Focus

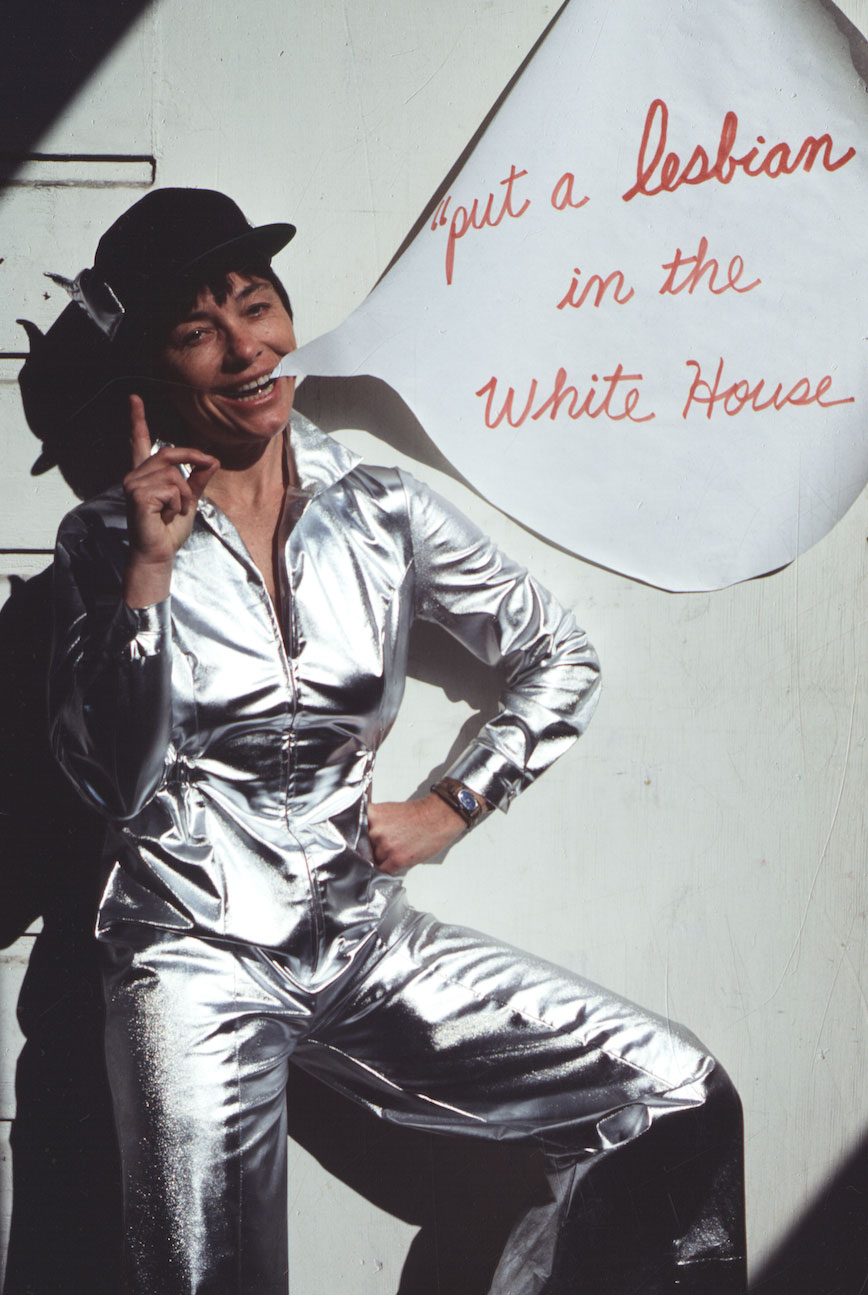

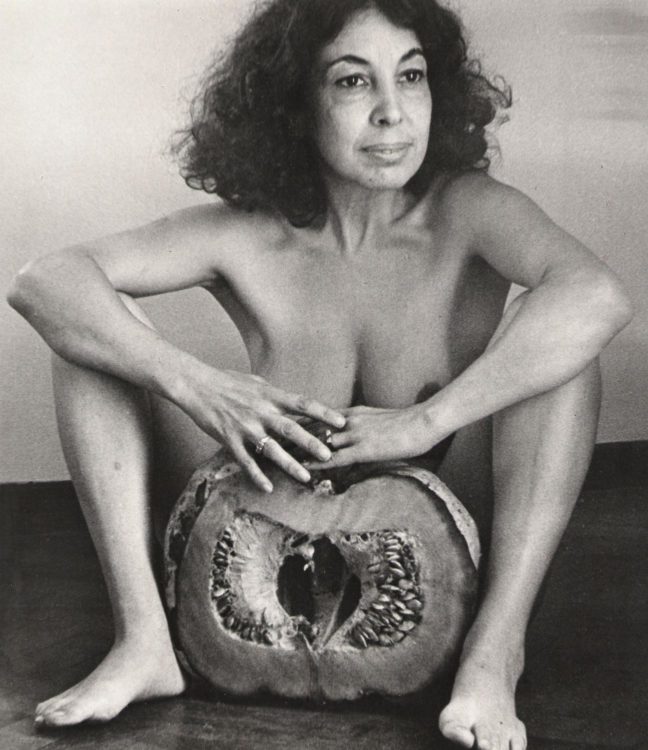

Barbara Hammer, Put a Lesbian in The White House, 1980, postcards & performance, Oakland, California © Estate of Barbara Hammer 2022

Though homosexuality has always existed, sexual orientation and gender identity are conceived differently according to place and time. In 19th century Europe, homosexuality, the term introduced in 1869 by Karl-Maria Kertbeny, was perceived “less as a sin of habit than as a singular nature”, in the words of Michel Foucault (1976). In parallel to this, the terms ‘sapphic’ and then ‘lesbian’ were gaining momentum, as female homosexuality raised wider questions about women’s place in society. Exploring social and identity positioning allows us to better understand how the history of homosexuality is tied to the history of representations. For how do we identify and express ourselves outside of the norms of gender and sexuality?

The question began to arise amongst artists towards the second half of the 19th century. At first they experimented for themselves, using photography privately rethinking representations of gender and the heterosexual couple. We see this in the rediscovered photographs of the American Alice Austen (1866–1952), the work of Norwegians Bolette Berg (1872–1944) and Marie Høeg (1866–1949), and then with the French Claude Cahun (1894–1954) and Marcel Moore (1892–1972), whose many self-portraits dig deeper into gender ambivalence.

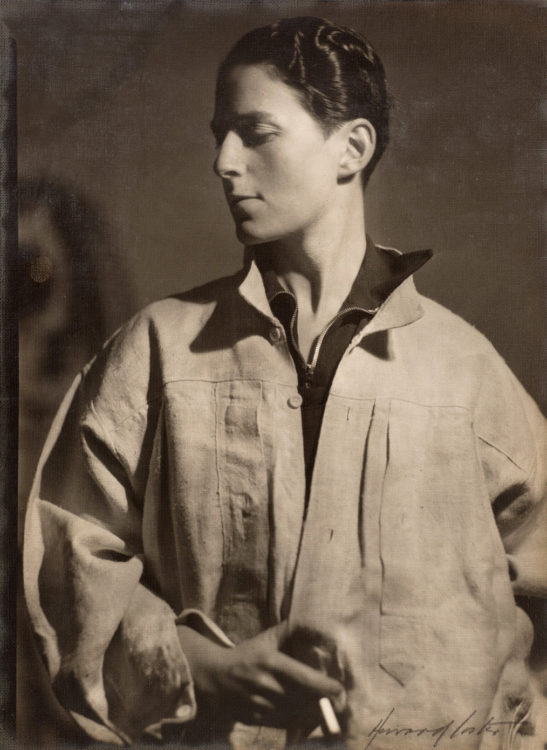

Meanwhile, a lesbian visual culture was emerging with its own attributes, which can be seen in numerous works. Notably, the painter Romaine Brooks (1874–1970) developed a new style of women’s portraiture, picturing her subjects in assertive and dynamic poses, in the outside world, in sober, modern dress – black jackets, high collars, neckties, monocles, tied-up hair – in images that evoke the early 20th century lesbian scene and its new recognition.

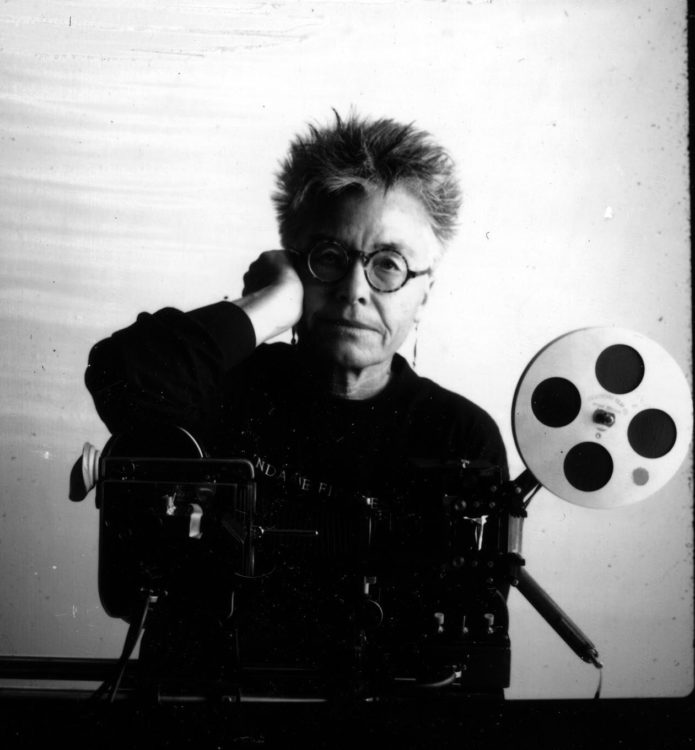

In the second half of the 20th century, beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, movements fighting for social rights would emphasise identity affirmation, and the conceptualisation of the word ‘lesbian’ would become part of a new, materialist political vision as found in the work of Monique Wittig. This was a turning point in the visual art world: sexuality and the lesbian community became fully fledged subjects of creation and emancipation. We see this in the experimental lesbian films of Barbara Hammer (1939–2019) and the photographs of Joan E. Biren (1944–) and Laura Aguilar (1959–2018), as well as in the work of the collective project Kiss & Tell. Created in the late 1980s in Vancouver, the collective’s exhibition Drawing the Line would question and defend lesbian sexualities.

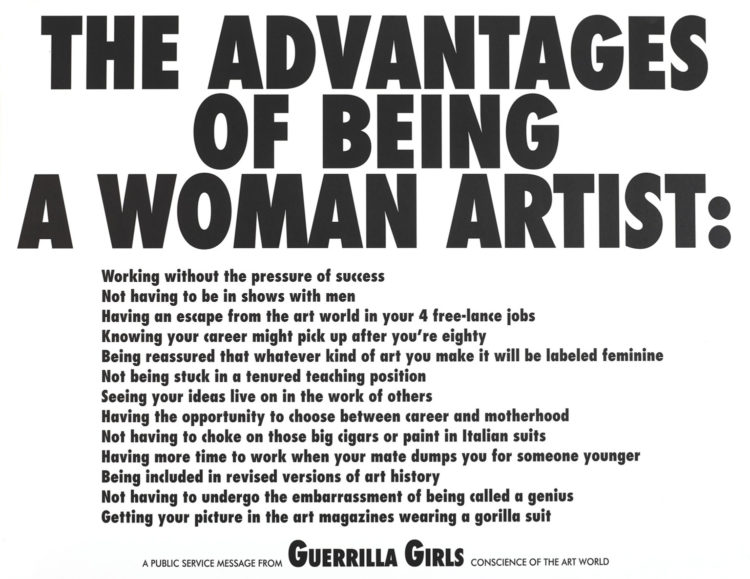

From the 1970’s, artists and historians raised the possibility of a lesbian history of art. The Based in Los Angeles, the Lesbian Art Project (1977-1979) was a participative research project exploring the history and meaning of lesbian art. Harmony Hammond’s (1944–) book Lesbian Art in America (2000) would also provide certain keys. However, writing an exhaustive history seems rather complex given the diversity of this lesbian and lesbo-queer visual culture in perpetual evolution.

1894 — France | 1954 — Jersey

Claude Cahun

1874 — Italy | 1970 — France

Romaine Brooks

1939 — 2019 | United States

Barbara Hammer

1959 — 2018 | United States

Laura Aguilar

1944 | United States

Harmony Hammond

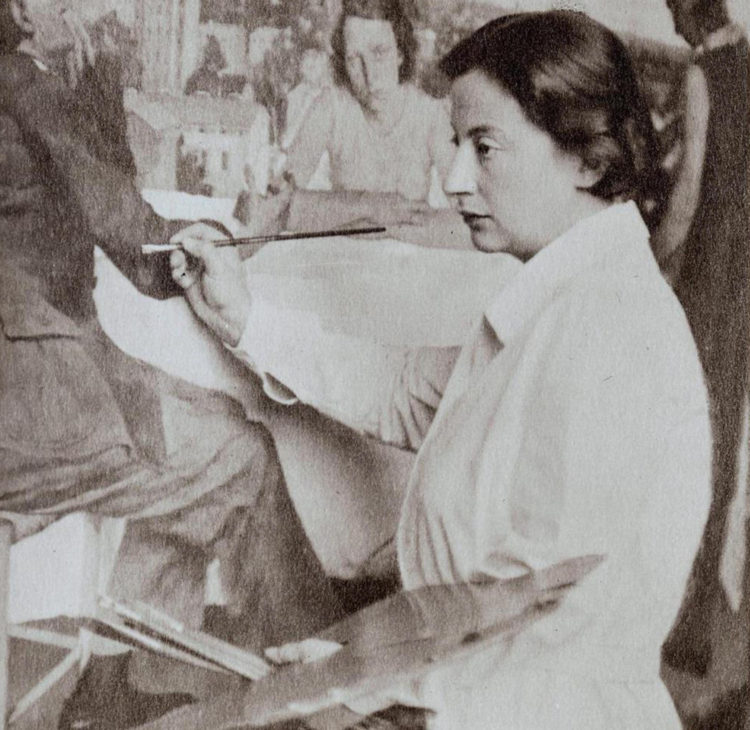

1883 — 1956 | France

Marie Laurencin

1898 — Poland | 1980 — Mexico

Tamara de Lempicka

1885 — 1940 | Denmark

Gerda Wegener

1895 — 1978 | United Kingdom

Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein, dite)

1898 — Prussia (now Pasłęk, Poland) | 1993 — Sweden

Lotte Laserstein

1951 | United States

Donna Gottschalk

1965 | France

Nicole Eisenman

1961 | United States

Catherine Opie

1972 | South Africa

Zanele Muholi

1971 | United States

Mickalene Thomas

1972 | Israel

Rona Yefman

1992 | Spain

Cabello/Carceller

1954 | Vietnam

Hanh Thi Pham

1951 — 2021 | Japan

Tāri Itō

1929 | Argentina

Ilse Fuskova (Felka)

1900 — Ukraine | 1992 — Israel