Interviews

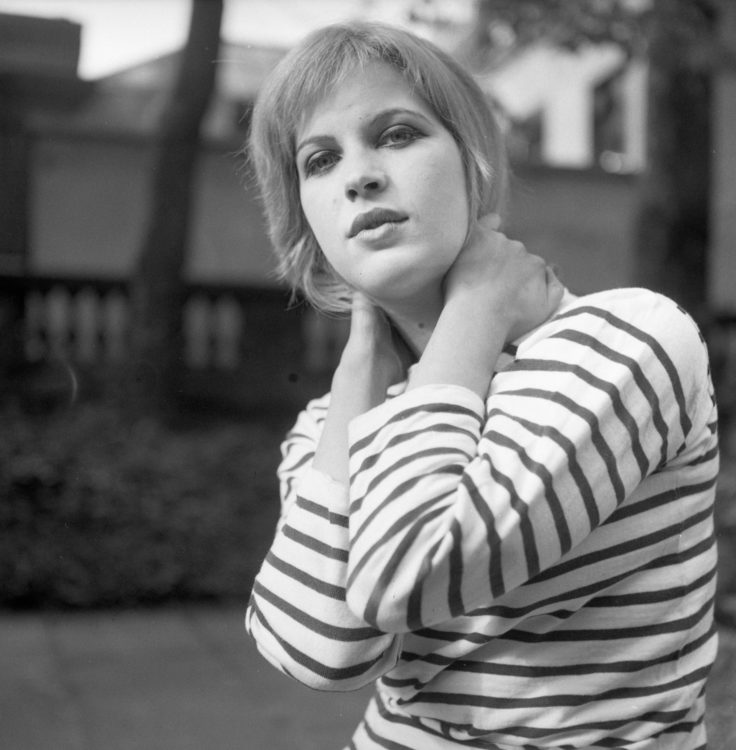

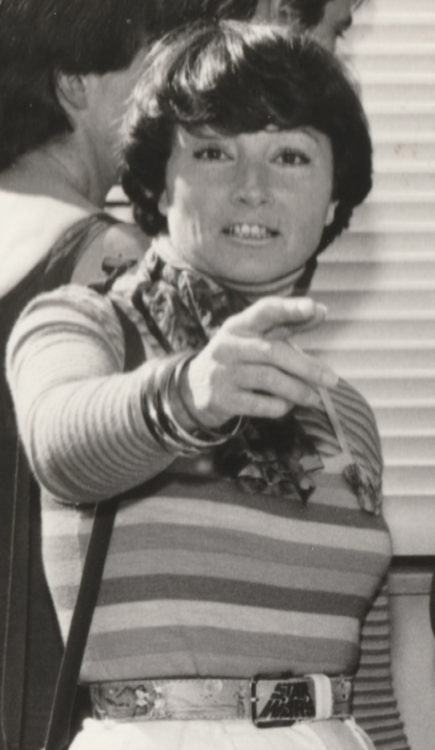

Exhibition view Pop Impact: Women Artists, Maison de la Culture de Namur, Sylvie Fleury, Evelyne Axell, © Photo: Ch Pierlot

An interview with Isabelle de Longrée, associate curator (together with Jean-Michel François) of the exhibition Pop Impact: Women Artists, held at the Maison de la Culture de Namur (17 October 2015–14 February 2016)

Annalisa Rimmaudo: Pop Impact courageously brought together the work of seven women artists, including one or two from Belgium: Evelyne Axell, Pauline Boty, Jann Haworth, Martine Canneel, Alina Szapocznikow, Niki de Saint Phalle and Sylvie Fleury. In tandem, just a few miles away, in Brussels, the ING Art Centre was holding the exhibition Pop Art in Belgium! Why this infatuation with Pop in Belgium right now?

Isabelle de Longrée: For us it was important to mount an exhibition about Pop in Belgium! . We realized that a lot of artists had worked on Pop, one of them, needless to add, being Evelyne Axell, who was from Namur, and well known at the city’s Maison de la Culture (MCN). A major exhibition of her work was organized in 2004, at the MCN, at the Musée Rops and in the Detour gallery, at a time when she had almost been forgotten. The goal was to show that Belgian and Walloon artists had taken part in that movement. One of the briefs of our establishment is to show the work of Belgian artists. We very soon found out that the ING Art Centre had had the same idea at the same moment. We met to try and do something complementary, rather than both go in the same direction. At the centre of our project was Evelyne Axell, who was the major representative of Belgian Pop art, and a woman artist. With Virginie Devillez, one of the catalogue’s authors, we decided to deal just with women artists. We wanted to use the example of Axell, whose work was made public some time after her death—she died in 1972 at the age of 37—by selecting other women who had suffered from a lack of visibility, quite simply because they were women.

AR: Michèle Bastin and Martine Canneel, for example…

IDL: Yes, precisely. Then we had to undertake certain investigations, and we got in touch with the art historian Kalliopi Minioudaki, and we decided to use her essay published in Power Up,1 which struck us as significant, and translate it into French. Because all this work involving the rediscovery of women artists started in the Anglo-Saxon countries, and in the United States first and foremost, where it found much fertile terrain, as is shown by the recent show The World Goes Pop,2 which was held at Tate Modern in London. By way of that experience, we were also keen to bring all that thinking into the French-speaking world. So we then started looking for women who had been very active in the Pop movement in Belgium, artists like Martine Canneel and Michèle Bastin (even though the latter left Belgium very early on and moved to Quebec.)

AR: There was in fact an urgent need to extricate those women from oblivion. So how did you find them?

IDL: By asking art critics in Belgium, in particular Claude Lorent, who has always championed their work and who still finds it interesting and topical. Martine Canneel, who is still alive, became very involved in the exhibition. Our director, Bernadette Bonnier, found Michèle Bastin’s name in a dictionary of Pop art,3 but nobody knew her in Belgium. We managed to catch up with her. She’s been living for many years in Quebec, developing an unusual body of work by producing Pop works with a Surrealist touch.

Exhibition view Pop Impact: Women Artists, Maison de la Culture de Namur, Sylvie Fleury, Evelyne Axell, © Photo: Ch Pierlot

AR: I’ve been wondering about the presence of Sylvie Fleury, who belongs to a younger generation in relation to the other artists on view in the show.

IDL: When we decided to limit the theme to women Pop artists, we wanted to find a link with the present and offer a contemporary way of looking at the subject. On the one hand, there was the idea of proposing a re-reading of art history through women: Pop art was not something exclusive to men—there had been a feminist praxis, but no one said anything about it. On the other hand, we raised the issue of its topicality. For us, Sylvie Fleury is a neo-Pop artist who extends the questions posed by artists of the 1960s into a present-day context. She explores our globalized consumer society, which came into being in the 1960s, and which has reached an extreme degree of consumerism today. Through her works, she challenges the significance of brands, and the importance of luxury…

AR : She applies a different form or irony, and you feel that she is more independent than her predecessors, or, at the very least, the woman’s role in her works is different. She can allow herself to laugh at Warhol…

IDL : She’s probably benefiting from hindsight. Her first action, when she exhibited her shopping bags, was not understood. That ambivalent position with regard to consumerism was also the stance of the Pop artists. Meaning that they were against the consumer society, while at the same time being part of it. It wasn’t just criticism, it was also to do with being part of this machine which consumes and sells dreams. Fleury exhibited what she had bought that day.

AR: In Fleury’s works, perhaps the guilt connected with that ambiguity has vanished.

IDL: Yes. The work which really illustrates that tendency is Jann Haworth’s piece, in which she borrows a work by Severini and uses sequins (Severini: Spherical Expansion of Light, 1966, sequins on fabrics, 62 × 51.5 cm). That work dates back to the 1960s, whereas Jann Haworth tends to adopt a postmodern praxis, as it was applied in the latter half of the 1970s: taking a masculine work and feminizing it by using the instruments of the applied arts. It’s a very ironical work, it embodies in a way the manifesto of a feminist discourse on art.

Exhibition view Pop Impact: Women Artists, Maison de la Culture de Namur, Sylvie Fleury, Evelyne Axell, © Photo: Ch Pierlot

AR: What was the Pop network in Belgium? Who were the most important collectors and critics of women artists? Are their beneficiaries still active?

IDL: The show Pop Art in Belgium! tends to explore those aspects more, so we haven’t expressly dealt with them. What I can say is that, after her divorce from Leo Castelli, Ileana Sonnabend opened a gallery in Paris and encouraged that movement. There was also an emblematic exhibition in 1965 at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels4 which showed Belgian artists and Pop, and that inspired a whole generation. Obviously enough there were no women artists in that exhibition. But figures like Karel Geirlandt, erstwhile director of the Palais des Beaux-Arts, lent a lot of support to Evelyne Axell, and exhibited her work in that venue a few years later. He also approached Martine Canneel, and offered her a show at the Palais, but it didn’t come to anything because Karel suddenly died before the project took shape. Critics like Pierre Restany supported Niki de Saint Phalle and Evelyne Axell a lot. Needless to say, it was very hard for those women to make a mark for themselves, and be taken seriously, and all the rediscovery work, for example with regard to Evelyne Axell, was done after her death, by her husband Jean Antoine, who completely devoted himself to spreading the word about her oeuvre. Her son, Philippe, did likewise.

AR: What is it that hallmarks this female movement?

IDL : What emerges from the show and what hallmarks Pop is probably the use of new materials. This is what is expressed in Virginie Devillez’s essay.5 Those women artists were always being referred back to their condition as women, because of a male tradition in art. They have always been pushed away, out of the fields of painting and sculpture. By using those materials which had just appeared, and which hadn’t been affected by any critical apparatus, they managed to free themselves from the influence of men. By making works with fake fur, polyester and neon, they appropriated those materials for themselves. Martine Canneel, for example, about whom we know very little, used small plastic toys and objects which call to mind the North Sea. Behind the naïve imagery of her works, there’s a somewhat melancholy subtext about the violence of human beings, as well as an ecological message at a time when this issue probably didn’t have priority. Demain sera meilleur (Tomorrow things will be better, 1972) is an emblematic work because of its message, because of the use of artificial lights, and the colour, which hides a more sombre idea beneath a very joyful appearance. As in other Pop works.

Power Up: Female Pop Art, exh. cat., Vienna / Cologne, Kunsthalle / DuMont, 2010.

2

The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop was held at Tate Modern in London from 17 September 2015 to 24 January 2016.

3

José Pierre, Le pop art, Paris, Hazan, 1975.

4

Pop art, nouveau réalisme, etc., exh. cat, Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, 1965.

5

Virginie Devillez, « Evelyne Axell en compagnie. Être femme et artiste au temps du pop », Pop Impact. Women Artists, exh. cat., Namur, Maison de la culture, 2016, pp. 35–61.