Research

Photo of female students at the Institut franco-chinois de Lyon. Funü zazhi [Ladies’ Journal], vol. 8, no. 7, July 1922, Shanghai

This article gives an overview of Chinese women’s contribution to the art reform and the changing gender roles in Chinese society of the early twentieth century. This period not only saw the fall of imperial rule and the establishment of the new republic in 1912, it also saw seismic shifts in the views of women’s roles in society. The article discusses how women artists, through their involvements in art education, national and international exhibitions, publishing, and art organizations, engaged in the dialogues of modernity and modernism in Chinese art and asserted women’s voice in the artistic milieu.

At the turn of the twentieth century the discourse of “woman question” (funü wenti) was one of the most pressing debates on national survival and strengthening in the late Qing and early Republican social-political thinking as China encountered foreign aggression and internal crises. Women’s education – what women should learn and to what ends – was at the crux of these debates. Bracketed by the reassessment of traditional culture and the influx of Western knowledge and thinking, women’s public display of talent – a notion that was traditionally discouraged – was to be redefined and repurposed. And women were to be participants in this repurposing in unprecedented ways. The New Policies promulgated in the last years of the Qing dynasty led to the sanctioning of public education for women for the first time in Chinese history in 1907. Mandates of the new education stipulated that on the one hand, the curricula should enrich women with knowledge in domestic duties, on the other hand, women should be equipped with skills for income-earning occupations. To this end, curricula of women’s schools foregrounded arts and crafts as both domestic and vocational skills, which included varied types of womanly handiwork (nügong), and painting and drawing. It also stressed that vocations in the arts and crafts were suitable for women as they aligned with female temperament.

In 1904, embroiderer Shen Shou (1874–1921) was appointed as the chief embroidery instructor for noble women in Empress Dowager Cixi’s (1835–1908) court and was charged with the renewal of the practice. While Shen continued to work with traditional subject matter, she adopted elements from new-style Japanese fine-arts embroidery, and Western painting and photography. Her work was a crossover between Chinese, Japanese and Western aesthetic idioms and was frequently displayed at various world’s fairs, such as her embroidery Portrait of Jesus, based on a Renaissance painting, shown at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. Shen’s stories demonstrate how women’s handicrafts, in particular embroidery, were championed in the expanding definition of Chinese cultural heritage during an era of global competition for cultural superiority.

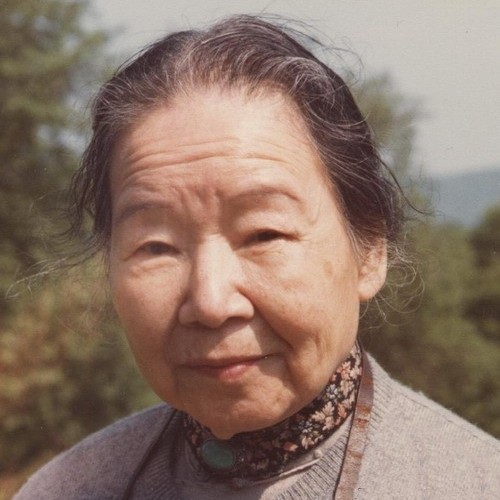

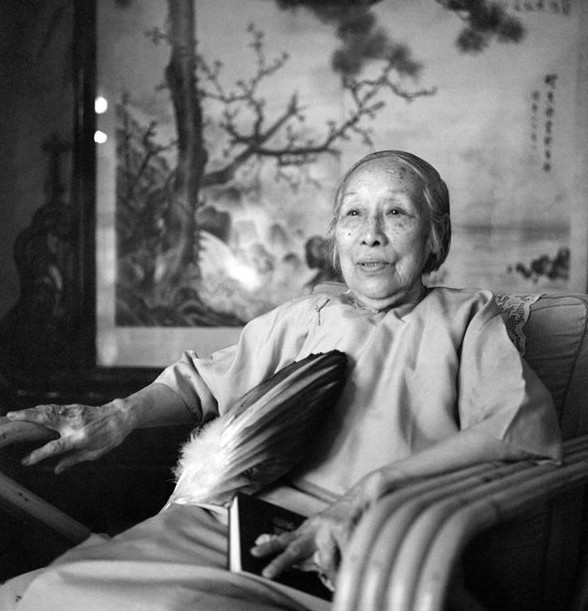

While women were encouraged to renew the practice of embroidery as a way to contribute to society, painting and calligraphy – the epitome of elite learning – was also an encouraged practice for women to engage in the public cultural arena. To emphasize its distinctiveness in global culture, traditionalist painting and calligraphy were promoted as important markers of modern expressions and women artists were to participate in unprecedented ways in this traditionally male-dominated milieu. Wu Xingfen (Wu Shujuan, 1853–1930) and Jin Taotao (Jin Zhang, 1884–1939) were representatives of the cohort of women artists who advanced the artistic legacy of their predecessors, while at the same time expanding the paradigm of traditional art practices. A well-respected female artist who did not speak a word of English, Wu’s works were auctioned at charity events catering primarily to Europeans and Americans clients, organized by groups such as the American Red Cross Society in Shanghai. She also published two bilingual albums of her works.1 Wu, who followed the tradition of the Qing Orthodox School, produced most of her works in the styles of past masters. Her relatively conservative approach to art, however, was precisely her way of embracing the renewal of the art form as modern expressions. While acting as the guardian of traditional-style art, Wu also actively engaged in publishing, commerce, mixed-gender and cross-cultural social events – opportunities that were unique to the experience of a modern artist.

Jin Taotao was born into a successful silk merchant family in the southern city-port Nanxun. She was one of the small number of women who had the opportunity to receive an elite public education in the early 1910s. She also had the opportunity to sojourn in London with her sister and brothers, and lived briefly in Paris, where her husband served as a diplomat at the Chinese embassy. Jin’s work revitalized the notion of zhen (truth or realism) in Song dynasty painting, which was promoted as archetype of Chinese visual culture.2 Like many artists of the time, Wu and Jin were members of the burgeoning art societies, and both played active educational and administrative roles in these organizations. Membership in art societies not only granted opportunities for artists to show their work in local venues; it also increased their chances of participating in international exhibitions. Both Wu and Jin showed their work in many such venues, including the 1911 International Exhibition of Art in Rome, and the 1930 Exposition Internationale in Liège, Belgium. Women artists’ participation in international events was central to cultural diplomacy as the works displayed signalled both cultural achievement and social progress. Wu and Jin were the first generation of women whose art and public visibility exemplified the repurposing of female talent as a new virtue.

“Calligraphy and Painting by Women,” Libailiu [Saturday] 556, June 2, 1934, Shanghai

“Calligraphy and Painting by Women,” Libailiu [Saturday] 556, June 2, 1934, Shanghai

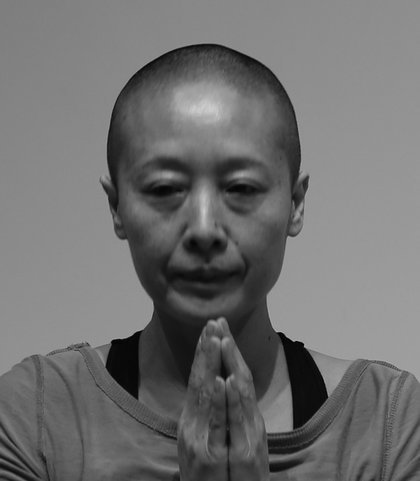

The Chinese Women’s Society of Calligraphy and Painting (1934–c.1948; hereafter cited as the Women’s Society) was established by and for women artists primarily engaged in the practice of Chinese-style painting. It was the only all-women organization among the numerous art societies of the early Republican period. It was founded by a group of well-established female artists in the traditionalist painting circle who believed that the founding of such an organization represented a pivotal step in the affirmation of women artists’ competence and contributions to the art world, as well as to society at large. With over two hundred members, the Women’s Society was a very large cultural organization by the standards of the time. Functioning as an agent and channel for the dissemination of the work of its members, the Women’s Society also facilitated the emergence of public roles for women – an increasingly important aspect of women’s life in the Republican society. This group of women also aspired to take their profession beyond the cultural-artistic realm and make their practices relevant to the needs of society. Based on the group’s activities, the establishment of the Women’s Society was driven in part by a patriotic concern for national survival. The society’s multifaceted social and cultural activities included charity sales and disaster- and war-relief efforts during a time when China faced imminent war with Japan. At a time of national peril, women artists further underlined the emergence of women as valuable citizens. While their works still anchored in the traditional visual idioms, members of the Women’s Society had surpassed their predecessors in publicness by making their presence prominent in print media and other public channels. They were adept at using the media to advertise their exhibitions to ensure exposure and assert women’s agency in the art world).

Photo of female students at the Institut franco-chinois de Lyon. Funü zazhi [Ladies’ Journal], vol. 8, no. 7, July 1922, Shanghai

While traditionalist art was revived as important modern expressions, Western-style art was developing simultaneously in the Chinese art world. Pan Yuliang (Pan Yu-lin, 1895–1977), Fang Junbi (Fan Tchun-pi, 1898–1986), Wang Jingyuan (1893–?), and Guan Zilan (Violet Kwan, 1903–1986) were among the female artists who practised Western-style art. They received art training in the burgeoning specialized art schools in Shanghai and benefited from an education abroad after the Republican government began to implement overseas study programmes in the early 1920s.

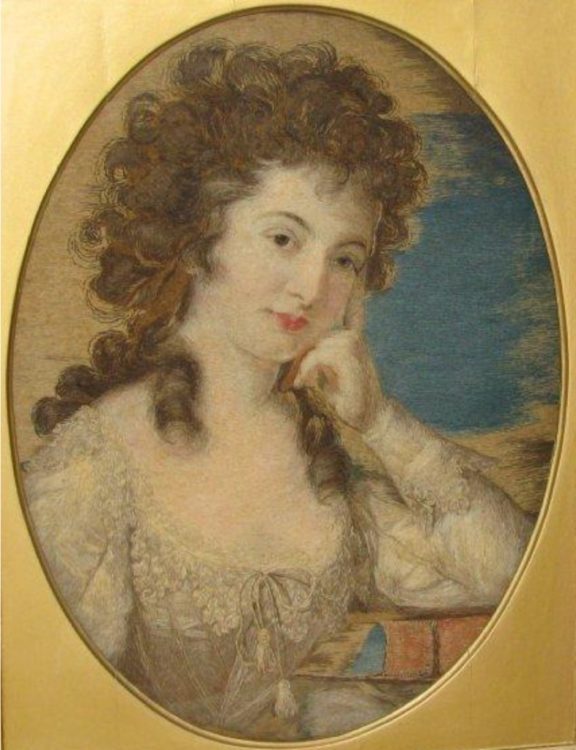

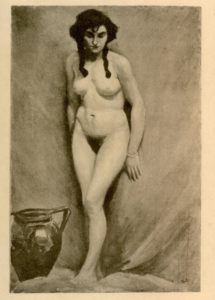

Pan Yuliang, A Young French Woman, 192, in Oil paintings by Pan Yulaing, Shanghai, Zhonghua shuju, 1934, plate #1

Pan Yuliang, A Young French Woman, 192, in Oil paintings by Pan Yulaing, Shanghai, Zhonghua shuju, 1934, plate #1

Pan and Wang both studied at Institut Franco-Chinois de Lyon. Pan later attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome, and Wang enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux.3 Pan and Wang dealt with the nude, which was an unusual subject matter in Chinese visual culture.4 Wang was also one of the few artists during this period whose main medium was sculpture. Fang Junbi went to France with her sister at the age 14. In 1920 she became the first Chinese female student to enter the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.5 Guan was among the Chinese artists who pursued their art education in Japan. She graduated from Bunka Gakuin, an academy for culture in Tokyo and was known for her Fauvist-style painting.6 After returning to China in the late 1920s, these women artists, together with their male colleagues, actively engaged in the production of Western-style art. Overseas education enabled them to gain cultural capital and advance their career prospects in both the Chinese and global art worlds. They dared to depict new subject matter, devise new artistic styles, and confidently assert their position as pioneers in the development of Western-style art in China.

Artists mentioned in this article were not only important to advancing women’s status in the art profession, they also made tremendous contributions to the lively and yet controversial debates over the direction of Chinese modern art in the early twentieth century. They strived to pursue artistic languages that would represent their voice, even though that voice was often overshadowed by the nationalistic rhetoric of China’s new art. Their presence and engagement as artists, educators and public intellectuals nonetheless gave them agency in asserting gender consciousness in their work and life.

Wu Xingfen, Zhongguo jinshi nüjie dahuajia Wu Xingfen hua (Chinese Paintings by Madame Wu Hsing-fên, the Most Distinguished Paintress of Modern China) (Shanghai, 1915); Wu Xingfen, Zhongguo mingsheng tushuo (Eighteen Famous Chinese Landscapes Painted by Madame Wu Hsing- Fên, the Most Distinguished Paintress of Modern China) (2nd ed. Shanghai, 1926).

2

Wang Cheng-hua, “Rediscovering Song Painting for the Nation: Artistic Discursive Practices in Early Twentieth-Century China”, Artibus Asiae 71, no. 2 (December 2011): p. 229.

3

For the biography of Pan Yuliang, see https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/pan-yuliang/.

4

See Julia Hartmann, “Nudes in 1920s China: Emancipation and Agency in the Works of Female Artists,” https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/le-nu-dans-la-chine-des-annees-1920-emancipation-et-autodetermination-dans-les-oeuvres-dartistes-femmes/.

5

For the biography of Fang Junbi, voir https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/fang-junbi-fan-tchun-pi/

6

On Guan Zilan, see Amanda S. Wangwright, The Golden Key: Modern Women Artists and Gender Negotiations in Republican China (1911-1949) (Leiden: Brill, 2020), pp. 15-33.

Doris Sung is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Alabama. Her research focuses on early modern, modern and contemporary art of East Asia, cultural interactions between Asia and Europe, and gender and visual culture. She has published several book chapters and articles on Chinese women artists active in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. She has contributed entries on modern and contemporary Chinese art for Grove Art Online. She is currently working on a book on the contribution of women artists to Chinese art reform and gender positioning.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.