Julia Margaret Cameron

Schirmer Lothar, Bronfen Elisabeth,Women seeing women: a pictorial history of women’s photography in the 19th and 20th centuries from Julia Margaret Cameron to Ineez van Lamsweerde, Munich, Schirmer, 2020 (2th ed.)

→Fry Roger Eliot, Woolf Virginia and Cameron Julia Margaret, Julia Margaret Cameron, London, Pallas Athene, 2016

→Cox Julian and Ford Colin, Julia Margaret Cameron: the complete photographs, London, Thames&Hudson, 2003

Victorian Giants: the Birth of Art Photography: Julia Margaret Cameron, Lewis Carroll, Clementina Hawarden, Oscar Rejlander, National portrait gallery, London, March 1 – May 20, 2018; Millennium gallery, Sheffield, June 30 – September 23, 2018

→Julia Margaret Cameron: 19th century photographer of genius, the National Portrait Gallery, Lodon, February 6 – May 26, 2003; the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford, June 27 – September 14, 2003; and at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, October 21, 2003 – January 11, 2004

→Julia Margaret Cameron: 1815-1879, John Hansard Gallery, University of Southampton, February 8 – April 1, 1985

British photographer.

Julia Margaret Pattle was born in Calcutta to an East India Company agent and a French aristocrat. She mainly grew up in Versailles, alongside her maternal grandmother Thérèse de l’Étang, and returned to India at the age of nineteen, where in 1838 she married Charles Hay Cameron, an English jurist and social reformer. In 1848, on the latter’s retirement, the couple returned to England with their large family (they would eventually have six children of their own and adopt five more).

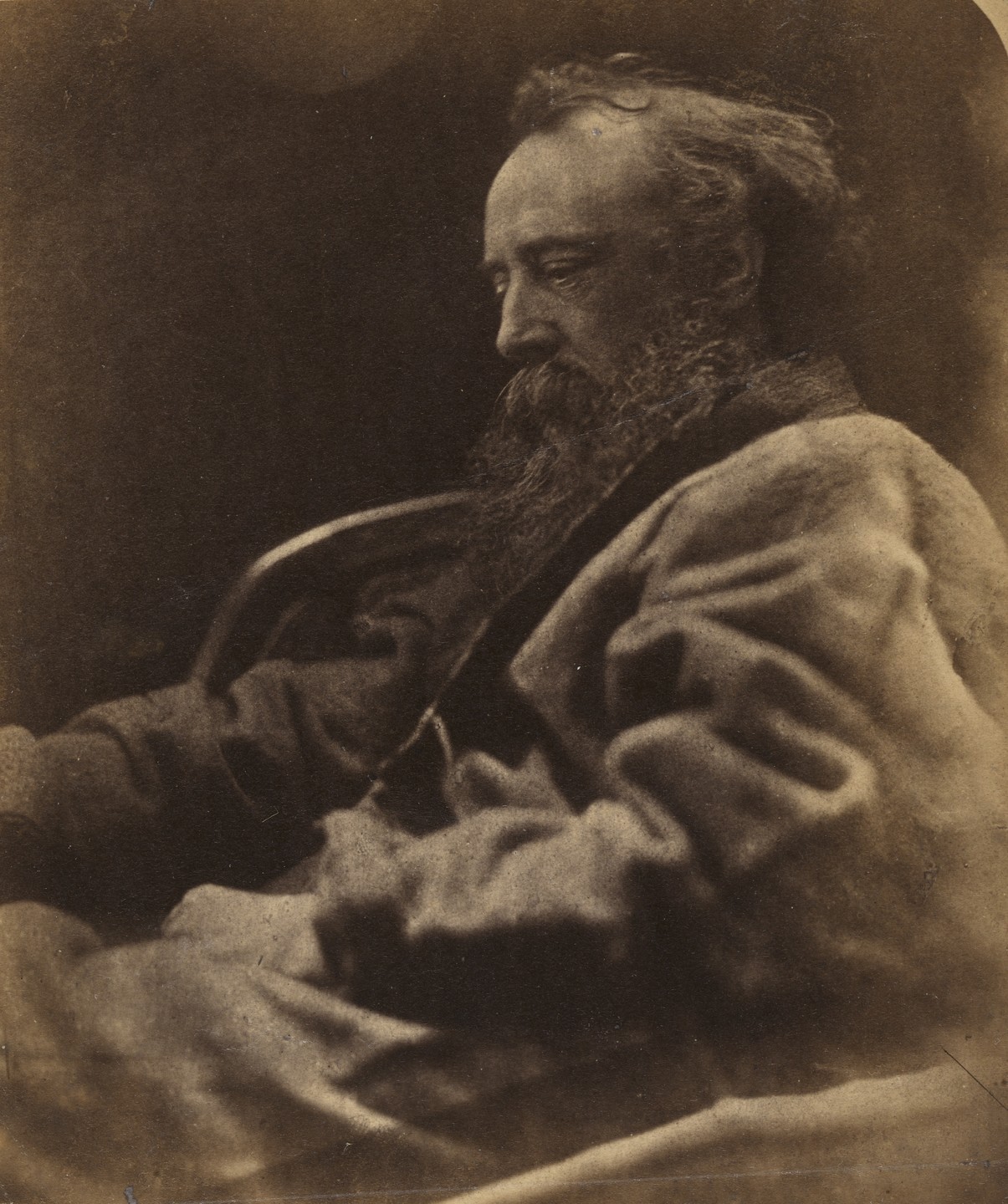

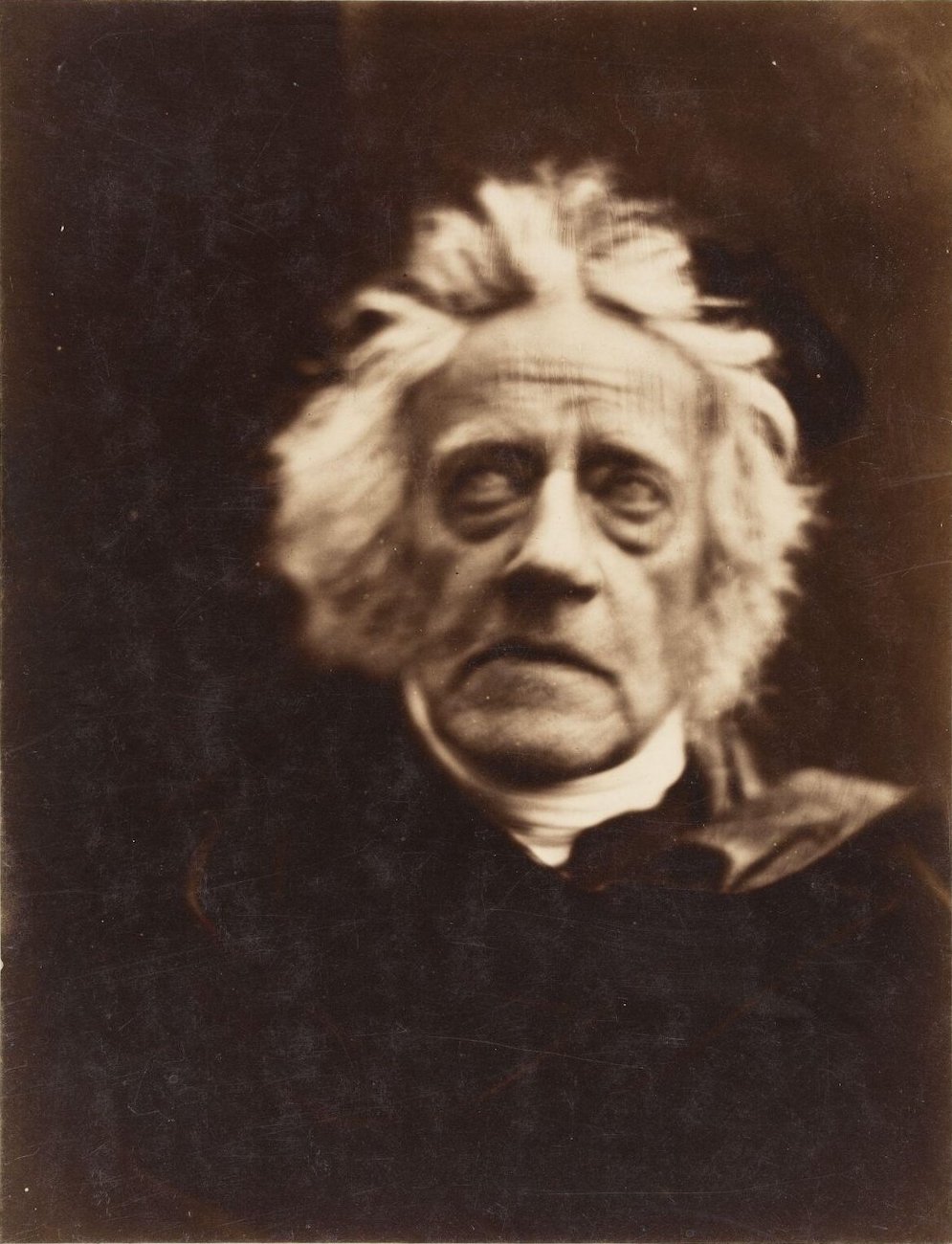

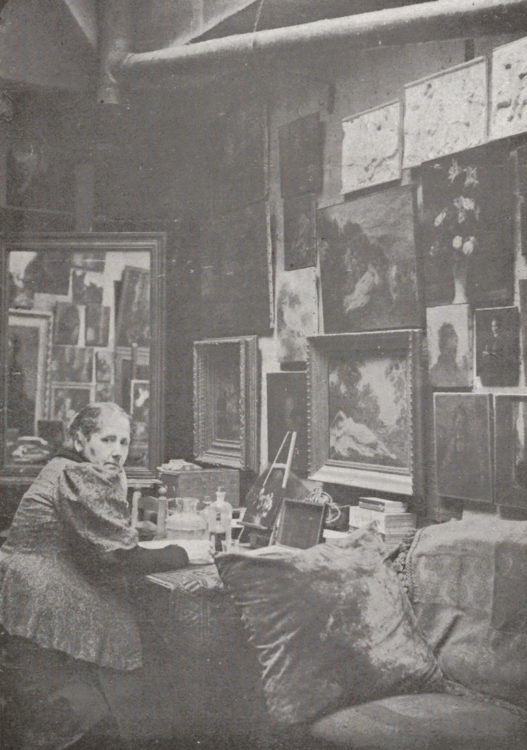

J. M. Cameron was forty-eight when she received her first box camera, a gift from her daughter and son-in-law. Highly cultivated, she rapidly developed lofty ambitions, aspiring “to ennoble Photography and to secure for it the character and uses of High Art by combining the real & Ideal & sacrificing nothing of the Truth by all possible devotion to Poetry and beauty”. This approach was partly an offshoot of long years of involvement with Little Holland House, the home of her sister Sara Prinsep, who in the 1850s had turned it into one of London’s signature literary and artistic hubs. The painter George Frederic Watts (1817-1904), who had set up his studio there, and poets Henry Taylor and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, two of its most assiduous followers, were all close friends of J. M. Cameron. Acquainted to many renowned members of the Victorian intelligentsia, she would indeed forge her own path as an artist firstly by displaying her talent for portraying these illustrious peers, who included scientists Sir John Herschel and Charles Darwin, and historian Thomas Carlyle.

Apart from Julia Jackson, the photographer’s niece and goddaughter – and the future mother of writer Virginia Woolf and painter Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) – few women on the other hand had the privilege of simply being themselves in front of the camera. J. M. Cameron’s female and child models, recruited from among family and friends, as well as staff and fellow Isle of Wight residents, lent their features to literary, mythological and religious characters in her figure studies and photographed tableaux vivants.

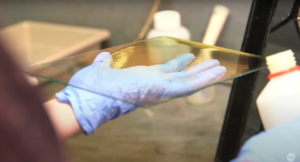

Perfectly aware of her own talent, J. M. Cameron advocated a quintessentially free approach to the photographic medium, conveyed by means of a highly personal and original aesthetic. The expressiveness of the blurred shots and the lighting, the daring close-ups, the open acknowledgment of streaks, scratches and other traces of the manual and experimental aspects of the creative process: by breaking with the photographic conventions of the time her immediately recognisable style earned her as much mockery as praise over the course of her short career, a decade punctuated by a true outburst of creative fever.

The latter rapidly faded away, in the wake of the Cameron couple’s move to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1875, motivated by a desire to get closer to their children and to the management of the family’s coffee plantations. At that stage the photographer’s works numbered some 1,200 images, multiplied through thousands of silver salt prints which proved particularly vulnerable to the ravages of time. Before leaving England she had selected seventy photographs intended to be reproduced as carbon prints, a process designed to inalterably preserve and disseminate what she considered to be the best of her work. By the turn of the century, J. M. Cameron was already recognised in the Anglo-Saxon world as one of the tutelary figures of photographic art. Today she ranks among the nineteenth-century photographers to have inspired the greatest number of solo exhibitions.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021

Julia Margaret Cameron | Victoria and Albert Museum

Julia Margaret Cameron | Victoria and Albert Museum  Julia Margaret Cameron’s working methods | Victoria and Albert Museum

Julia Margaret Cameron’s working methods | Victoria and Albert Museum