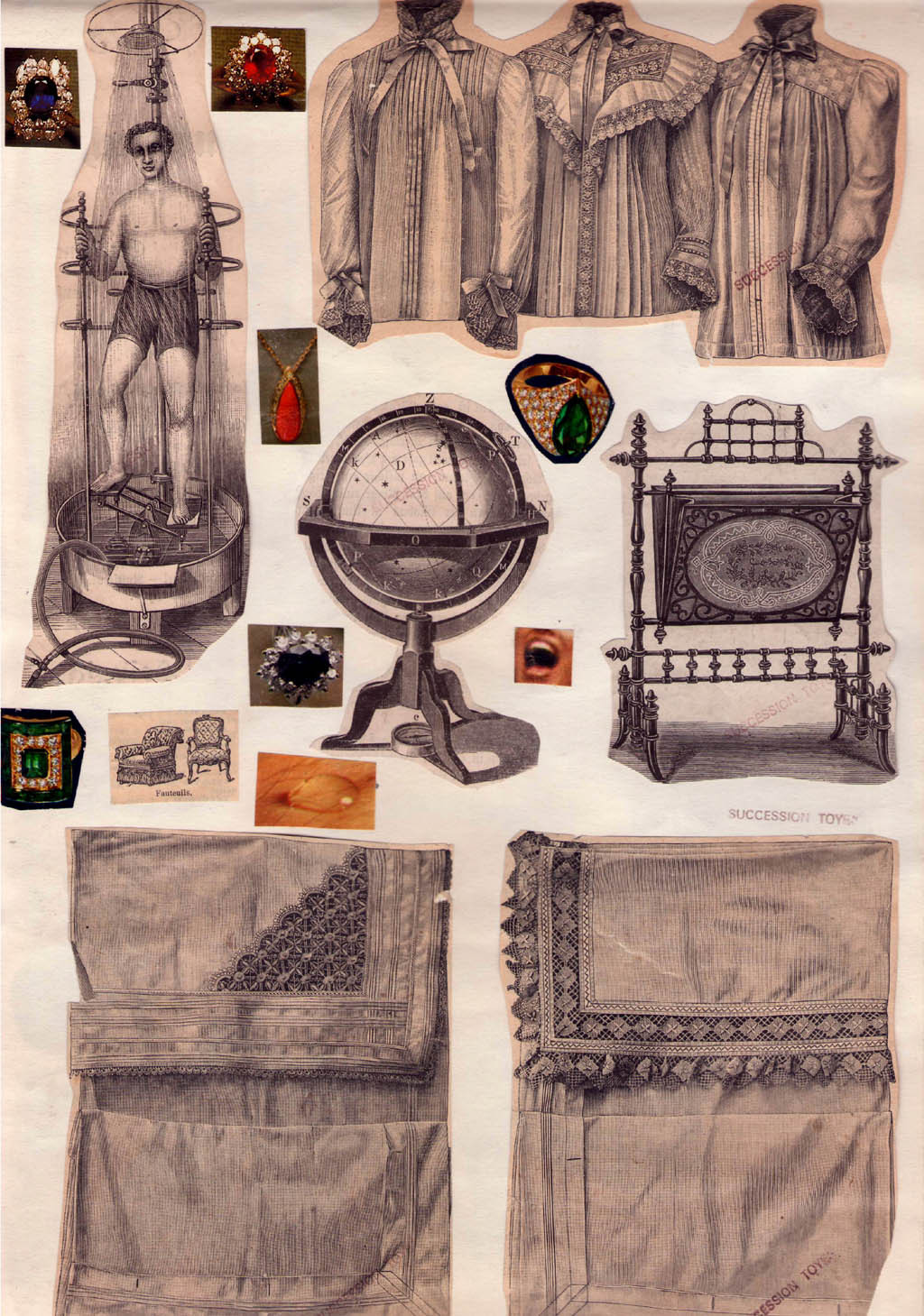

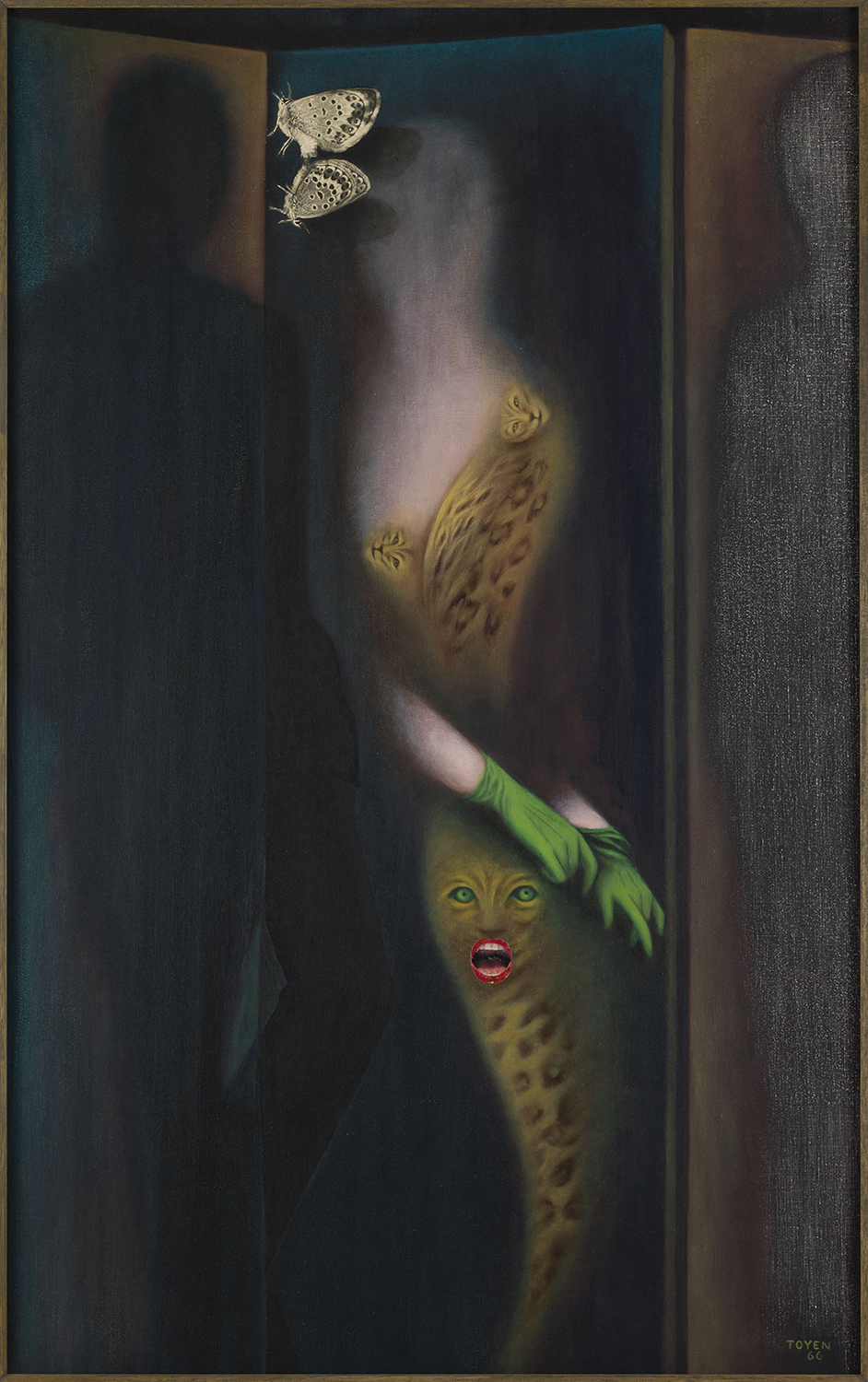

In the years leading up to and during the Second World War, Toyen hardly painted at all. Like those by Goya, her anguished ink drawings and collages violently presaged and denounced horror and cruelty (Les Spectres des déserts, 1937-1938). At the end of the war, her morbid landscapes of disaster and desolation barely opened onto a glimmer of hope: carnivorous butterflies rain down on a field of graves in L’Avant-Printemps (1945); a voluptuous feline prowls among the poisonous flowers in Au château Lacoste (1946). Even in her state of despair and reproach, she clung to her faith in a dreamlike life, and in the strength of poetry in the face of evil forces (Cache-toi guerre !, 1947). Carried out in Paris in great moral isolation – in spite of the way they were received by her surrealist friends – Toyen’s last works, which delved further into the intimate world of Eros, would maintain an unnerved, anguished aspect to the very end. As in a dream, her painting was a terrain that brought together a disparate mix of elements, to be seen as indecipherable riddles: gloves, dresses, hair, ovoid shapes, and eyes populate her visions, in which desire and anguish bring to mind more defined, animal sexual impulses – the figure of the cat represents a sort of archetype of the female sex. Carried out with a goldsmith’s precision reminiscent of that of Yves Tanguy, her forms at once caressing and aggressive, her materials both hard as bark and velvety as skin are of an ultimately sensual poetry. The effect of puzzlement and menace inherent in her visions, bathed in artificial light, instils a certain power of enchantment. Toyen’s paintings are magical, containing medium-like powers: in a final series of nostalgic paintings, she introduces into her visual dreams the world of alchemy inherited from old Prague, a world of secret symbols inscribed on old heraldic insignia.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Toyen : Subversive Baroness of Surrealism | ARTE (French)

Toyen : Subversive Baroness of Surrealism | ARTE (French)