Research

Samia Halaby, Third Spiral with Dark Center, 1970, oil on canvas, 167.5 x 167.5 cm, private collection, courtesy of the artist © Samia Halaby

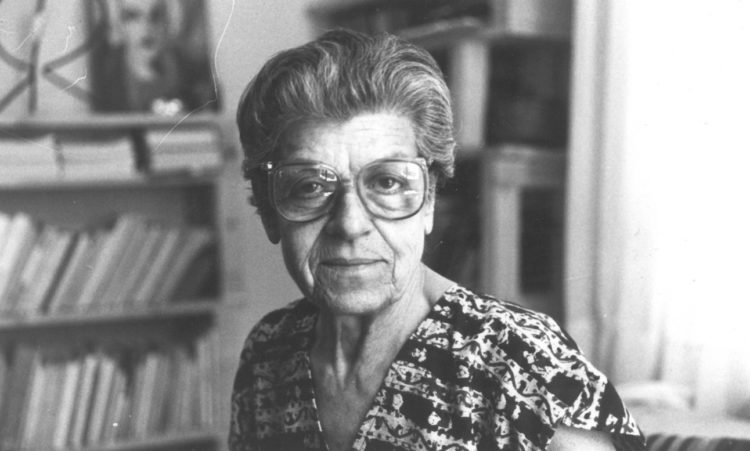

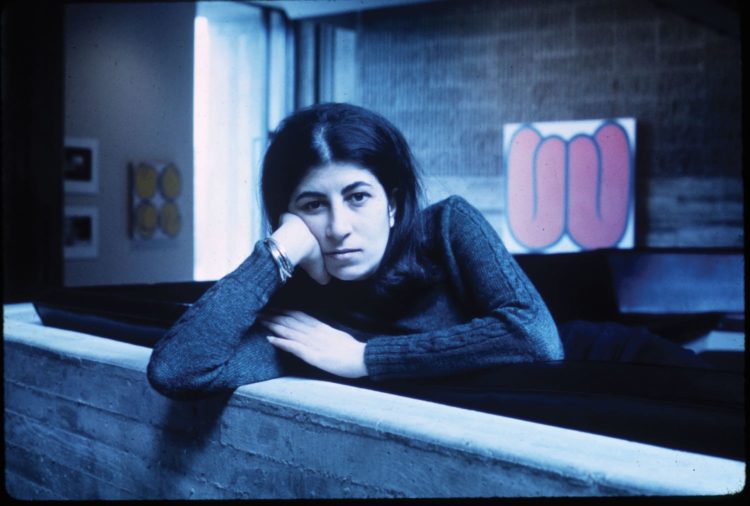

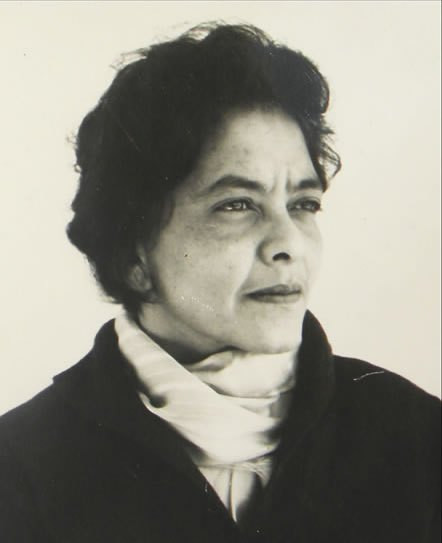

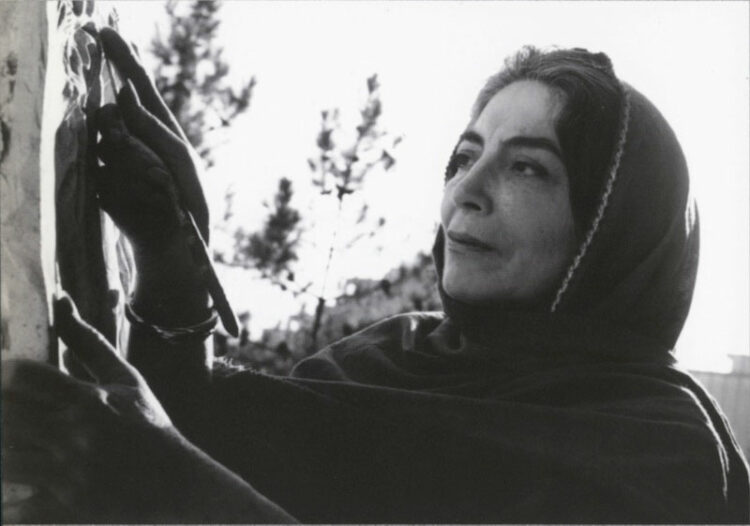

The years 2021 and 2022 have sadly witnessed the loss of three monuments of modern art from the Arab world: Etel Adnan (1925-2021), Gazbia Sirry (1925-2021) and Mona Saudi (1945-2022). Each of them has played a major role in opening new paths for engaging with contemporary art practices. Gazbia Sirry by defining the contours of Egyptian modern art, and Mona Saudi and Etel Adnan by engaging with abstraction, in Jordan and the United States, respectively. Their individual approaches have in common their engagement with international pictorial expressions, while at the same time referring to belonging or their diasporic condition.

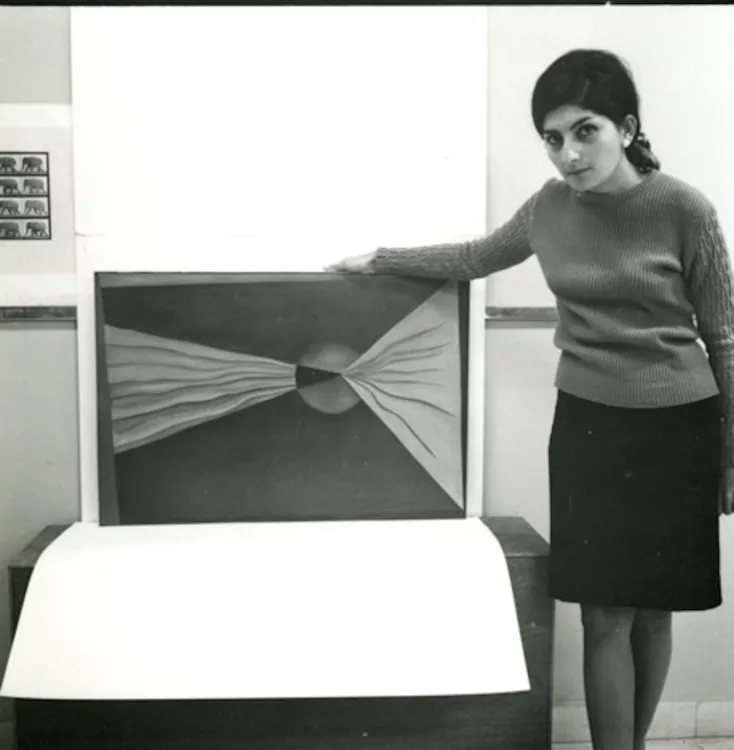

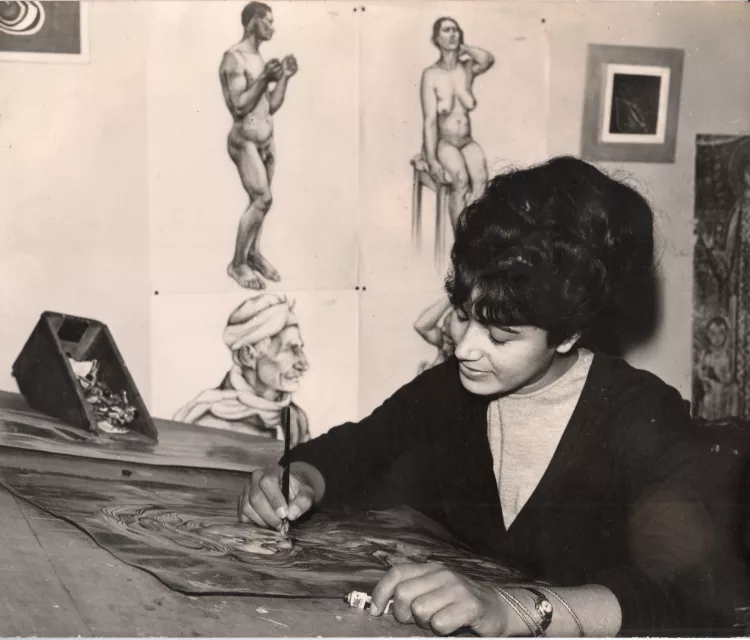

When I once asked Etel Adnan if it had been difficult to be a Lebanese women artist in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, she simply answered with a grin that it was certainly more challenging to be a women abstract artist than an Arab at the time. How then, did abstract women artists such as Adnan, Saudi, but also the Lebanese Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017) and the Palestinian Samia Halaby (born 1936), who all share a commitment to activism, deal in their work with the then Western-male-dominated discourses of abstraction (fig. 1)? More specifically, what counter-narratives to the dogmatic Greenbergian narrative on abstract art, its purity and the self-referentiality of painting does their work convey?

Fig. 1. Saloua Raouda Choucair, Dual, 1975-1977, aluminium, brass, 10 x 12 x 7 cm, Paris, Centre Pompidou – Musée National d’Art moderne – Centre de Création Industrielle, photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Bertrand Prévost © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

These questions bring to the fore the necessity of seeking alternative methods and historiographies in the writing of more inclusive stories of art, in particular regarding women artists from the Arab world. Indeed, especially when it comes to abstraction, and because its discourse has been so influential in Western modernism, the epistemic traps are manifold.

Abstract artists, such as Adnan and Halaby, have in common that they were born and grew up during the French and British mandate period and have therefore witnessed the major political, social and cultural transformations generated by decolonial movements in the region. They also share the lived experience of conflict, war, migration and exile, marked by the loss of a homeland and preservation of cultural memory, which echoes on different levels in their works. As artists of the diaspora, they have been recognised relatively late in their careers, possibly because their practice did not explicitly reflect their Arabness, neither did it find a legitimate place in the historiography of movements that constituted Western modernism. Besides, by engaging with the Western pictorial tradition of abstraction without resorting to markers of authenticity, their works have also been excluded from the national narratives of Arab modern art. They have nevertheless been absorbed by the global art market and its homogenising discourses. Thus, the challenge is to relocate their work in the context of connected histories of abstraction (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Etel Adnan, Untitled, 2010, oil on canvas, 26.8 x 32.8 cm, Paris, Centre Pompidou – Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre de Création Industrielle, photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Philippe Migeat © Etel Adnan

In recent years, global abstraction has received increasing attention in scholarship and international exhibitions have contributed to defining the contours of a more inclusive history of abstract art.1 While the number of women from the Middle East represented in international exhibitions and biennials as early as the 1950s shows that they were not necessarily unrepresented in comparison to their European or American counterparts,2 the fact these artists were both women and Arab nevertheless led to their double exclusion from the traditional canon and, in particular from abstract art.

In order to follow the migration of aesthetics and art-historical discourses and the effects of their translocation one may reflect, for instance, on a notion that is central to both Islamic and Western abstraction: the ornament. Adnan and Halaby’s works challenge the discourse about the purity of abstraction by referring to multiple clashing sources, but yet not incompatible, such as the decorative ornaments and marble panels of Islamic monuments, Russian Constructivists and action painting. In that sense, their work defies the idea that there would be a universal way of considering abstraction and goes precisely against the grain of the elimination of “subject matter, be it sentimental, documentary, political, sexual, religious”3 that once constituted the ideological basis of Western abstract art.

The links between abstraction, ornament and Islamic art have been theorised since the nineteenth century through major Western works that circulated globally, such as Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament (1856) or Alois Riegl’s works on the arabesque in his Problems of Style: Foundations for a History of Ornament (1893, published in English in 2018).4 These titanic research projects about the origins and history of the ornament also contributed, on a certain level, to reducing the field of Islamic art to that of the ornament, a prerogative that was also to be instrumentalised as a racial prejudice.5 The arabesque was probably amongst the most popular Islamic patterns which was universalised by such theories. And it would receive its coup de grâce after Adolph Loos published his infamous Ornament and Crime in 1913, which deemed the arabesque incompatible with modernism, condemned it to the realm of the decadent, the other and, subsequently, the feminine.

However, studies of Islamic aesthetics have shown that since the classical Islamic age the reception of the ornament and notably of the arabesque differs on many levels in Muslim countries from that of Western aesthetic theories.6 In that perspective, it is possible to understand how modern abstract artists from the Arab world, through references to decorative patterns and ornamental motives of Islamic art and architecture, redeemed the ornament by giving it agency while engaging with the mediums and pictorial tradition of Western art.7

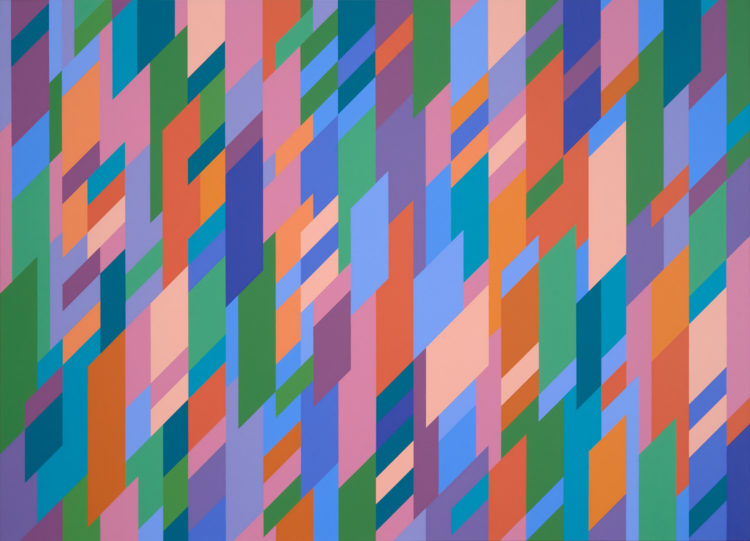

Fig. 3. Samia Halaby, Third Spiral with Dark Center, 1970, oil on canvas, 167.5 x 167.5 cm, private collection, courtesy of the artist © Samia Halaby

For instance, Samia Halaby’s work Third Spiral with Dark Center, painted in 1970, which could easily be identified as Western and masculine, yet weaves deep connections to Islamic arts, ornament, and traditional craftsmanship. Reflecting the artist’s vibrant energy and rigorous attention to geometric arrangements, this work draws inspiration from both Kazimir Malevich and the Russian avant-garde, while referencing the decorative elements of the polychrome marble inlay of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. This spiral infuses an ornamental reference symbolically charged with meaning and associated with the notion of territory (fig. 3).

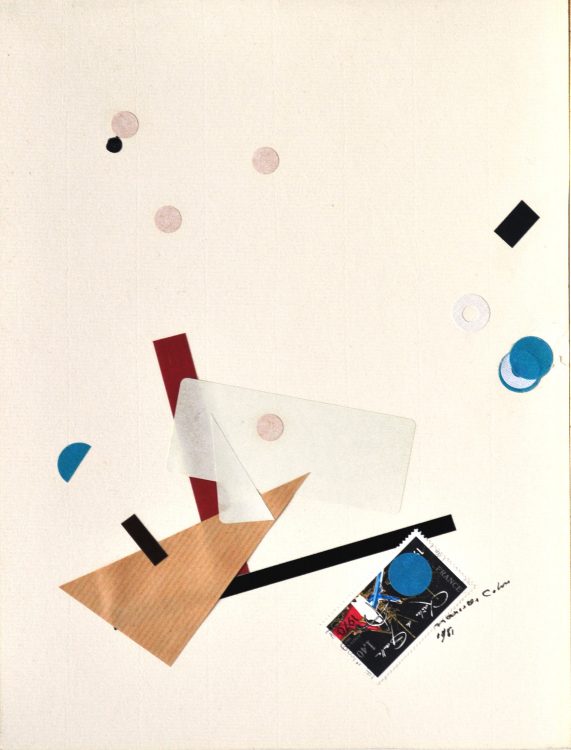

Another important aspect of the recontextualisation of abstraction is the examination of the relationship of modern abstract works with Arabic calligraphy, poetry and the artist’s book. Interestingly, many women abstract artists from the Arab worlds started experimenting with Arabic calligraphy while living and working in the United States. This was the case, for instance, of Etel Adnan who started to copy Arabic classical poems by hand when she was studying at the University of California in Berkeley. Similarly, the Iraqi-born artist Madiha Omar (1908-2005) integrated Arabic letterforms to her work while studying at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, DC. During that time, she published an important text on the use of Arabic calligraphy titled Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art (1949).8 But what was the impact, for instance, of the Color Field movement on her work? How could calligraphic modernism also known as the Hurufiyya movement (from the Arabic word harf, meaning the written word) connect to the Greenbergian discourses about abstraction?

While some of these artists are recognised internationally, notably on the global art market, their subjective experience and the analysis of their practice has been undermined and deserves further inquiry. Furthermore, their engagement with Abstract Expressionism could also imply strategies of resistance and emancipation, not only from the traditional canon of Western art but also from discourses of global art that tend to conceal difference and particularisms. The work of abstract artists from the Arab world does not necessarily rely on the spectacularity of politicised aesthetic, it rather involves the subtle and more discreet but yet powerful critical potential of elements such as the ornament and their multiple genealogies. By doing so, these artists defy the implicitly monocultural narrative of abstraction and broaden its conventional definition.

For instance, the exhibition dedicated to women abstract artists held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris: Christine Macel and Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, eds., Elles font l’abstraction (exh. cat. Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2021). Another exhibition focusing on Arab abstract artists was organised by the Barjeel Art Foundation at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University: Lynn Gumpert et al., Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s (exh. cat. Munich: Hirmer, 2020).

2

Nadine Atallah, “Have There Really Been No Great Women Artists? Writing a Feminist Art History of Modern Egypt”, in Under the Skin: Feminist Art and Art Histories from the Middle East and North Africa Today, eds. Ceren Özpınar and Mary Kelly (Oxford: The British Academy/Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 14-15.

3

Alfred H. Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1938), p. 13.

4

See the substantial volume by Gülru Necipoglu and Alina Payne, eds., Histories of Ornament: From Global to Local (Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 2016).

5

Finbarr Barry Flood, “Picasso the Muslim: Or, How the Bilderverbot Became Modern (Part 1)”, Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 67/68 (2016/2017): pp. 42-60; Christian Kravagna, “Adolf Loos and the Colonial Imaginary”, in Colonial Modern. Aesthetics of the Past – Rebellions for the Future, eds. Tom Avermaete, Serhat Karakayali and Marion von Osten (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2014), pp. 245-261.

6

Puerta Vílchez and José Miguel, “Aesthetics in Arabic Thought from Pre-Islamic Arabia through al-Andalus”, in Handbook of Oriental Studies, The Near and Middle East, vol. 120, trans. Consuelo López-Morillas, ed. Renata Holod (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 1-22.

7

Oleg Grabar, The Mediation of Ornament (Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1992).

8

The manifesto was reprinted in Charbel Dagher, Arabic Hurufiyya: Art and Identity Milan: Skira, 2016), 136-137, and in Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers and Nada Shabout, eds., Modern Art in the Arab World. Primary Documents (New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 2019), pp. 139-142.

Nadia Radwan is Assistant Professor of World Art History at the University of Bern. She has been a researcher and teacher at the American University in Cairo, the American University in Dubai and the University of Zurich. Her research focuses on Middle Eastern art and architecture (19th-20th century), non-western modernisms, Arab feminisms, nostalgia and orientalism, and the global museum. Her book Les modernes d’Égypte was published in 2017 (Peter Lang) and she is currently working on her second book about the politics of global abstraction. She is the co-founder of Manazir.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Nadia Radwan, "Women Artists from the Arab World: On the Discourse of Abstraction and Other Misconceptions." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/femmes-artistes-du-monde-arabe-sur-le-discours-de-lart-abstrait-et-autres-idees-recues/. Accessed 10 February 2026