Zoe Leonard

Lebovici Élisabeth, Zoe Leonard, exh. cat., Centre National de la Photographie, Paris (9 September–2 November 1998), Paris, Centre National de la Photographie, 1998

→Geldin Sheri (ed.), Analogue / Zoe Leonard, exh. cat., Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus (12 May–12 August 2007), Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2007

Zoe Leonard: Photographs, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Zurich; Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, 2007–2009

American photographer, multimedia artist and activist.

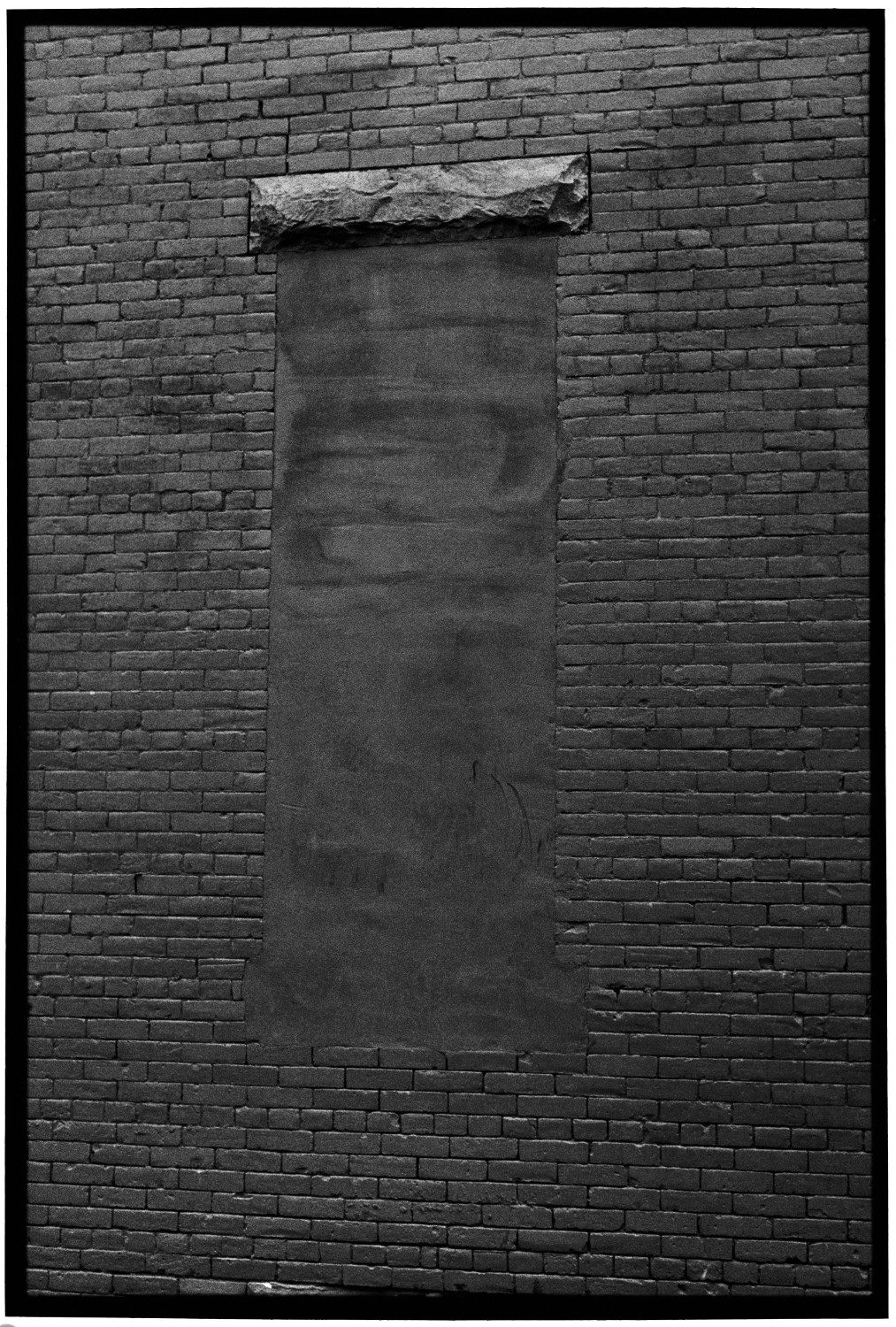

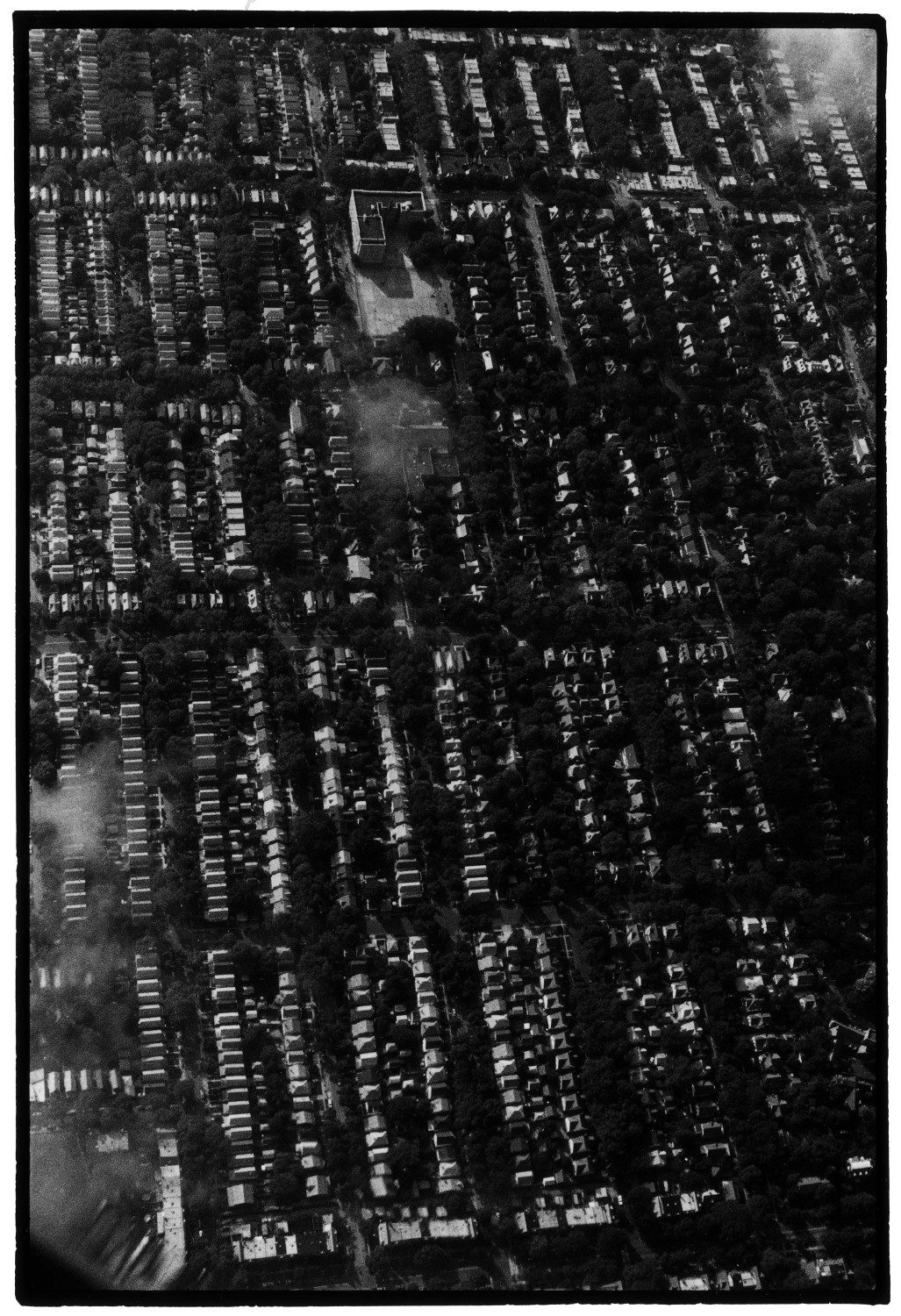

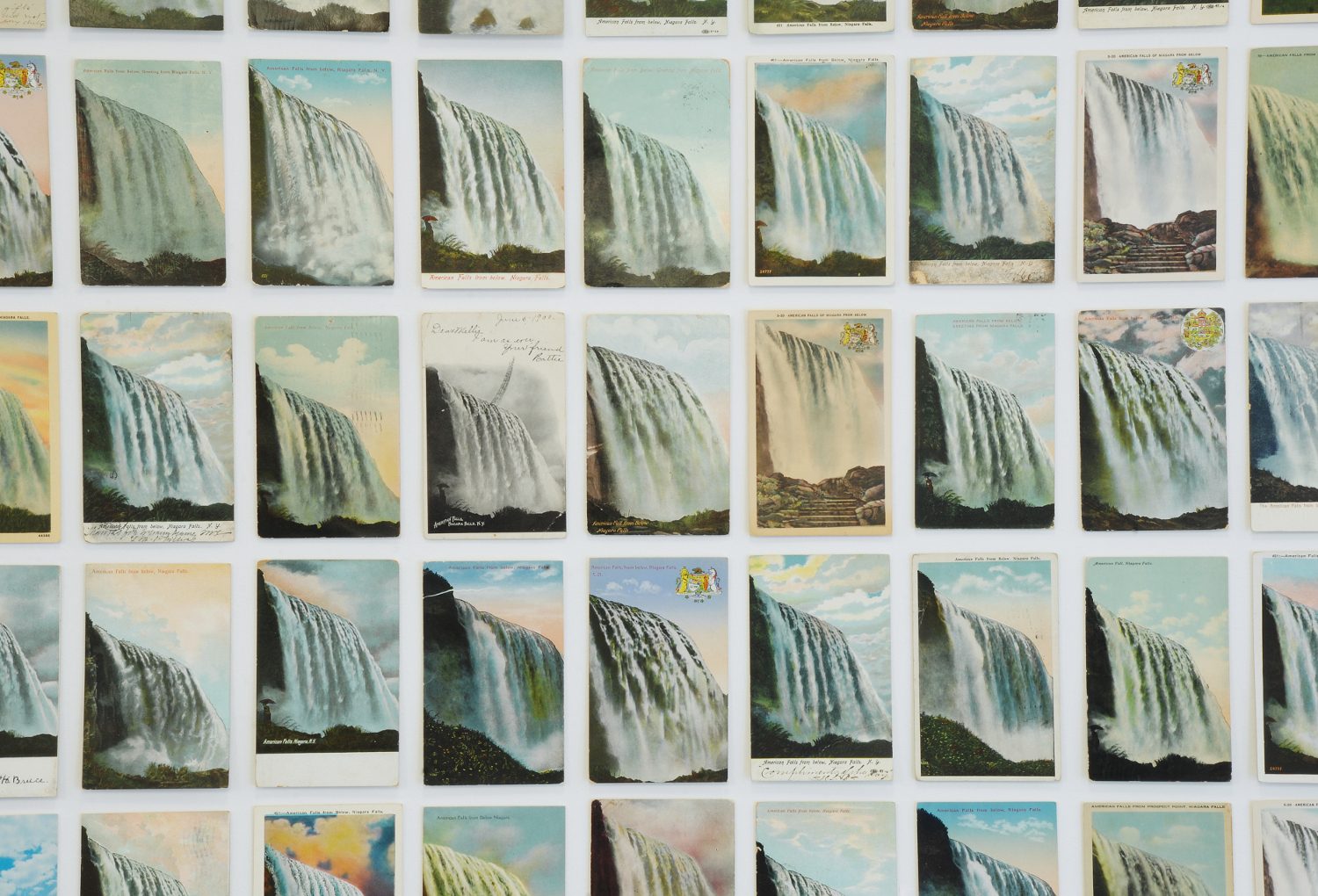

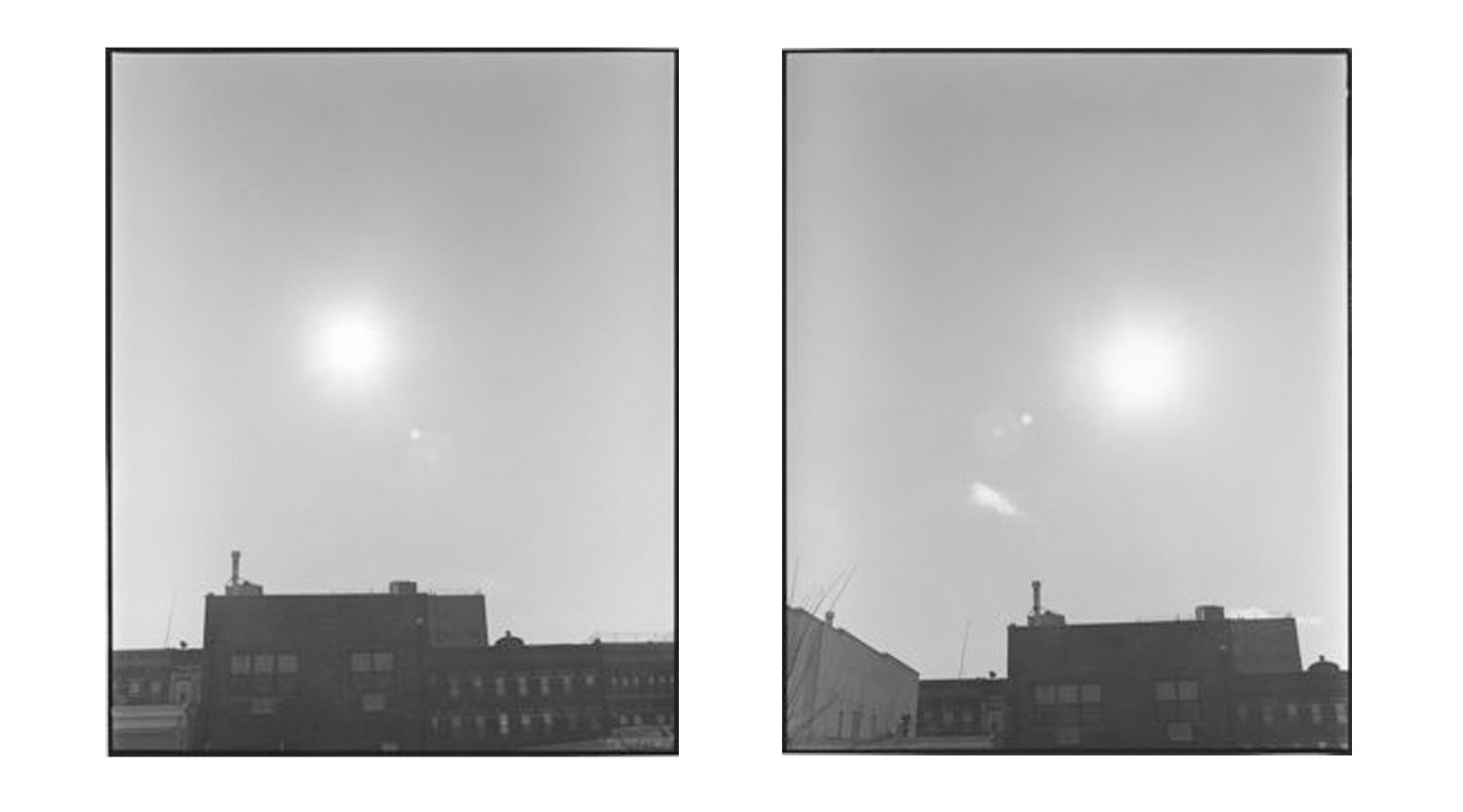

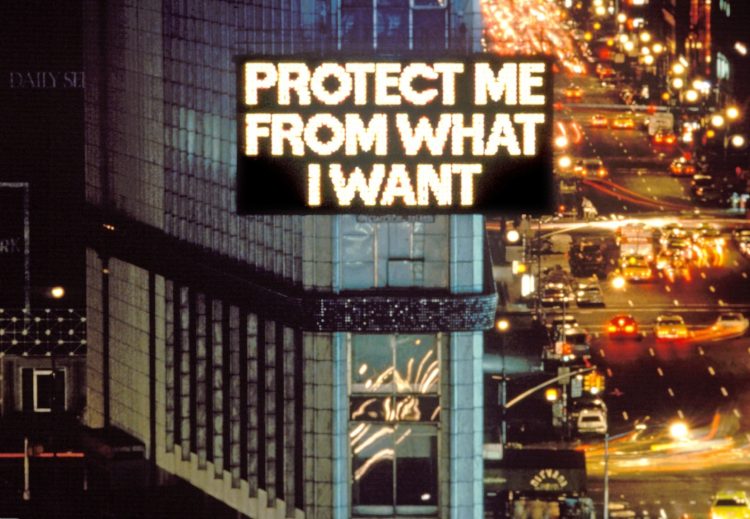

A self-taught artist, Zoe Leonard experimented with both photography and activism. By the early 1980’s, instead of practicing conceptual photography which at that point thanks to technological advances and new pictorial formats rivaled painting, she was drawn to the form and texture of the gelatin silver process, to which she brought the utmost care, often using long exposure times after taking the shot. Her first photographs, of clouds taken through an airplane window (Untitled, 1989), railways (Aerial Untitled, 1986), waterfalls (Niagara Falls, 1986-1991), unfolded city maps (Map of Krakow, 1988-1990), as well as her nocturnal cityscapes (Paris, 1986) show apparent signs of accidents, marks and scars of use, including what happens during the creation of the image and the photographic process. For the artist, these small imperfections are the spearhead of resistance to norms—societal, gendered, and sexual. Leonard’s activism within Act Up in New York, but also in multiple lesbian artist groups, including Gang and Fierce Pussy (revived in 2010), created the link between radical action (dramatic public acts, expressing the activists’ anger with various administrations or agencies), and visual representation.

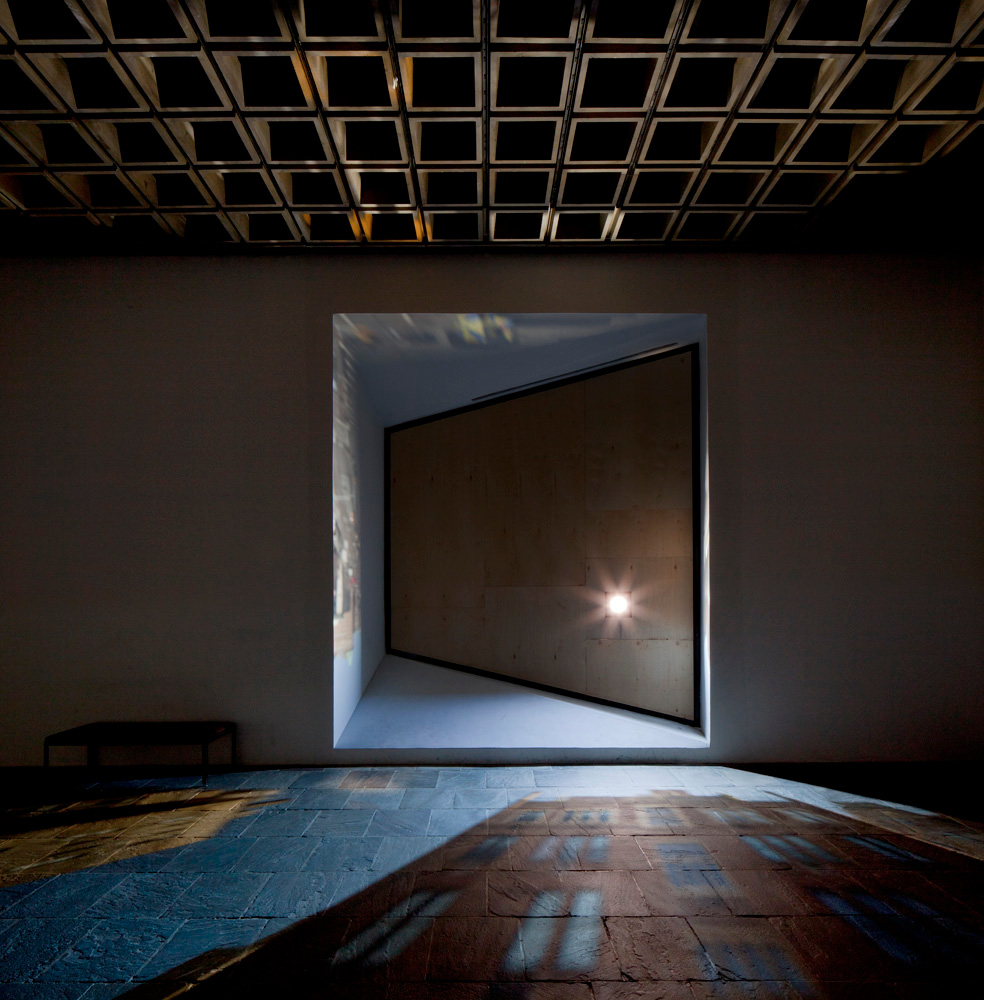

Her images describe social and sexual conventions as so many instruments of control: Chastity Belt 1990-1993 and Beauty Calibrator 1993. Her installation at Documenta 9 in Kassel, Germany in 1992 was one of the high points of her critique: the rooms of the Neue Galerie were emptied of their classical and romantic paintings, except those where women, represented by the male brush, occupied the center of the piece. Meanwhile the vacant places were hung with small, close-up black and white photographs of vulvas—friends of the artist—reversing both typical museum representations and the heterosexual point of view. The installation Strange Fruit (for David) (1992-1997), composed of some 300 fruit peels, sewn and “repaired” with colorful thread and stickers, is dedicated to her friend, the artist David Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS. This piece both reflects the process of the work of mourning and, though purchased by the Philadelphia Museum of Art for its collection, is intended itself to perish one day.

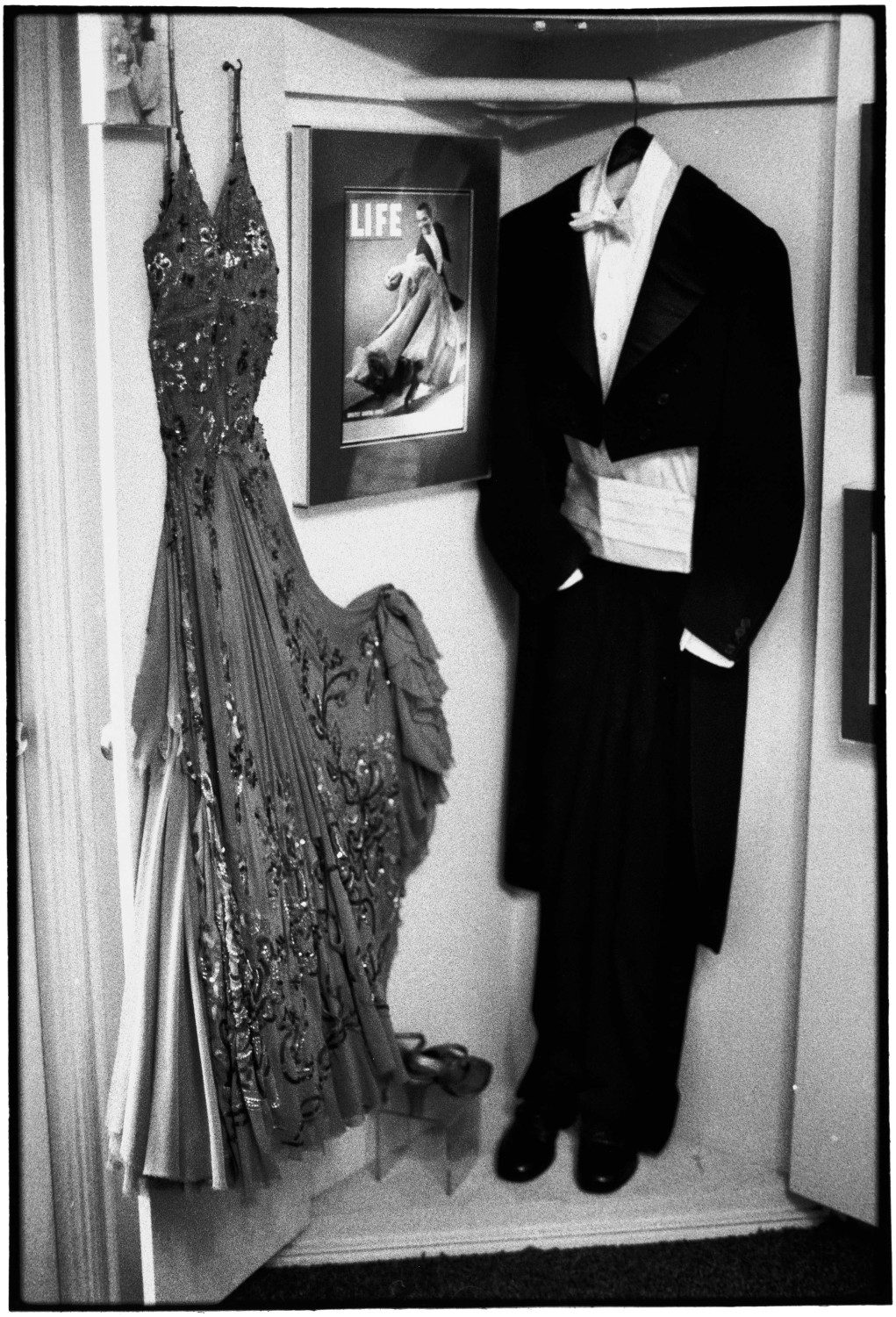

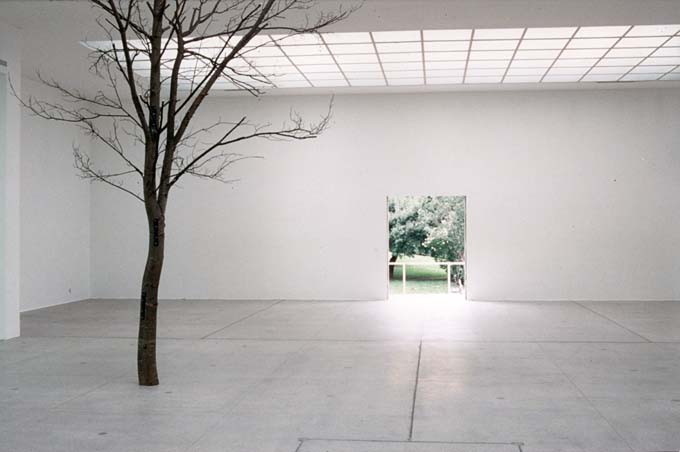

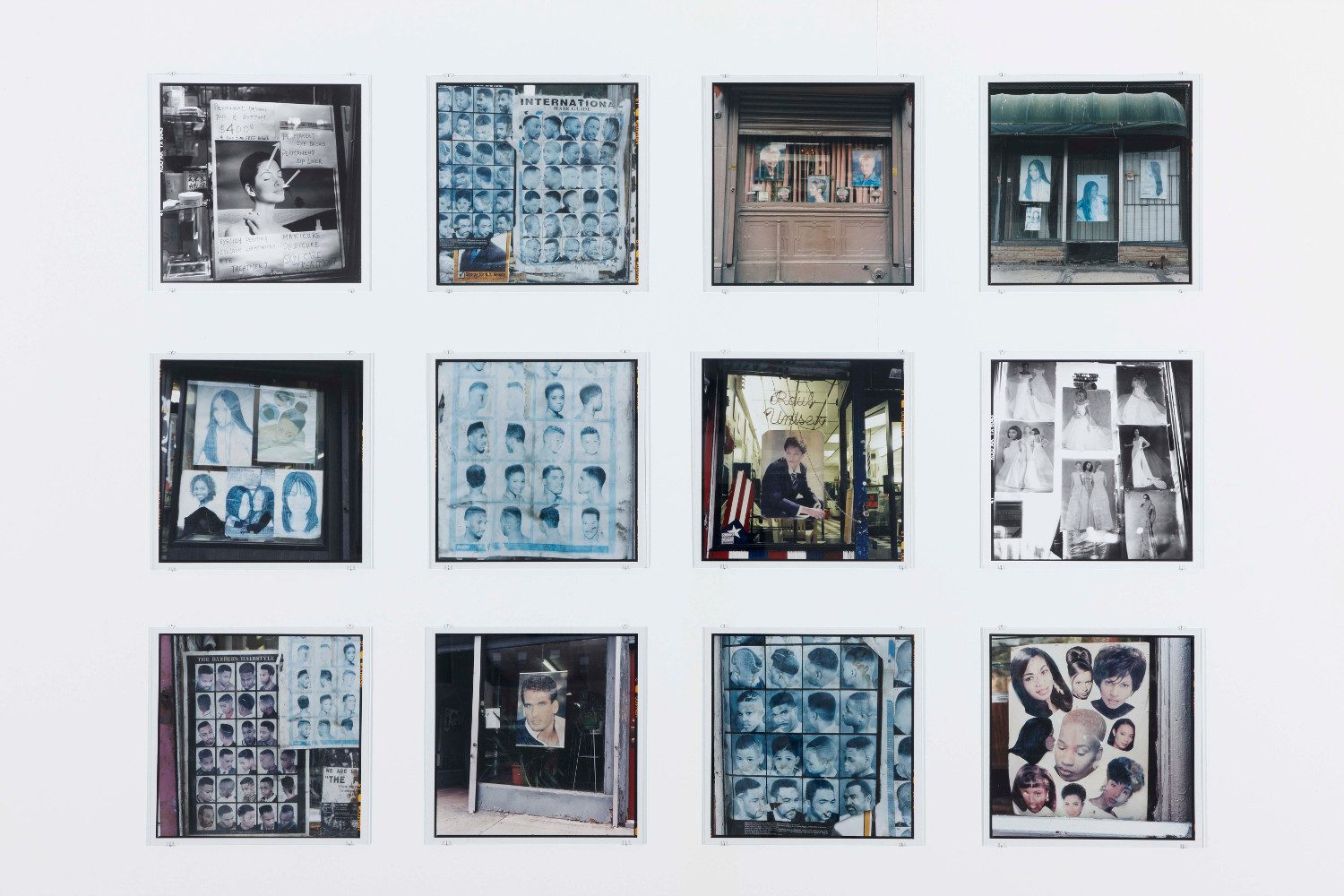

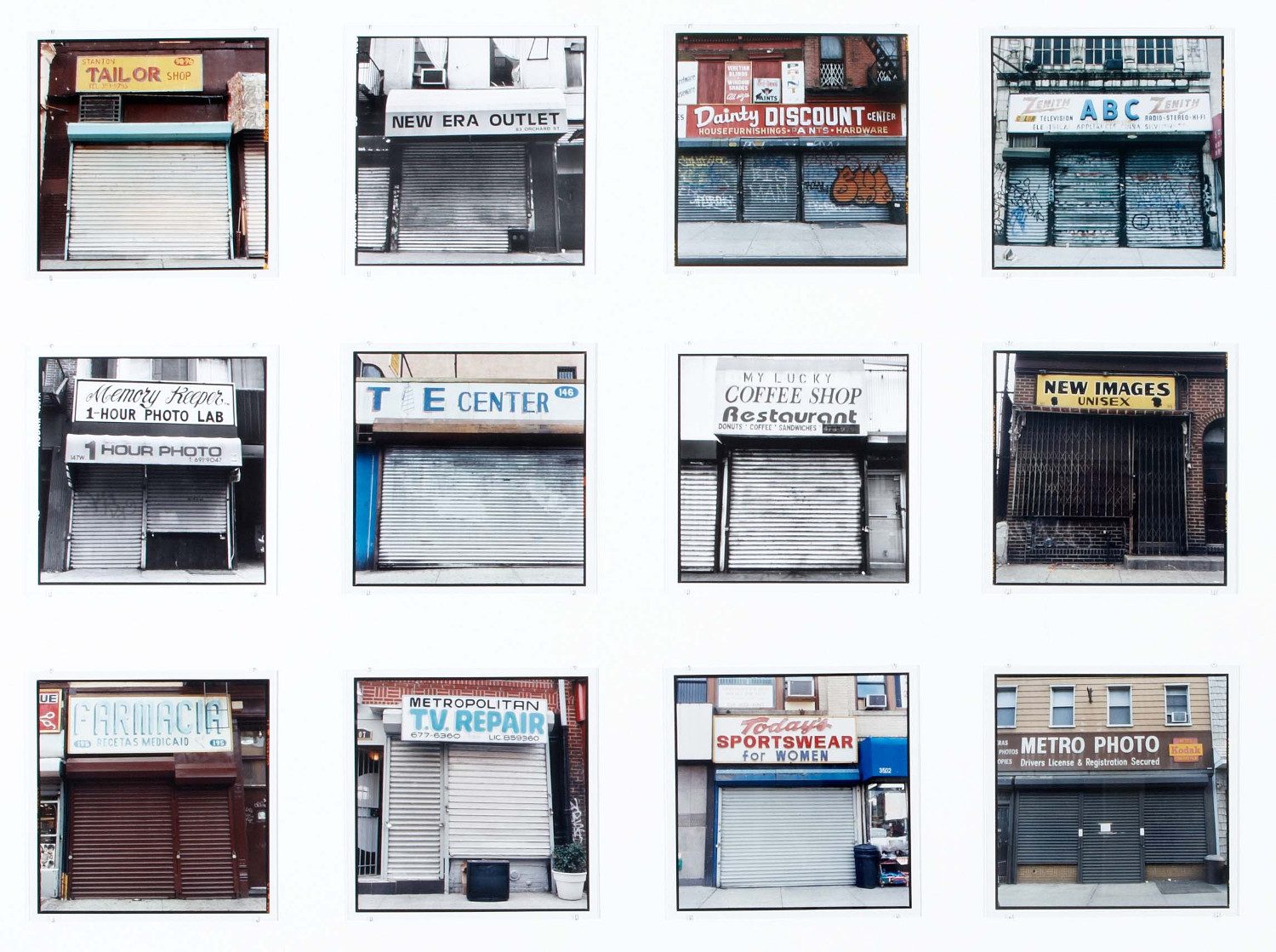

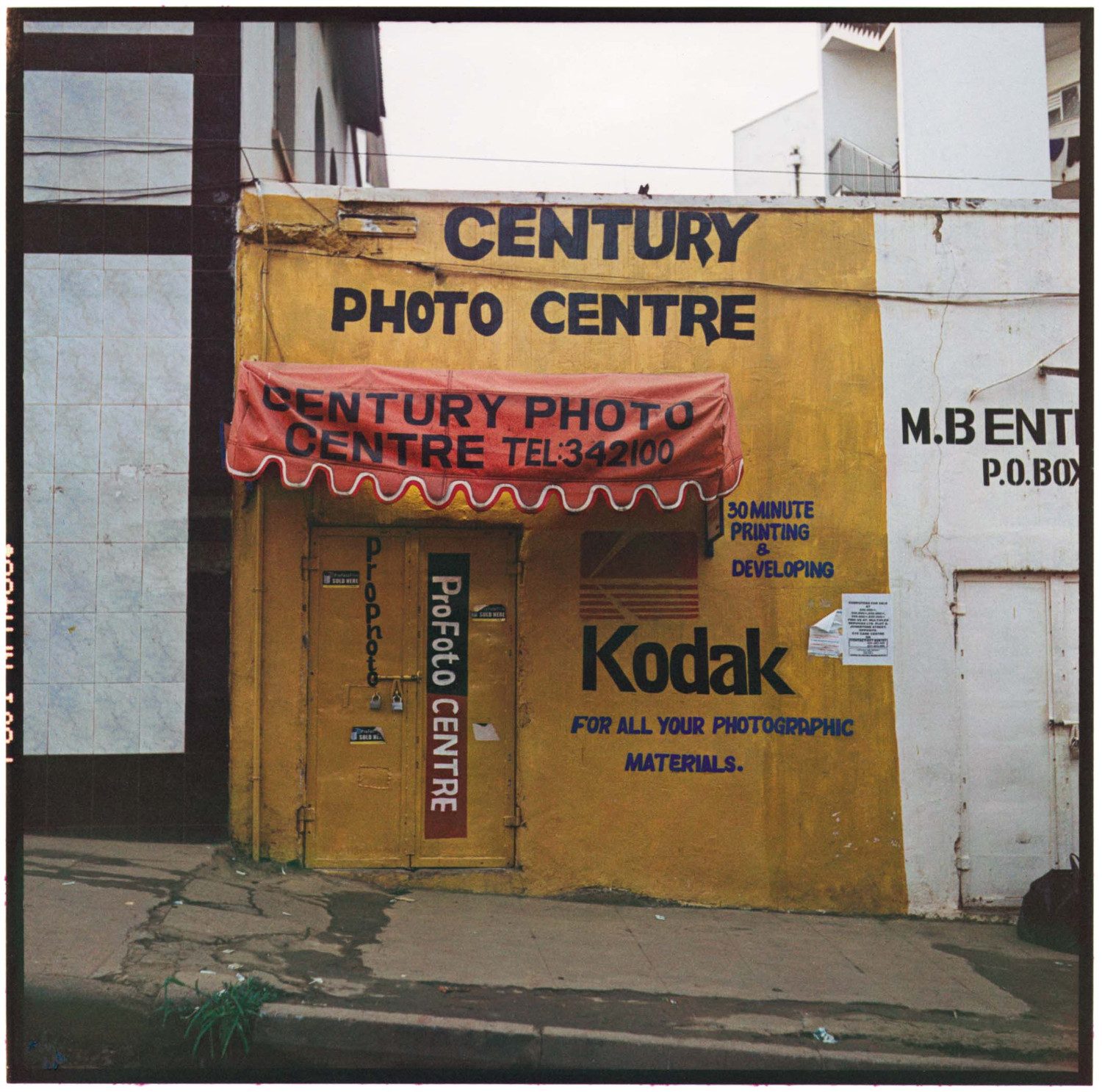

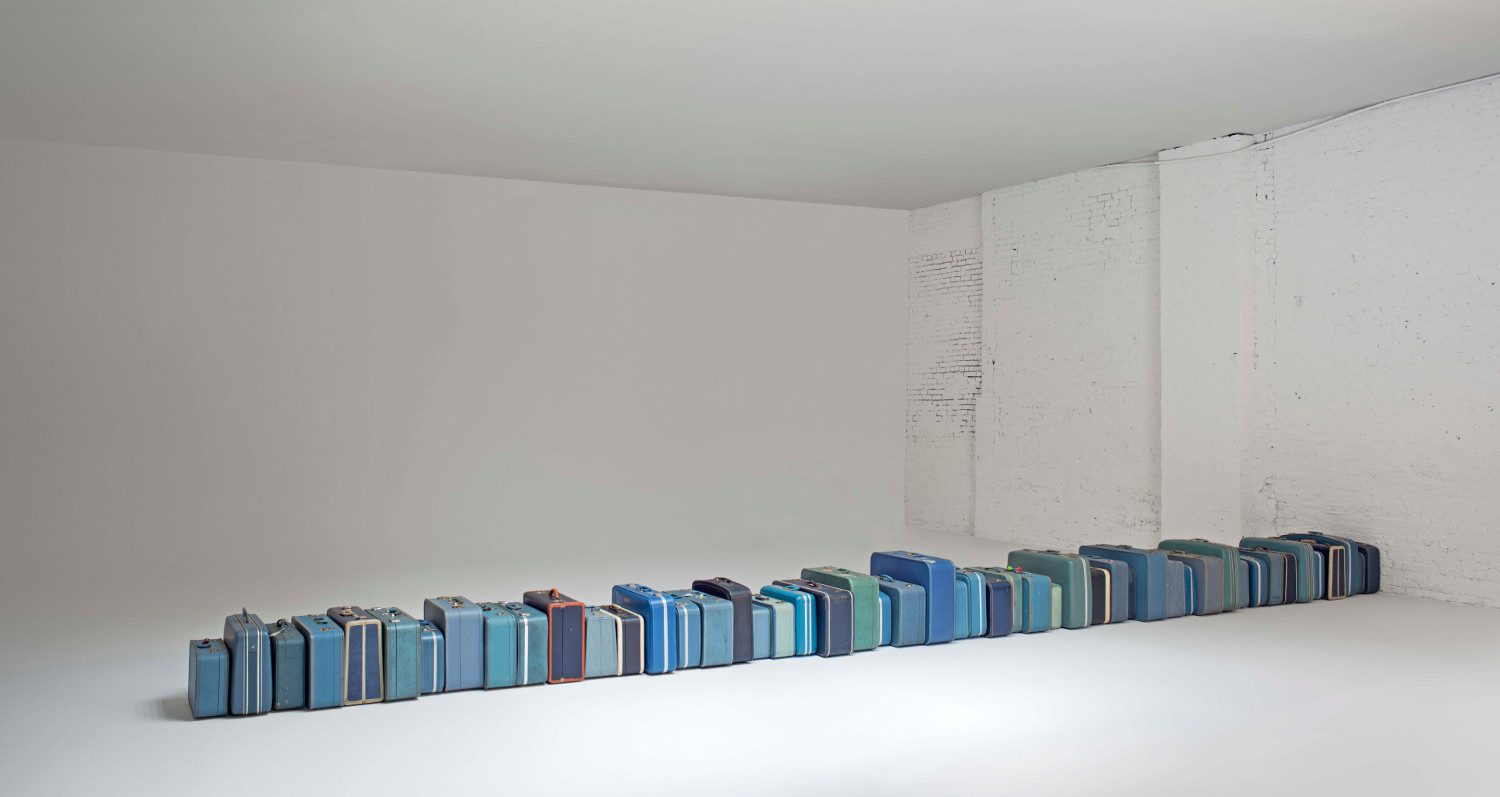

Leonard has also developed a body of sculptural work (reconstituted trees, a disturbing assembly of damaged dolls, stacks of suitcases), and published materials (books of images and quotes, among others.) She also created, from scratch, an important collection of archives documenting the fictional biography of a black, lesbian actress in Hollywood in the 1930s, for the film The Watermelon Woman (1996) by filmmaker Cheryl Dunye. From 1998 to 2007, she embarked on Analog, a vast and poignant project based in her neighborhood, the Lower East Side of New York, at that point in full “gentrification.” Armed with a Rolleiflex 6×6 film camera (at the very moment digital photography was about to triumph), she began to capture each window of an endangered local retailer, threatened by the expansion of large chain stores and malls. This inventory of milliners, hairdressers, hardware stores, cobblers and television repair places also documents the waves of immigration happening at the same time as media images were developing of New York as the capital of the twentieth century. Also fascinated by recycled textiles, the artist followed each step of the path of used clothing; sold, worn again, then sold again, in batches across the world. She went as far as Cuba, Asia, and Uganda to photograph various styles and the bundling of things in the global economy: more than 10,000 photos—including about 400 selected by her for a book and several exhibitions, organized into different chapters and maps—of what she modestly calls, “her everyday life.” Leonard has exhibited in many international institutions.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017