Review

Christina Broom, Jeunes suffragettes faisant la promotion de l’exposition de la Women’s Exhibition de Knightsbridge, 1909, photomecanical print, © Christina Broom/Museum of London

That’s the question posed by two exhibits reevaluating the important contribution of women to this artistic practice, one at the musée de l’Orangerie (1839-1919), and the other at the musée d’Orsay (1918-1945).

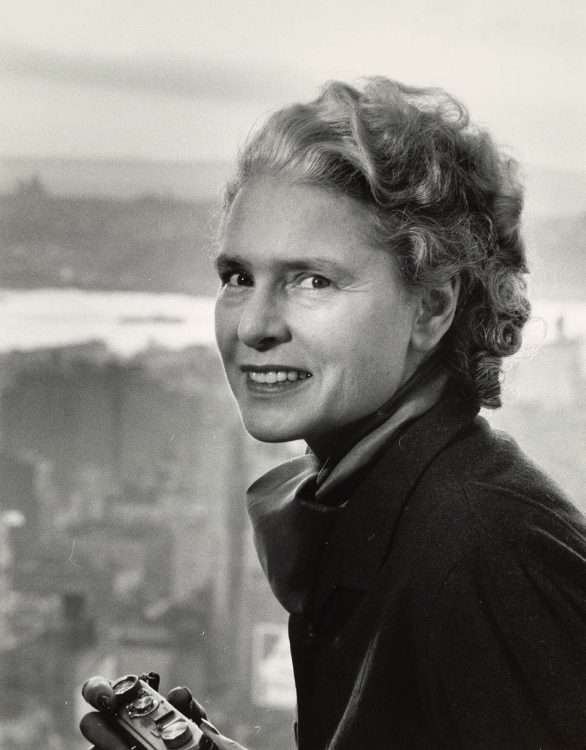

Ruth Bernhard, Doll, 1938, print in 1974, sliver print, 17,78 x 18,42 cm, © Trustees Princeton University © Digital Image Museum Associates/LACMA/Art Resource NY/Scala, Florence

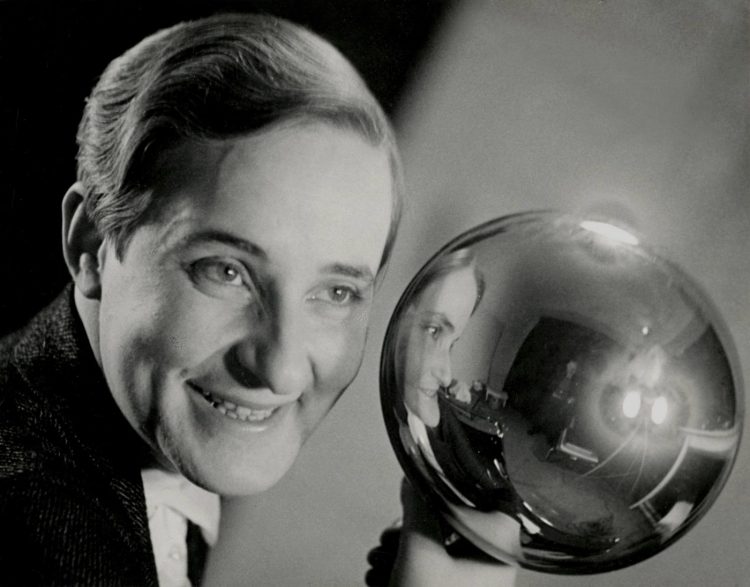

Frances Benjamin Johnston, Self Portrait, ca. 1890, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington

It’s a real joy to see, through an impressive number of photos dating from the very beginnings of the invention of photography through the Second World War, that the capacity of women, in the practice of this new medium, attained a degree of mastery and accomplishment equal to that of men. It was never in doubt, but elevating the visibility of their artistic output, so often ignored, renders the demonstration more impactful.

Starting with the appearance of the first daguerreotypes, female aristocrats and members of the bourgeoisie embraced photography. They learned different photographic techniques – daguerreotype, calotype, cyanotype – invented new procedures, developed their own film, did their own retouching. For the more well-heeled, it was a means of creative expression that allowed them a break from isolation, finding a means of existence outside of domestic and familial obligations, and to be affirmed as subjects empowered to observe, judge, and transmit. For others, it was a lucrative activity that allowed them to acquire a certain independence. Contrary to the fine arts tradition that confined women’s painting to the private sphere, professional and amateur photography groups, especially in Anglo-Saxon countries, opened their doors to female members. And in they flooded, displaying their work in various salons, exhibits, and publications organized by these societies.

Photography was, for many women, a collective activity that they practiced with other women, giving life to a new feminine solidarity: “I think that it is the duty of all woman photographers to help other women. Whenever it’s possible, drawing from their reservoir of concrete experiences. It is, now more than ever, in her power to demonstrate of what she is capable,” stated Catherine Weed Barnes in 1890.

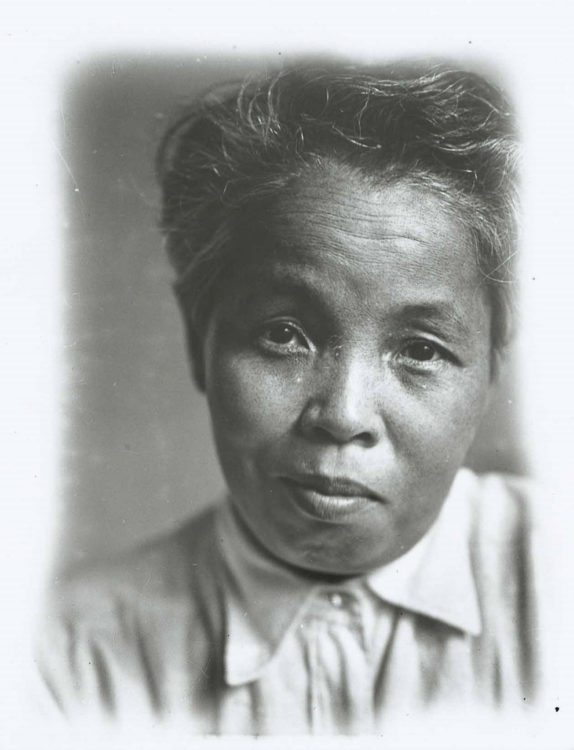

S. Hoare, Indigène des Marquises, 1880–1885, print on albumin paper, © Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques-Chirac/Photo Scala, Florence

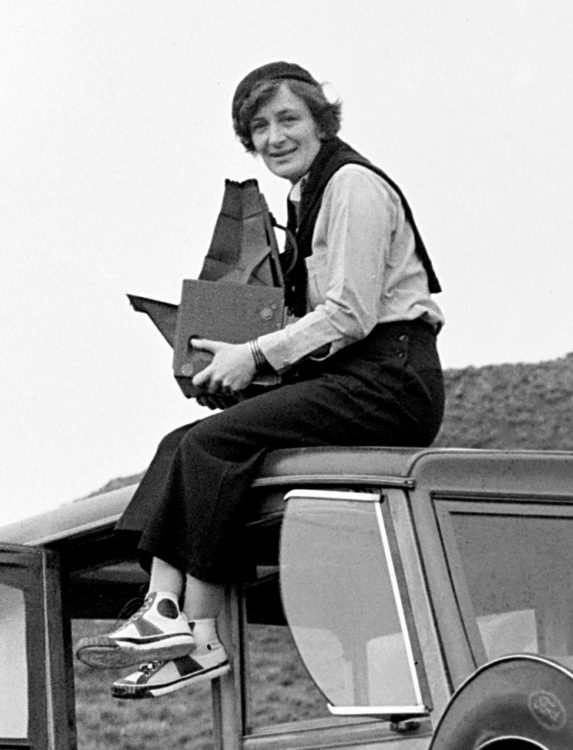

Women were very active and productive, recording their words in photo albums (Anna Atkins), and creating the first photo collages in photographic history (Georgina Louisa Berkeley). They experimented with all kinds of representation: portrait, self-portrait, landscape, still lifes and allegories; based in their own visions of femininity, maternity, virility, of couples and the family. They interrogated femininity and gender roles, immortalizing playful cross-dressing (Alice Austen, Julia Martin, Julie Bredt, Dressed as Men, 1891; Frances Benjamin Johnston, Self-Portrait as Male Cyclist, 1890–1900). They made their first forays into the nude genre (Imogen Cunningham, Nude Self-Portrait, 1906), forbidden to women in traditional fine arts practice at the time.

Christina Broom, Jeunes suffragettes faisant la promotion de l’exposition de la Women’s Exhibition de Knightsbridge, 1909, photomecanical print, © Christina Broom/Museum of London

Little by little, woman photographers became professionals. They opened studios specializing in portraiture and became photojournalists. They ran into their fair share of trouble in war-torn countries; ethnographic expeditions came together through their images of social or ethnic minorities, of education, or the drama of the first world war. The exhibit at the musée de l’Orangerie ends with the photography of Christina Broom, showing suffragettes demonstrating for women’s right to vote in 1909: the perspective of a woman on the struggle for women’s liberation.

The exhibit at the musée d’Orsay will be the subject of another article.

At the musée de l’Orangerie, from 14th October 2015 to 24th January 2016.