Lillian Schwartz

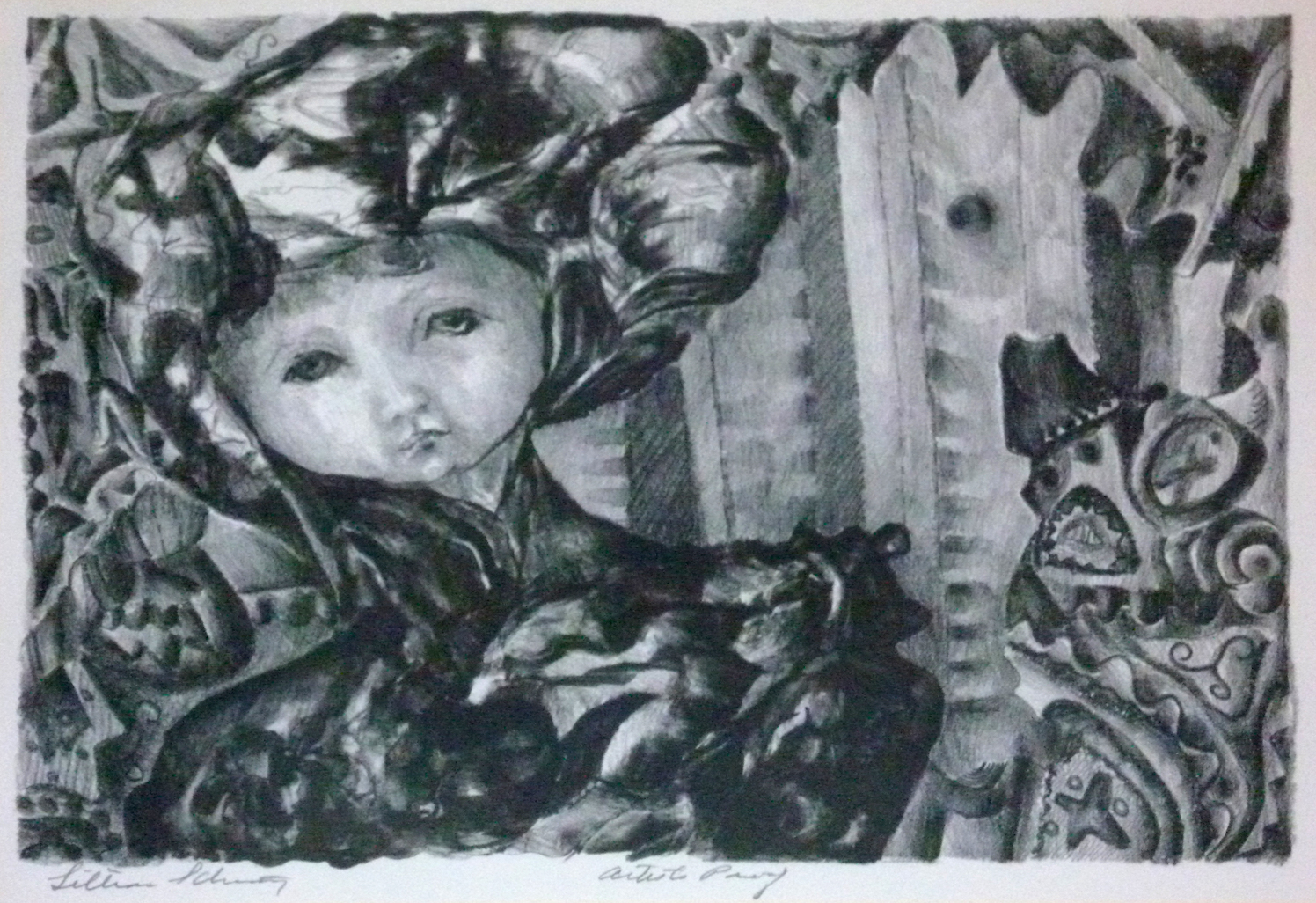

Manetti Renzo, Schwartz Lillian, Vezzosi Alessandro, Monna Lisa: il volto nascosto di Leonardo (Leonardo’s hidden face), Florence, Polistampa, 2007

→Kalantari Bahman, “Polynomiography: From the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra to Art”, illustrated by Lillian Schwartz’s color figure Brain, in LEONARDO, vol. 38, n° 3, June 2005

An Evening with Lillian Schwartz, Modern Mondays, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 10 décembre 2012

→GOOGLEPLEX, British Film Institute South Bank, 2005

→Algorithmic Revolution, Films at Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM), 2004

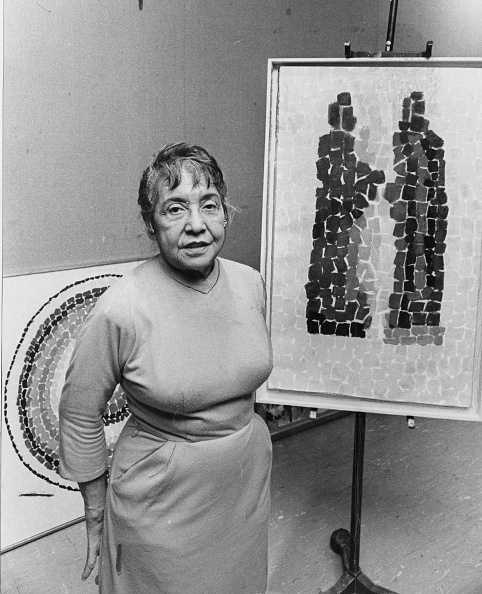

American videographer.

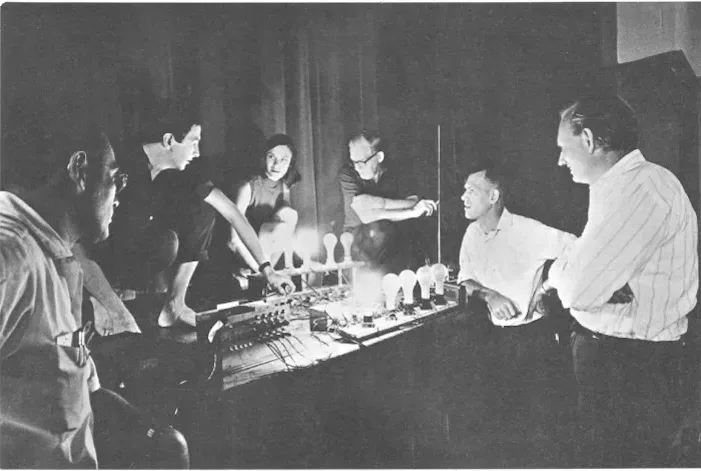

Lillian F. Schwartz is a pioneer of computer-generated art. In the 1970s, she made a series of abstract films exploring the formal potentialities of a technology whose language, still experimental at the time, offered unprecedented perspectives on the emergence of a new visual paradigm. Born into a large and modest family, L. Schwartz worked as a nurse in postwar Japan before studying drawing and painting, and then turning to kinetic art in the 1960s. She became an active member of the New York art scene, where she got to know the E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) group and took part in the exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age at the Museum of Modern Art in 1968. That same year, she became the first ‘unofficial’ female artist to be integrated within the team of scientists working at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey.

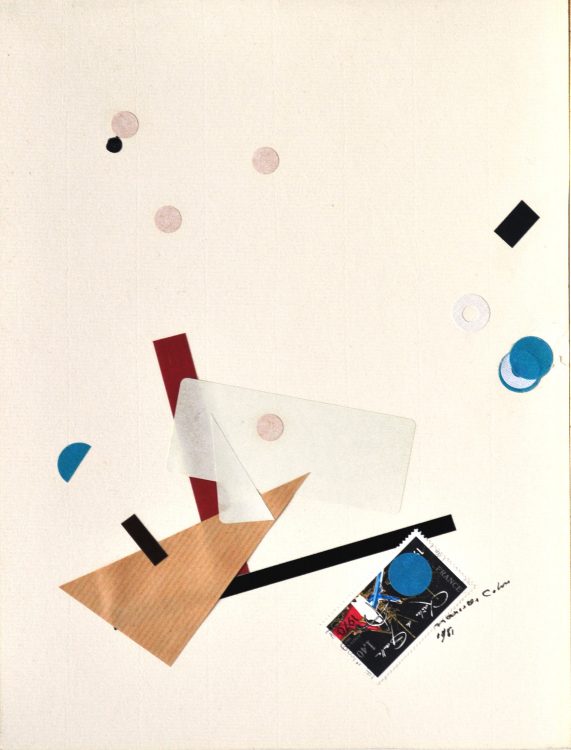

Working closely with the programmers Kenneth Knowlton(1931-), a pioneer of computer graphics and Max Mathews (father of digital music), L. Schwartz explored the limits of this new medium and broadened its applications to include the properties of the moving image. Her 16-mm films, based on the graphic palette offered by this technological environment, were hybrid experiments at the crossroads of the new digital technologies and the traditional techniques of analogue animated film. Generated by computer, the abstract motifs were reframed, subjected to various effects, and multiplied through the optical contact printer, before being assembled on the editing table.

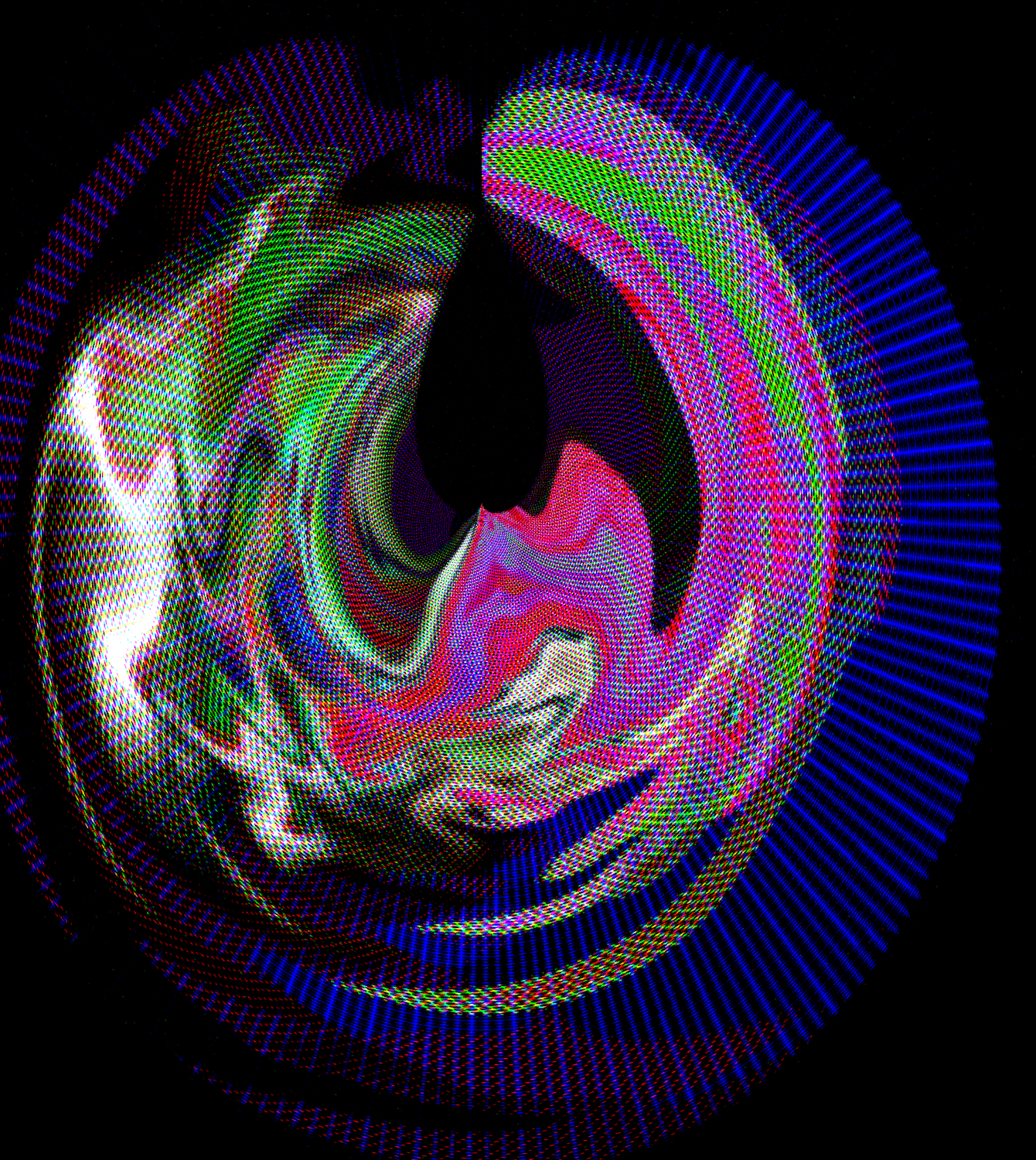

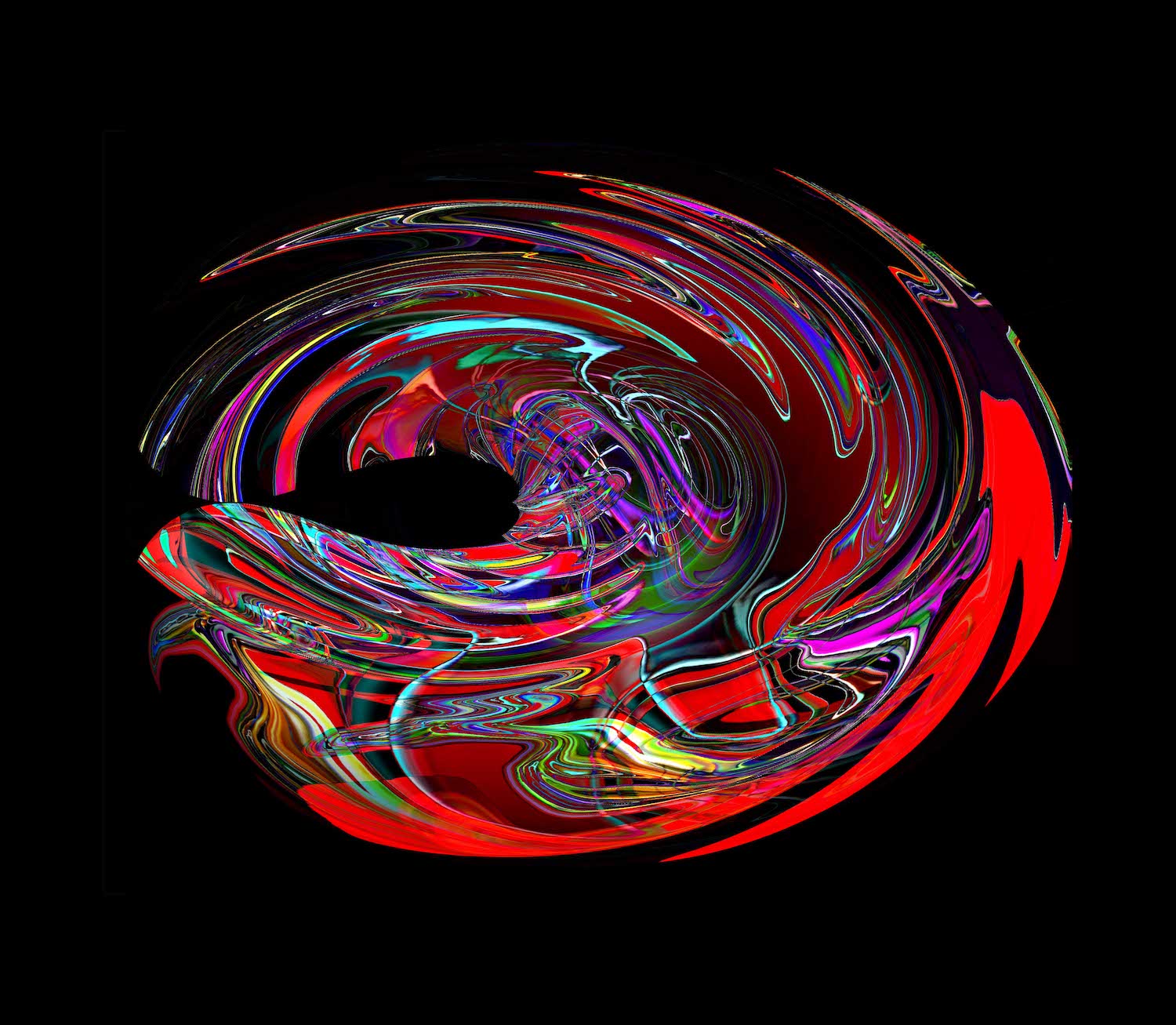

Her film Enigma (1972), produced after her early experimentations (Pixillation, 1970; UFOs, 1971) and noticed in both scientific and artistic circles, is an almost hallucinatory visual experience. Although abstract motifs based on elementary geometric shapes (such as lines and rectangles) appear on the surface of the frame, this modernist-inspired composition – reminiscent of some of Piet Mondrian’s (1872-1964) works – is gradually subjected to the stroboscopic effects of the flickering image, combined with the chromatic variations and an electronic experimental soundtrack by Richard Moore. L. Schwartz sees the computer as part of the natural evolution of the artist’s tools. She uses her films to sketch out a new, abstract iconographic vocabulary – what she calls ‘technological pointillism’1 – in order to question the physiological and psychological mechanisms of perception at a time of changing technological paradigms.

As published in Women in Abstraction © 2021 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London