Focus

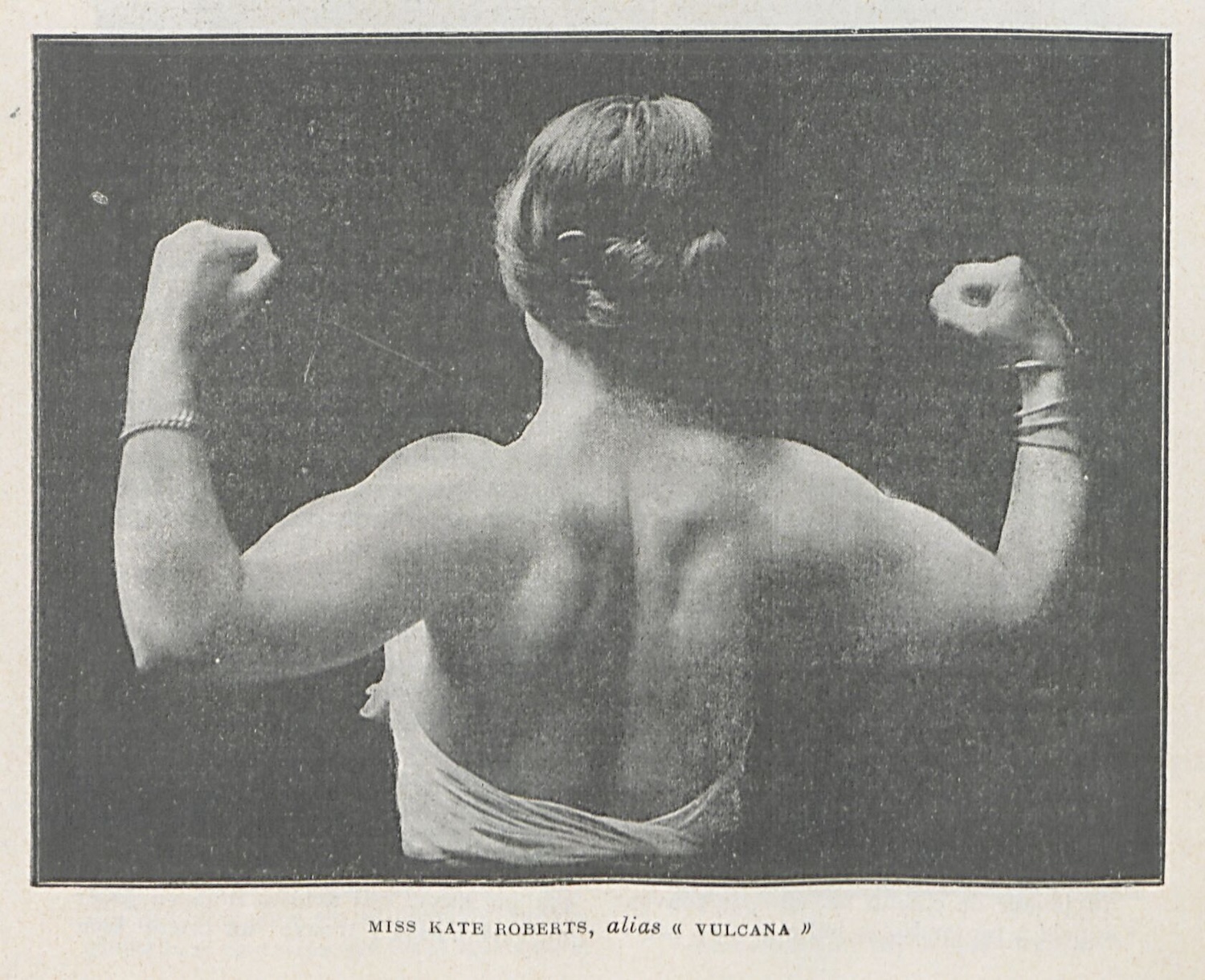

Miriam Kate Williams or Kate Roberts aka Vulcana, in STRONG, John, « Les femmes athlètes », L’Éducation physique, n°12, 30 September 1904, pp. 358

Let’s get straight to the point: modern sport was created by men, for men. It was in 1871, following the defeat by Prussia, that democratising sporting practice began in France. According to Thierry Terret, the “male community” had been undermined and was seeking to recapture its virility. Women were evidently unwelcome in this masculine history.

There were sporting women at the turn of the 20th century, even professional ones – cyclist Amélie Le Gall, known as Mademoiselle Lisette, for instance. Nonetheless, women were excluded from such “virile” sports as boxing, allowed to participate only in amateur and exhibition sports. They were also relegated to performing sports as spectacle, with women wrestlers and strongwomen found in fairs and circuses. Despite their remarkable physiques, these women did not escape the constraints of gender categorisation: critics used the characteristics of their supposed eternal feminine to qualify their athletic work, in an endless aestheticisation.

Within the eugenic framework that prevailed at the turn of the 20th century, women were meant, above all, to be mothers. Sport carried with it a danger: its practice may turn them into men. Caricatures of the period reveal this fear of the virilisation of women and an “inversion” of genders and many works offer a fantasised vision of women’s sporting practice, oscillating between fiction, sexism and eroticism.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Natalia Gontcharova (1881-1962), Renée Sintenis (1888-1965) et Adrienne Jouclard (1882-1972) took up the motif of sport as they conducted visual research into light, movement and synthesis. Though their best-known of these works mostly feature men, other artists were depicting women. In 1927, as women such as Violette Morris participated in automobile competitions. Gerda Wegener (1886-1940) portrayed an elegant woman with cropped hair at the wheel of her car.

During the same decade, Claude Cahun (1895-1954) staged and photographed her body being trained to be a bodybuilder in a burlesque parody. Lotte Laserstein (1898-1993) met Traute Rose, who would become her principal model, and painted images of her athletic figure, which are not without a certain erotic ambiguity. In a similar vein, photographer Frieda Riess (1890-1955) exposed the muscular body of boxer Erich Brandl. Seen by women, these sporting bodies of a man and a woman emerge unprecedented from what Laura Mulvey termed, in 1975, the “male gaze”.

What we see here is the major role sport and art play as tools and laboratories that shape our imaginations. Recent studies that render visible women’s histories of art and sport are thus an essential undertaking. This allows us to reassess established norms and, as Florys Castan-Vicente describes it, call for changes to the definitions of sport (and art) to help us write a more inclusive history.

1894 — France | 1954 — Jersey

Claude Cahun

1898 — Prussia (now Pasłęk, Poland) | 1993 — Sweden

Lotte Laserstein

1881 — Russia | 1962 — France

Natalia Gontcharova

1888 — Poland | 1965 — Germany

Renée Sintenis

1935 — 1972 | Belgium

Evelyne Axell

1940 — Mexico | 2022 — Portugal

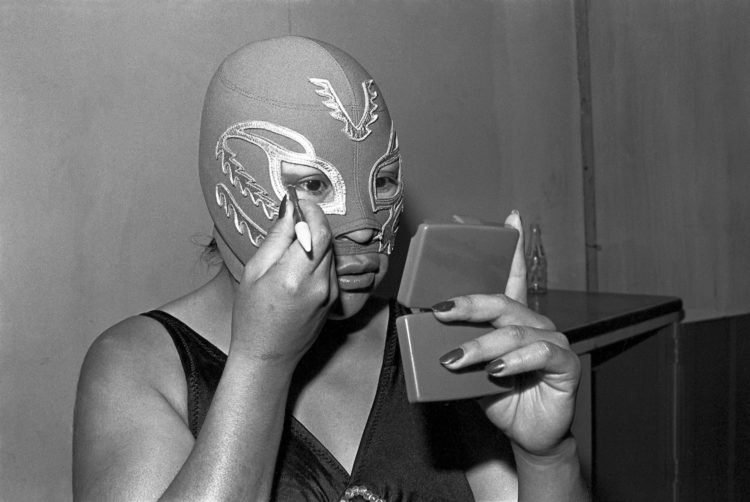

Lourdes Grobet

1918 — 1989 | United States

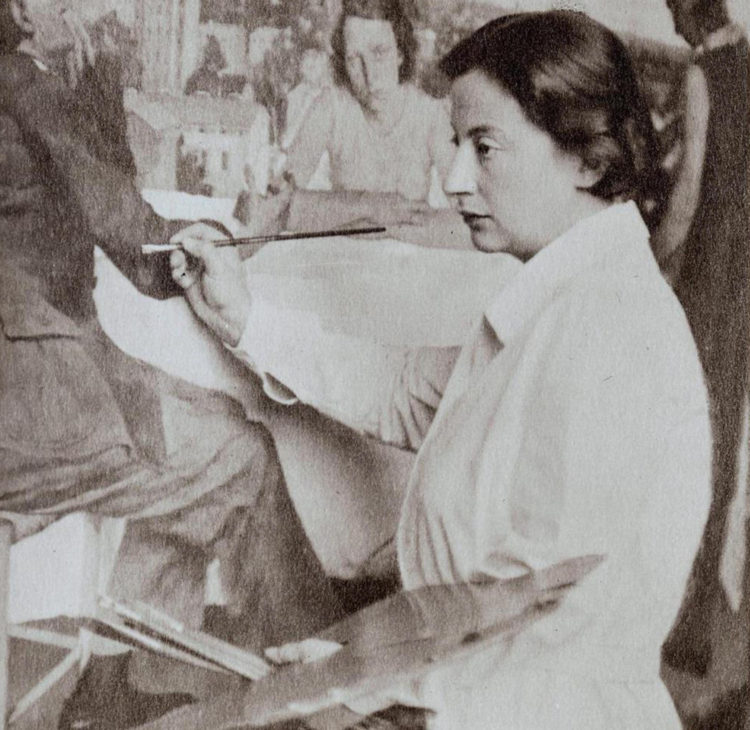

Elaine de Kooning

1898 — Poland | 1980 — Mexico

Tamara de Lempicka

1885 — 1940 | Denmark

Gerda Wegener

1944 | Chile