Research

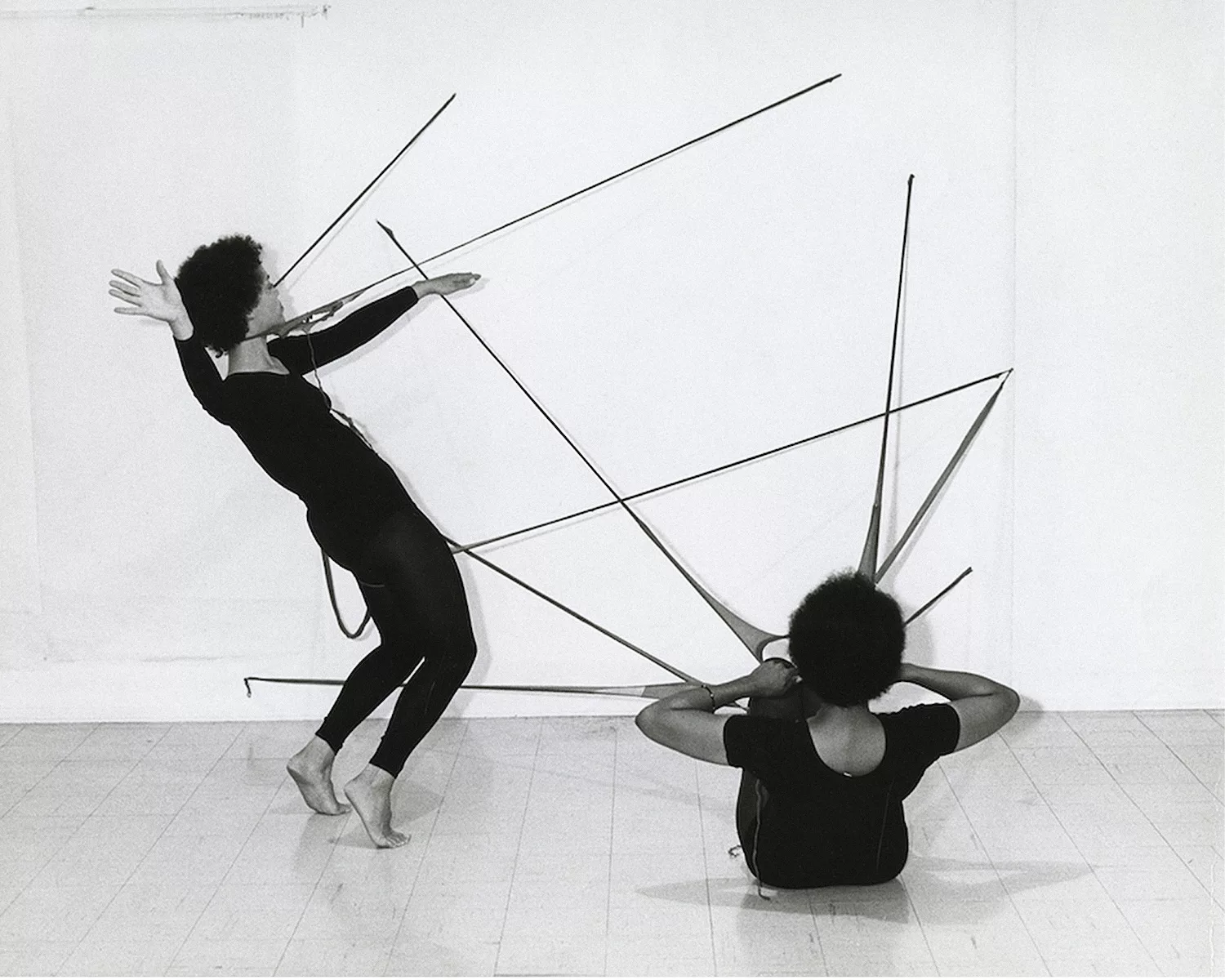

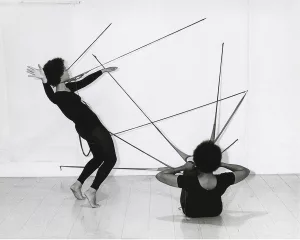

R.S.V.P. activated by Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger at Pearl C. Woods Gallery, Los Angeles, May 1977, © Photo: Harmon Outlaw. All rights reserved

This article extends a lecture series on African American art led by Laureen Picaut at the Centre Pompidou-Metz between 2023 and 2025. Through the study of major figures such as Barbara Chase-Riboud, Suzanne Jackson, Lorraine O’Grady, Betye Saar, Adrian Piper and Senga Nengudi, the series explored experimental artistic practices developed on the margins of canonical Western art history narratives.

From the very title of her iconic R.S.V.P. series – an acronym for Répondez s’il-vous-plaît – initiated in 1975 at the birth of her son, Senga Nengudi (b. 1943) calls for an active response. Her installations, composed primarily of nylon tights – an emblematic material in her practice – interweave matter, body and gesture to create spaces conducive to encounter. Amongst the many possible approaches to her work, two key perspectives stand out: the participatory dimension of her practice, rooted in her artistic collaboration with Maren Hassinger (b. 1947), and the memorial charge embedded in her sculptural installations.

Born in Chicago, S. Nengudi trained in both sculpture and dance, notably at California State University, Los Angeles. Resistant to any form of categorisation, her practice developed within the sociopolitical context of the USA of the 1960s and 1970s – a period shaped by the civil rights movement, the rise of Black Power and an artistic scene at the intersection of formal experimentation and political engagement. These years also saw the rise of a hegemonic feminism grounded largely in white experiences, prompting many African American women artists to articulate an intersectional response. Echoing the intellectual framework of Black feminism, they denounced the overlapping oppressions of gender, race and class – translating these lived experiences into both their artistic practices and collective actions. In a 2018 lecture at the Roski School of Art and Design in Los Angeles, S. Nengudi emphasised: “I felt marginalised by the feminist movement because it almost felt like some of us were tools to be used as opposed to co-participants in creating something. It was sort of like bean counting, the sense of diversity and inclusion felt like it was coming from that, as opposed to a genuine sense of interaction and co-creating.”1

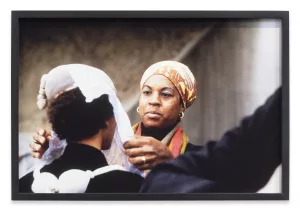

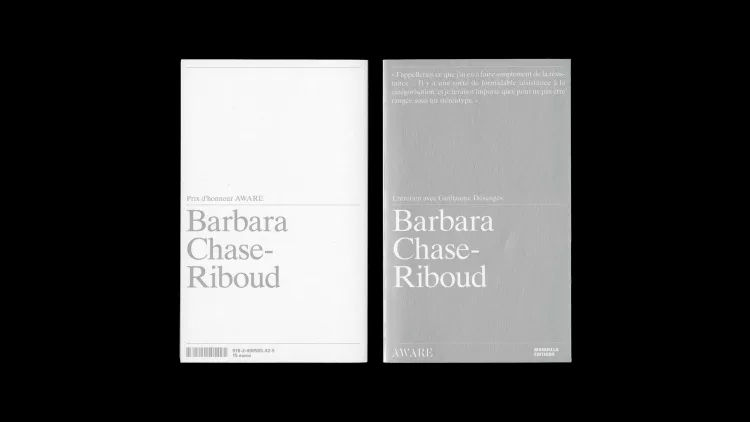

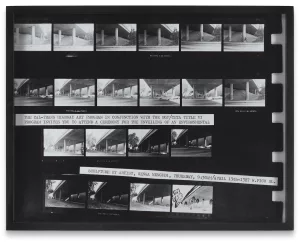

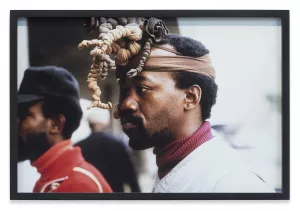

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978, 10 c-prints and contact sheet, documented by Kwaku Roderick Young, dimensions variable, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

At the same time, S. Nengudi’s work engages with major aesthetic debates of the second half of the 20th century – conceptual art, performance and post-minimalism – while distinguishing itself through a decidedly experimental and collaborative approach aimed at subverting the objectification of Black bodies. In Los Angeles, she joined the Studio Z collective. Alongside M. Hassinger, David Hammons (b. 1943), Houston Conwill (1947–2016) and Roderick Kwaku Young (dates unknown), she explored transdisciplinary forms and intervened in unexpected public spaces – car parks, vacant building plots, pavements and parks – transformed into ephemeral stages. In 1978, the group staged Ceremony for Freeway Fets, a landmark performance that became emblematic of their collective and experimental practice. Presented beneath a motorway junction on Interstate 10, along Pico Boulevard in central Los Angeles, the performance blended ritual elements drawn from Yoruba culture with Japanese dance-theatre, which S. Nengudi first encountered in 1967 during a year of study at Waseda University in Tokyo. The piece inaugurated Freeway Fets, a sculptural installation by S. Nengudi composed of her signature materials – nylon tights and sand – arranged around the motorway’s concrete pillars. She envisioned the work as a symbolic device for reconciliation between Black men and women, with D. Hammons embodying the masculine, M. Hassinger the feminine and S. Nengudi herself representing a unifying spirit.

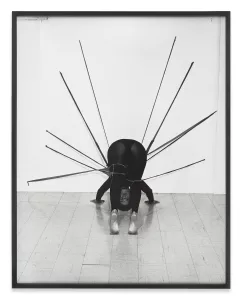

Maren Hassinger, On Dangerous Ground (artist in studio), April 1981, © Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA, Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC

Maren Hassinger, Leaning, 1980, Wire rope and wire, 40,6 cm high each (32 units), 10,96 m dia. installation, In the collection of The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC

Maren Hassinger, Field, 1983, Concrete and wire rope, 121,9 × 457,2 × 457,2 cm, Installation view, Maren Hassinger, Dia:Beacon, December 2023 – December 2024, Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC

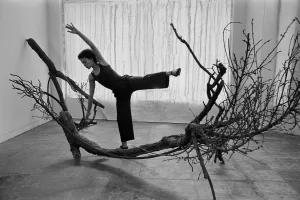

At the heart of this group dynamic, the relationship between S. Nengudi and M. Hassinger holds a central place. Together, they developed a practice in which trust and friendship became the driving forces of a shared artistic inquiry. Their creative bond goes beyond mere collaboration – it embodies a form of affective resistance that deeply informs both of their bodies of work. Trained in both dance and sculpture, in the 1970s M. Hassinger began to create work shaped by the transformation of industrial materials – particularly wire rope, which she manipulated through twisting, braiding or fraying to explore its sculptural possibilities. She also incorporated natural elements to create structures evoking roots, foliage and other organic forms. In M. Hassinger’s practice, as in S. Nengudi’s, repetition, performative activation and the use of everyday and organic materials – nylon tights, sand, plastic, paper, branches and leaves – serve as both aesthetic and political strategies, embedding intimate and collective experience into form.

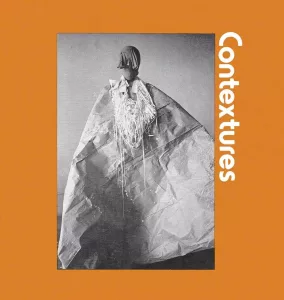

On the East Coast, in New York, African American gallerist and art historian Linda Goode Bryant played a pivotal role in the recognition of S. Nengudi’s work, exhibiting it as early as 1977 at Just Above Midtown (JAM), the gallery she founded in 1974. As a laboratory for the African American avant-garde, JAM became a space of experimentation that fostered visibility, professionalisation and dialogue amongst artists – including Lorraine O’Grady (1934–2024) and Howardena Pindell (b. 1943). Through her curatorial and editorial work, L. Goode Bryant championed artistic practices that she theorised alongside art historian Marcy S. Phillips in Contextures (1978), a self-published book offering a rereading of American abstraction through the prism of African American creation. The practices grouped under this aesthetic engage with ‘remains’ – manufactured objects, industrial scraps or organic fragments including plant material and hair – imbued with collective and intimate memory with political, spiritual, symbolic or esoteric resonances. S. Nengudi’s work exemplifies this approach so fully that a photograph of a costume study for the performance Mesh Mirage (1977) is featured on the book’s cover.

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. (Performance Piece), 1977, silver gelatin prints, triptych, documented by Harmon Outlaw, overall dimensions 300.8 x 104.1 cm, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery, © Photo : Harmon Outlaw

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. (Performance Piece), 1977, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. (Performance Piece), 1977, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. (Performance Piece), 1977, Courtesy Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery

The R.S.V.P. series aligns itself with this theoretical lineage and embodies a collaborative reflection shaped by care, reciprocity and attentiveness to the other. It renders tangible a memory of the body – both individual and collective – materialised through the use of nylon tights: a material at once banal and intimate, capable of articulating internal tensions – the elasticity of skin, the plasticity of flesh and the resilience of the psyche. The artist explains: “I very much like the idea of used pantyhose because I felt as though somehow they were infused with the energy of the woman that wore them. And when placing sand in the pantyhose, there was a sense of sensuality, which I also wanted to express with these pieces. […] I was fascinated in how resilient the body was and I really wanted to somehow duplicate that experience. I also was dealing with the idea of the female psyche – that your psyche can stretch, stretch, stretch and come back into shape”.2 Thus S. Nengudi explores the dispossession and resilience of bodies through sculptural arrangements – pendulous, erect, stretched, knotted and sand-filled forms. The tights mimic viscera, skin and flesh, evoking both softness and rupture, vulnerability and strength. In R.S.V.P., the Black woman’s body becomes the very ground of the work: “The body can only stand so much push and pull until it gives way, never to resume its original shape. After giving birth to my own son, I thought of Black wet-nurses suckling child after child – their own as well as those of others, until their breasts rested on their knees, their energies drained. My works are abstracted reflections of used bodies.”3 By layering the personal experience of motherhood with the historical reality of Black women’s systemic exploitation, S. Nengudi invokes an embodied, visceral memory akin to what art historian Rizvana Bradley has termed transferred flesh: a displaced, fluid flesh, infused into both material and gesture.

R.S.V.P. activated by Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger at Pearl C. Woods Gallery, Los Angeles, May 1977, © Photo: Harmon Outlaw. All rights reserved

R.S.V.P. activated by Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger at Pearl C. Woods Gallery, Los Angeles, May 1977, © Photo: Harmon Outlaw. All rights reserved

Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P. (A performance piece) performed by Maren Hassinger as part of Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art at the Walker Art Center, 2014, © Photo: Gene Pittman

The first activation of R.S.V.P. took place in 1977 at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery in Los Angeles. The surviving photographs form a precious archive of this foundational performance. These images capture M. Hassinger’s body mirroring the symmetry of the stretched nylon, suspended in a constrained motion – wavering, and gently supported by S. Nengudi in a gesture of care and co-presence. One final shot shows both artists seated, in a moment of rest. Seemingly outside the frame of performance, this scene, included in the photographic archive, testifies to a shared moment that extends the work beyond its material form. These photographs make evident that the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of S. Nengudi’s practice are rooted in an ethics of relation – shaped by collaboration, listening and interdependence. Over the decades, R.S.V.P. has been reactivated in new contexts, each time affirming with greater force its relational dimension. In 2012, as part of the exhibition Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, S. Nengudi and M. Hassinger performed together nearly forty years after their initial collaboration. In a reciprocal listening, M. Hassinger’s body moves in dialogue with the nylon forms, and is extended by the attentive presence of S. Nengudi, who accompanies her gestures by delicately placing the tights on her body.

Maren Hassinger, Tree Duet I, 5617 San Vicente Blvd, Los Angeles, c. 1977/2025, silver gelatin print, 50,8 × 76,2 cm, © Photo: Adam Avila. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC

Exhibition view, Maren Hassinger: We Are All Vessels, Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC, April 2021 – June 2021, © Photo: Adam Reich, Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC

This participatory logic continued in A Response to Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P. Performance Piece, presented in the Grande Nef of the Centre Pompidou-Metz in May 2025. A performer and a cellist – often called upon as a duo – initiated a collective activation: the sand-filled tights were stretched and gradually connected to the audience, who were invited to physically interact with the installation, which became an extension of their bodies. Some pulled, others released. These simple yet charged gestures formed a shifting network, a collective organism – a shared flesh. A temporary community emerged, in which every presence reshaped the structure of the piece. This activation resonates with S. Nengudi’s and M. Hassinger’s own words: “It’s very much getting a relationship with the piece, being a part of the piece, seeing what the piece wants you to do, and répondez s’il-vous-plaît! It’s a back and forth, back and forth that occurs. […] Each one is sensitive to the other, in this case the material to the activator, and they respond and then it opens up from there. […] I guess it would be like having a partner: give and take.”4

Exhibition view, Las Vegas Ikebana: Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi, at the Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery at Reed College, Portland, Oregon [February 15 – May 19, 2024], © Photo: Mario Gallucci

Exhibition view, Las Vegas Ikebana: Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi, at the Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery at Reed College, Portland, Oregon [February 15 – May 19, 2024], © Photo: Mario Gallucci

S. Nengudi’s work displaces the traditional boundaries of sculpture by asserting relation as a condition of creation: it is never an autonomous object, but something that unfolds through exchange – at the heart of an embodied reciprocity where a politics of attention, presence and support takes root. Extended through shared gesture, the R.S.V.P. series generates potential encounters – between bodies, memory and imaginaries – operating as spaces of repair.

From 2024 to 2026, the exhibition Las Vegas Ikebana: Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi is presented at the Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery and at the Columbus Museum of Art at The Pizzuti. It is accompanied by the first comprehensive monograph dedicated to the collaborative practice of M. Hassinger and S. Nengudi.

Nengudi, Senga, “ROSKI TALKS: Senga Nengudi”, YouTube, 2018, 12:02 – 12:44, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKy-wDB9f54

2

“Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces”, MoMA, 2022, https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/326/4253

3

Nengudi, Senga, Senga Nengudi, exh. cat., Dominique Lévy Gallery, New York (September–October 2015), Dominique Lévy Gallery, 2015.

4

“On Art and Collaboration: Artist Talk with Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi”, YouTube, 2020, 24:45 – 28:35. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofOu36sNXFY

Laureen Picaut is an independent curator and art historian. Her research focuses on contemporary African American experimental and performance practices, exploring notions of intersectionality, collaboration and audience participation. She has worked with the Centre Pompidou-Metz, the Barbican and MO.CO., contributing to exhibitions such as Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics; Possédées: Déviance, performance, résistance; Lacan, the Exhibition; Louise Nevelson: Mrs. N’s Palace; and Dimanche sans fin as part of the curatorial teams.

Laureen Picaut, "Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger: Embodied Reciprocity." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/senga-nengudi-et-maren-hassinger-reciprocites-incarnees/. Accessed 12 February 2026