Research

The second half of the 19th century, with the regimes of the Second Empire (1852-1870) and the Third Republic (1870-1940), marked a gradual stabilisation of France following the upheaval of the Revolution and the political instability that ensued. It was also during this time that the idea of a modern French national identity was consolidated. The large-scale urban renewal of Paris led by Georges Eugène Haussmann, and a number of major construction projects such as the Opéra Garnier, Hôtel de Ville and the ambitious project for the Nouveau Louvre involved a thorough transformation of the capital, which went hand in hand with the deep cultural transformations the nation was undergoing at the time.

At first motivated by the celebration of the sovereignty and values of the state, statuary took on a more didactic and nationalistic role under the two regimes: after 1870 sculptures became prevalent as ways to disseminate the new republican ideals. The extent of this phenomenon, which pervaded not only Paris but also the rest of the country and the rest of Europe, earned it the name of “statumania”1: every public, semi-public and private space was suddenly flooded with busts and portraits2 glorifying heroes of the nation, great literary and scientific minds, major political personalities and a number of female allegorical figures, nude or semi-nude, inspired by Antiquity. The women in these works were objectified in typical 19th-century fashion, that of a patriarchal bourgeoisie in which the – male – public could, both for aesthetic and erotic purposes, gaze upon female bodies anonymised by means of the allegory.

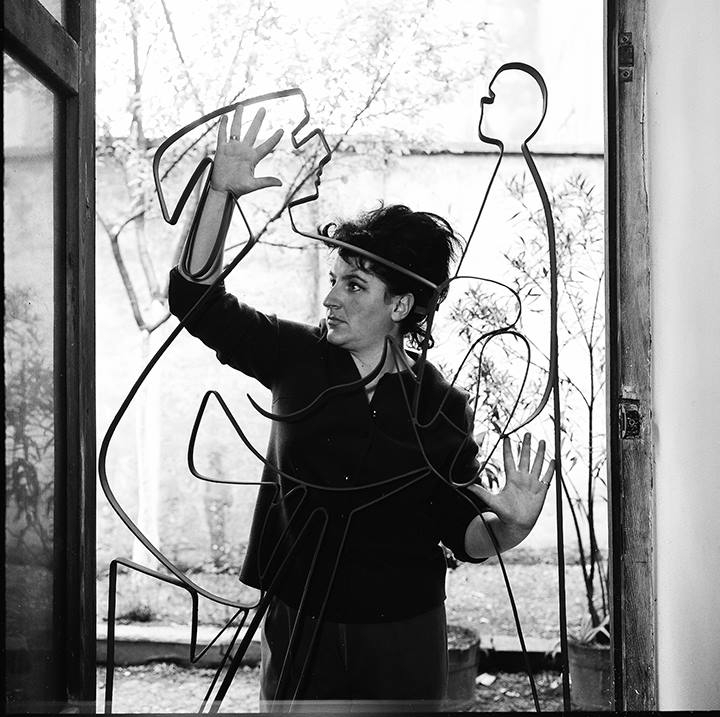

Marie-Louise Lefèvre-Deumier, Nymphe Glycéra or La Couronne de fleurs, 1861, Palais du Louvre, cour carrée

In such a context, where women were made to be systematic subjects of representation rather than producers of an artistic gaze, it is hard to imagine any woman artist asserting herself as a sculptor. Furthermore, the Beaux-Arts de Paris, which at the time provided the only official training in painting and sculpting, was not open to women before 1897, thus keeping them outside academic circles throughout the 19th century and limiting their opportunities to train, particularly in the field of sculpture. A few private academies, such as the Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi, gradually started to take them in, but most women learnt their trade from their male relatives, fathers, brothers or husbands, or at artist studios. This was the case for Hélène Bertaux (1825-1909), who studied with her stepfather Pierre Hébert (1804-1869), and of Claude Vignon (1832-1888), born Marie-Noémi Cadiot, who studied in the studio of James Pradier (1790-1852). These two artists were among the few women to win prizes for their sculpture at the Salon, in addition to Félicie de Fauveau (1801-1886) and Marie-Louise Lefèvre-Deumier (1812-1877). Sculpture was a gendered art: the physical requirements of the practice were associated with manly qualities, therefore excluding women from the profession. In the case of public statuary specifically, the idea of a woman creating monumental works for the urban space was hardly acceptable to the public – and patrons – in those days. And so, as statumania took over Paris, it was almost exclusively left to men. With the exception of indoor public spaces, such as the Louvre and the staircases of the Palais Garnier, and of semi-private spaces like graveyards, only three women artists were entrusted with state-commissioned works in Paris: H. Bertaux, C. Vignon and M.-L. Lefèvre-Deumier.3

Among other undertakings, these three artists took part in the Nouveau Louvre project (1851-1936), the goal of which was to connect the Louvre Palace to the Tuileries. This project prompted a vast number of commissions for an ambitious sculpted decor depicting the illustrious male figures who embodied the scientific, literary and philosophical advances of the time, as well as the development of trade and industry, celebrating French prosperity and intellectual achievements. Such were the many symbols of national glory that were added to the facades, among which La Navigation (1864) and La Législation (1878) by H. Bertaux, flanked by the figures of Moses and Charlemagne (1878).

The values that these works displayed – the history of France as a conquering, modern, culturally influential and economically strong country – and the sparse number of women hired to create them highlight an obvious disinterest in including women citizens in the ambitious project of a roman national (national myth).4 The case of Paris’s city hall is particularly telling. The building’s facade was renovated from 1874 to 1882 after it sustained damage during the Commune (1870-1871), which came as an opportunity to create a grand outdoor gallery of illustrious Parisians. Only six of these statues were of women,5 and only H. Bertaux again was invited to participate with a portrait of Jean Siméon Chardin (1699-1779). Furthermore, the selection process of the artists for these urban decorative projects shows that these three women were not specifically chosen for their gender, meaning that there was no conscious effort on the part of the state to showcase women artists. Rather, these opportunities were more likely the result of networking and reputation. For instance, C. Vignon, who was at first supportive of the Empire and critical of the Republic,6 ceased to receive commissions after the change in regime and was not included in the Hôtel de Ville project. M.-L. Lefèvre-Deumier, who had close ties with the empress, no longer had her works shown at the Salon after 1873, under the Republic.

Vignon (Marie-Noémi Cadiot-Constant Rouvier, know as), Rinceaux habités d’enfants, 1862, stone, Saint-Michel fountain, Paris

Cultivating a substantial artistic and political network was therefore imperative, albeit not the only condition, if one was to receive commissions. C. Vignon’s order for several sculptures for the Nouveau Louvre exemplifies the way in which an artist’s career could develop both through their skills and relationships. In all likelihood, C. Vignon’s privileged relationship with the architect Hector Lefuel, who was her lover, prompted him to recommend her for the creation of additional sculptures when one of the artists previously hired for the project dropped out. However, his choice can also be attributed to the existence of a group of successful sculptures C. Vignon had made for the Ministry of Fine Arts, as well as to her good work ethic.

The study of H. Bertaux’s correspondence with the Ministry of Fine Arts shows not only the degree to which she was in control of her own career, but also her ability to make bold moves. Her Psyché sous l’empire du mystère [Psyche under the empire of mystery, 1889],7 now visible in an alcove outside of the Palais du Luxembourg, was first acquired by the state for 7,000 francs, after which the artist renegotiated the price up to 10,000 francs by arguing that it was a more typical fee for this kind of work. She also arranged for the piece to be shown at the Musée du Luxembourg in place of another of her sculptures, which she had moved to the Palais de l’Élysée by way of a letter of appeal she wrote to President Sadi Carnot’s wife, Cécile Carnot, whom she barely knew.8 This determination on H. Bertaux’s part went hand in hand with her commitment to feminism,9 which she expressed through her campaigning for the admission of women to the school of fine arts, the creation of the union of women painters and sculptors, and her salon, which enabled her female peers to exhibit and sell their works. Her fight is manifested in her letters to the board of the École des Beaux Arts, in which she pleaded the cause of her peers, praising their “courage and selflessness for the triumph of women’s art”,10 and never failing to bring up the difficulties that women faced in the profession. In May 1889 she wrote: “I will consider the work I have shown at the Musée du Luxembourg a great honour and a signal to other women … of what they can expect from your tutelary fairness as the director of the École de Beaux Arts when their efforts as artists are at long last acknowledged.”11

Hélène Bertaux, Psyché sous l’empire du mystère, before 1897, © Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Unfortunately, her pleas did not have any visible effect on the board of directors’ decisions. While H. Bertaux’s activism is indeed commendable, the fact remains that her personal success came partly as a result of the bourgeois network she managed to build for herself. Her talent, while undeniable, cannot be considered the only reason for her exceptional career. The three sculptresses we have mentioned are all exceptions, and their sculptures were never the most imposing or most central pieces in the projects they took part in. C. Vignon made her contribution to the Saint-Michel fountain, which was inaugurated in 1860, but only to create its scrollwork and plant motifs. All these examples are but lacklustre victories for the inclusion of women in national artistic creation and merely evidence the individual successes of both worthy and privileged figures rather than a genuine will to include women and promote their participation in the art world of their time. Likewise, religious institutions, which were also taken over by statumania, only commissioned a few sculptresses to renovate facades, such as the Saint-Laurent church, for which H. Bertaux created two sculptures of saints (1868).

In the first quarter of the 20th century the craze for public statuary, while it did not disappear completely, became less widespread and began to mutate. Other spaces such as cemeteries, semi-private locations commonly frequented by Parisians, became open-air museums that allowed many women to practice their art more freely.12 These spaces, which were not dependent on public commissions, but rather on social and private networks, were in this sense more open to these artists than large-scale state-sponsored projects. So in the early 20th century, artists such as Laure Coutan (1855-1915), Marguerite Syamour (1857-1945) and Jeanne Itasse (1865-1941) figured among the contributors to funereal art. This type of art presented itself as an alternative to official art, which persisted, time and again, in the celebration of men, whose portraits were sculpted by other men who, in turn, would also be immortalised in marble.

For further details on this subject, see the works of Maurice Agulhon in his article “La ‘statuomanie’ et l’histoire”, Ethnologie française 2-3 (1978): pp. 145-172.

2

For a more detailed explanation of the statuary craze in Paris, see Hargrove June, “Les statues de Paris”, in Les Lieux de mémoire, t. II, La Nation: la gloire, les mots, vol. 3, ed. Nora Pierre (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), pp. 243-282.

3

For a more detailed study of the presence of women in the urban space in Paris, London and Brussels, see the works of Marjan Sterckx, who addressed the subject comprehensively and whose insights were invaluable in putting together this research.

4

The term “roman national”, which has been used to describe the construction of a national history and culture since the late 19th century, was popularised in France by the historian Pierre Nora. This construct is nowadays contested and questioned, especially because it relies on an idealised conception of the nation and its history, which tends to exclude minorities and minimise certain problematic aspects of history.

5

With the exception of the painter Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), the six women depicted on the facade are all women of letters or salon hostesses.

6

On the subject of C. Vignon’s political views, see among other works Guentner Wendelin, “Claude Vignon’s Salon de 1850-1851: Dialogues of Art and Ideology”, in Women Art Critics in Nineteenth Century France: Vanishing Acts, ed. Guentner Wendelin (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2013), pp. 141-172.

7

For a more comprehensive study of the work, see Sophie Jacques, La Statuaire Hélène Bertaux (1825-1909) et la tradition académique. Analyse de trois nus, Masters dissertation supervised by François Lucbert, Université de Laval, 2015, 173 p.

8

The full correspondence is kept in the national archives, entry F21 2055 A, in a file named Psyché sous l’Empire du Mystère. Parts of these letters are reproduced in the supplementary research dossier.

9

The notion of feminism must in this case be put back into a 19th-century perspective: although H. Bertaux campaigned for the emancipation of women and their right to exhibit their works, be paid accordingly and acknowledged on a professional level, she also held essentialist beliefs on the differences between men and women.

10

Letter from H. Bertaux to the director of the School, 4 May 1889, National Archives, F21 2055 A, Psyché sous l’Empire du Mystère file.

11

Ibid.

12

On the specific subject of funereal statuary, see Rivière Anne, “Un substitute de l’art monumental pour les sculptrices : la sculpture funéraire (1814-1914)”, La Sculpture au XIXe siècle. Mélanges pour Anne Pingeot, eds Chevillot Catherine and Margerie Laure de Paris: N. Chaudun, 2008, pp. 422-429.

13

Sur le cas particulier de la statuaire funéraire, voir Rivière Anne, « Un substitut de l’art monumental pour les sculptrices : la sculpture funéraire (1814-1914) », dans Chevillot Catherine et Margerie Laure de (dir.), La Sculpture au XIXe siècle. Mélanges pour Anne Pingeot, Paris, N. Chaudun, p. 422-429.

Cassandra Levasseur, "Women sculptors, public statuary and nationalism." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/sculptrices-statuaire-publique-et-nationalisme/. Accessed 13 March 2026