Interviews

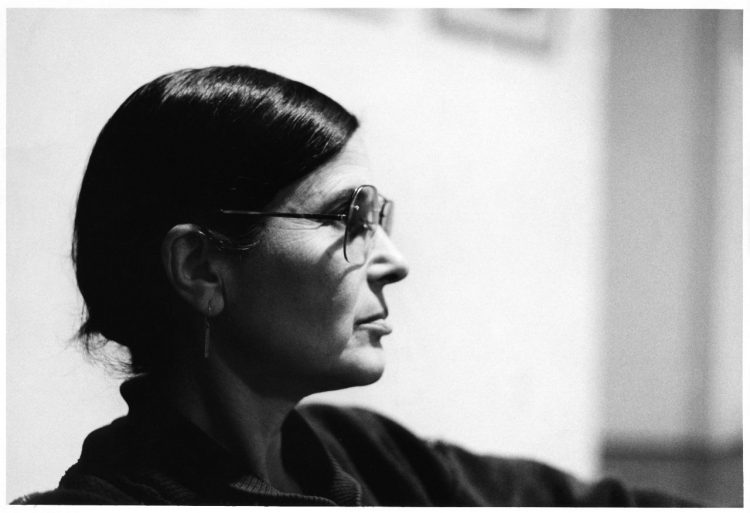

Mira Schor with Strange Fruit and Dicks, or The Impregnation of the Universe (both 1988, oil on multiple canvases, each work 112 x 53 in. [284.5 x 134.6 cm]), Lyles & King, New York, 2017 © Mira Schor.

Both as a painter and as an art critic, Mira Schor’s dual commitment has given her a singular place on the New York art scene. A student of Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago at CalArts, within the experimental Feminist Art Program, she finally chose a unique artistic path, operating at the crossroads of language and painting, which she transformed, with the support of her numerous critical texts, into a feminist medium in its own right. In 1986, she founded the journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G with Susan Bee. This interview is an opportunity to look back at her training, her career and her feminist commitment.

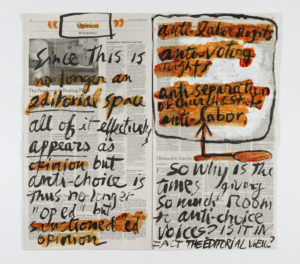

Mira Schor, New York Times Intervention #87, The New York Times, October 14, 2020 © Mira Schor.

Mira Schor, New York Times Intervention #121, The New York Times, December 9, 2021 © Mira Schor.

Matylda Taszycka: Recently, the political situation has had an important influence on you and your work. You wrote that painting is a “honey trap for contemporary discourse.”1 To what extent is the language of painting capable of representing contemporary historical reality?

Mira Schor: Let me go back to the “honey trap.” I used this expression in the 1990s, when I was working with the imagery of sexualized but also politicized gendered body parts. I was describing a studio visit with a curator and gallerist interested in political art, including racial and sexual issues. She was trying to figure out the paintings: “They’re political, but they’re paintings; they’re paintings, but political.” It was exactly what I was trying to achieve: something you would look at; not because you had been told to look at it or because it was illustrating a specific political situation, but because your eye would be caught by something expressive in the work; the paint was metaphorical in itself.

I spent the time from the summer before Donald Trump was elected through 2018 doing what I see as extremely political work, including about 150 drawings: I would read The New York Times and then do a drawing specific to a particular moment of outrage, sometimes quoting him, so some of those are filled with his crazy words. It was figurative in that there would be a sort of outraged mythological woman, screaming or whatever. I have continued a parallel practice of occasionally annotating and correcting the hard copy of the newspaper.

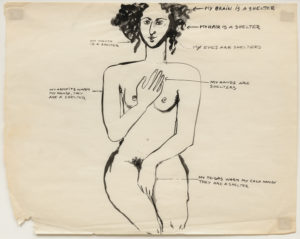

Mira Schor, Feminist Art Program, Class Assignment: Self Image, 1972, ink on paper, 18 ¾ x 24 in. (47.6 x 61 cm) © Mira Schor.

Mira Schor at Womanhouse with, from left to right, Miriam Schapiro, Judy Chicago and Christine Rush, Los Angeles, winter 1971/72 © Mira Schor.

M.T.: As a graduate student, you were a participant in the Feminist Art Program at CalArts (California Institute of Arts) in 1971-1972, under the direction of Miriam Schapiro (1923-2015) and Judy Chicago (b. 1939). In 1972, you took part in Womanhouse. You wrote that your education was doubly formative, marking you generationally and politically. What did this feminist education look like?

M.S.: I used to call it “bootcamp for feminists.” The goal was to use consciousness raising, feminist readings, the development of a history of women artists and a feminist art history to make young women aware of how they are raised into a complicity with their own oppression within patriarchy, to take the rose-colored glasses off, experiment with new materials, subjects and methods to make art that would reflect this new consciousness. It was not a “class,” it was a full-time commitment and a separatist program. No men allowed. There was a large common studio space allocated to the program, with a locked door. What we were doing behind it and the curiosity about it raised the feminist consciousness of the whole institution.

I was already aware of the exclusion of women artists from art history because I was steeped since childhood in the beliefs and mores of the New York art world. As an art history major at New York University, I studied with H. W. Janson, who wrote the then major textbook of art history, which left out all women. I didn’t want to be an art historian; I was identifying with the other side of the slide projector. I was lucky because I knew women artists: my mother Resia Schor (1910-2006) was an artist; in my late teens I befriended Pat Steir (b. 1940); I was good friends with the Pop artist Red Grooms (b. 1937) and his wife, the painter Mimi Gross (b. 1940); through them I met the painter Yvonne Jacquette (b. 1934). They were all so interesting, so serious about art, and so encouraging. When I got to CalArts, I was accepted and taken seriously as an artist.

At that time, my work was autobiographical. I was well-schooled in formalist issues both because of childhood and my college education. I understood what I was doing in terms of historical movements, why I was being rejected by the male power structure of the Greenbergian formalist school. I began to understand the role of Surrealism as a kind of covert feminist space (even though the guys who ran it were assholes). My works were representatives of my psychic autobiographical state. No other school would have allowed that approach.

Mira Schor, Goodbye CalArts, 1972, gouache on paper, 21 ½ x29 ½ in. (54.6 x 74.9 cm) © Mira Schor.

Mira Schor at Womanhouse, Los Angeles, February 1972, film still from Lynne Littman, Womanhouse is not a home, 1974 © Lynne Littman © Mira Schor.

Towards the end of my first year, I walked out of the Feminist Art Program and never came back. In Goodbye CalArts! (1972), I’m represented half-naked with a flower behind me, entering a social world. In that world, Fluxus was very important and had as much of an influence on the school’s ideology as on me in terms of attitude, emphasis on language, or even performativity. The last months I was there, I had designed a course called Picture Making, which turned out to be influential, and it started me on my own teaching life.

CalArts encouraged an opening up to different kinds of art practices, even without direct instruction. It was a non-academic academic experiment – the last expression of the spirit of ’68 in American art education. You didn’t have to become a performance artist to learn something from seeing Simone Forti (b. 1935) blindfolded in a hallway, being helped by a judo instructor to experiment with being sightless. I didn’t have to take a class with her; I could see her ideas in action. This enabled me to teach a fairly wide spectrum of students and gave me a basic awareness of the principles or possibilities of many different types of art.

M.T.: You write that teaching always relates to power and you talk about the contradiction between seduction and having an influence on students. After CalArts, what was your attitude towards this dominant position? What is your experience of influence, both as a teacher and as a student?

M.S.: Gross and Chicago had no model for what a feminist power structure would be, because the structure of authority in teaching was masculine and patriarchal. That model was a brutal one; if you stood up to it, then you were considered successful. As teachers, they tried to create a completely new educational atmosphere and philosophy, but also to shake up young women into seeing and giving up their patriarchal habits. It was intense.

It’s a privilege to have been able to participate in that. No school could be like that today; the last few years, we have been dealing with “triggering” students by the use of words they’re unhappy with. But working with J. Chicago, who was interested in performance, in a kind of psychodrama, was like one gigantic triggering event! One of the most important ideas of the Feminist Art Program was to try to develop, through the process of consciousness-raising, subject matter for art at a time coming after this Greenbergian moment where you could not have any subject matter other than form itself. We had sessions about many aspects of female experience: sexuality, body or rape. These were standard consciousness-raising subjects at the time and often brought out powerful emotions, which the faculty could not necessarily cope with adequately.

When I started teaching, my approach was informed by the model loosely based on a psychoanalytic interaction, something encouraged by the teacher I worked with after the Feminist Art Program, Stephan von Huene (1932-2000). I talk about the work with the student until something clicks. I do talk about it formally, because now, young artists often work with identity politics to the exclusion of any formalism. Some are so rigidly committed to representing a politics that they don’t even look at art, they’re just working from that identity. I’m trying to make them see their work as an artwork. But I try to be responsive to their personal concerns.

M.T.: To what extent has this type of experience had an impact on you, not only as an artist, but also as an art writer?

M.S.: We were taught that not only was it important to have produced artwork, but it was better if text existed about you. If discourse rejected you, you had to create your own.

Mira Schor, Slit of Paint, 1994, oil on canvas, 12 x 16 in. (30.5 x 40.6 cm) © Mira Schor.

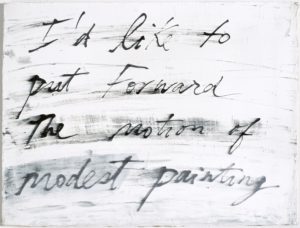

Mira Schor, Modest Painting, 2000, ink on gesso on linen, 12 x 16 in. (30.5 x 40.6 cm) © Mira Schor.

M.T.: The link between writing and painting is characteristic of your practice. Some of your paintings contain direct quotes from your critical texts. What brought you to this painterly work with language? Do you see it as directly related to your work as a writer?

M.S.: Language as image first appeared in my work in the late 1960s and then more seriously in the mid-1970s, long before I began to write about art. In the 1990s, when I started to use language as image again, I wrote: “I paint in English.” The meaning of what I’m painting is important. What I want is for the viewer to look at my work, even if they can’t decipher the meaning. I want them to think, “this is language” because everybody uses language; that’s the same motivation for the painting Slit of Paint (1994), reproduced on the cover of Wet. It’s important to have language, but also to recognize the language of painting as a language and see them together. My practice takes place at the intersection between “facture,” materiality, visual pleasure and conceptual linguistic content.

Modest Painting (2001) is the title of an essay and of a painting representing the first sentence of that essay.2 When Virginia Woolf wrote A Room of One’s Own (1929), women were not thought of as being filled with language, in the sense of concepts and literature or political language. I had this image of being a young woman sitting in a movie theater and you realize every woman in this room could drop out of public life and no one would ever care or be aware that they existed. Woolf writes about this accumulation of unrecorded lives. This book is one of the manifestos of my life.

In the 1970s, the text represented in my work was personal – letters that any woman would write, but they were mine, they were specific to me. Then I didn’t use writing as an image for a time and returned to it at the beginning of the 1990s with appropriated language because by that time I was immersed in the discourse of appropriation and in theoretical language. After my mother died, in 2007, there were no words to express how I felt, so I emptied the painting of language. And in the last few years I just put everything in, as necessary at that moment.

M.T.: You were trained by the second wave feminists at CalArts and at the same time, you never gave up painting; you defended it in your writing and your own practice. In the introduction of Wet you write that you are trying to put together feminism and formalism. So feminist theory and materiality are not exclusive for you?

M.S.: No, on the contrary. It’s funny: I’ve also been accused of being an essentialist, both because I talk about women and because painting itself is seen as essentialist, so I can’t win! I’ve always been aware of art historical movements and their politics. But I also grew up seeing art being made. There was more than one influence on me. From those formative years, I learned formal and material values, as well as the importance of narrative. Then as an art history student, I began to learn the context and the reasons why styles changed. Everything you thought you dislike as an artist at first can be useful, because it opens doors, whereas the things you love mostly gave you a foundation of loving art. One of the things I’m dealing with right now is working very large: it is harder for me to have physical involvement with material and to allow for accidents to happen.

M.T.: In 1986, you and the painter Susan Bee founded the journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G, which has now become a reference. What was its origin? Is it connected to the ability to write as an artist?

M.S.: The origin is “Appropriated Sexuality,” my first published essay, on the representation of women in David Salle’s painting (b. 1952), including Autopsy (1982).3 Over time a lot of people read the essay, including a number of the Guerrilla Girls, even though it was never published. S. Bee and I were in a little artists-critics group that met once a month to look at exhibitions’ slides and talk about them. One day in 1986 we just decided to publish a magazine, because October, a contemporary foil for our thinking, was so focused on photography, and we wanted to have an emphasis on art forms other than photography. We’re both feminists but wanted to also publish men. We decided not to print images on poor-quality paper, so writers had to describe artworks, and there were no ads. The first issue was self-financed, self-produced and self-distributed. I had no experience with small magazines, I didn’t know its history in the Abstract Expressionist movement and I wasn’t aware that some artists I knew, like Jack Tworkov (1900-1982), were incredibly good writers.

The reception was great, and the response to my piece was like a wildfire. The feminist art historian Carol Duncan called me up after that. We had to do another issue. After a year, we published the second issue, and then we came out in print twice a year. We gave voice to other artists and helped people publish their first art writing. After ten years, we stopped and worked for several years on getting a M/E/A/N/I/N/G anthology published (2000). By that time, my book Wet had come out.

Mira Schor, War Frieze X: It’s Modernism, Stupid, 1993, oil on multiple canvases © Mira Schor.

Mira Schor, War Frieze XII: Area of Denial-Egg, 1993, oil on multiple canvases © Mira Schor.

M.T.: The critics from October were not enthusiastic about contemporary painting, and predicted its death, favoring photography and video. Their approach was dominant in the United States when you started M/E/A/N/I/N/G. What was your position in the 1980s within this critical debate? Do you think they meant for this critique of representation to have a gender and anti-feminist dimension?

M.S.: Those guys were really against painting, and against a particular group of painters – some of the same people I was critical of – but they were critical of them again for that they were painting, not what they were painting. So, in the case of D. Salle, the problem was a betrayal of Baldessarian tenets, not how women were represented. The language with which art was written about shifted radically in the early 1980s to incorporate the influence of Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, as well as Marxist and anthropological language and so forth. It was different than the formalist language it replaced. Gradually some of this new language became mine as well, but oddly enough, that’s exactly when I started to use oil paint and returned to a more feminist focus. So, I was influenced as an artist by the discourse I was involved with as an art writer. I agreed with much of Benjamin D. Buchloh’s critique of Neo-Expressionism, just not his critique of Figure/Ground, of painting per se. But I still love painting; I love to do it, I love to look at it.

There was a kind of unified front between, let’s say, Centre Pompidou, October, the New Museum, the Whitney Program, and eventually MoMA that had a lot of institutional power. It wasn’t that women artists were completely excluded; formalism was, painterly essentialism, abstraction and representation that was not appropriated. Appropriation played a big role for me as I started painting: I learned from it; I appropriated political language but not imagery. It was okay for D. Salle to represent women pornographically as long as it was “appropriated”, which supposedly gave him “criticality.”4 There were women painters of course, some of whom were successful at the time, like Susan Rothenberg (1945-2020), or Elizabeth Murray (1940-2007). But the discourse I was addressing was not interested in such “painters’ painters.”

M.T.: Was it possible to identify, as a feminist and painter, with women from the older generation such as Barbara Kruger (b. 1945) or Mary Kelly (b. 1941)? Or were there other models for you?

M.S.: Important early models were Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944), Charlotte Salomon (1917-1943), and by the end of the 1970s, E. Murray, Nancy Spero (1926-2009), Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) and Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010). I admired Ida Applebroog (b. 1929) – who I wrote about for Artforum in 1989 – and Alice Neel (1900-1984). These were and continue to be models. I admired B. Kruger and I recognized the importance of M. Kelly’s work. But the drama of the middle of my career in the 1990s, when I had established a writing practice, is that when I represented the language, it was often appropriated language – political. Yet I was unacknowledged by the theoretical crowd because I was a painter, and accused by feminists who admired M. Kelly’s theoretical basis and methodology of being essentialist, a career-damaging perception at that time. It took almost 15 years for some of the work to begin to be written about in terms I could recognize by writers such as Amelia Jones.

Mira Schor, Time/Spirit (New Red Moon Room), 2022, acrylic, oil, pastel and ink on canvas, 72 x 106 in. (182.88 x 269.24 cm) © Mira Schor. Photo: Aurélien Mole / courtesy Marcelle Alix, Paris.

M.T.: In “The Erotics of Visuality,” you say you are interested in “the return of visual pleasure as a feminist intervention in painting.”5 Is it difficult to have a dialogue with the mostly male history of painting, while remaining feminist?

M.S.: One context for that quote would be the critique of visual pleasure epitomized by Laura Mulvey’s extremely influential essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), a bible of feminist criticism at the time. My models are from the entire history of art, which is mostly male, so it is not difficult to have a dialogue with it. I came to understand that some male artists’ work was considered “feminine” by the art historical hierarchy (see Michelangelo describing the Flemish art of his time as being for monks and women). As a teenager I loved Surrealism to death – despite their personal views on women, at least they were interested in the anima. Many things interest me when I look at a painting: in a Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) every brushstroke is part of a conversation – he says something and I answer.

I have a multi-layered way of experiencing art. It begins with what Walter Benjamin describes as “Fakture,” with the history of painting, and the ideological conditions of representation. When I look at a painting, I’m bilingual: I read the surface and scale, and the story if one is represented.

M.T.: I often found myself torn between, on the one hand, fascination for intelligent writing on materialities from B. Buchloh, for example, and on the other hand, attraction to the visual power of artwork and art history. You asked this question forty years ago…

M.S.: B. Buchloh is brilliant and he does care deeply, however dogmatically. When I wrote “Figure/Ground” (1989),6 young artists told me: “You’ve made me feel that there is a way one can be a painter,” because a lot of them were told by authority figures they respected that they shouldn’t or couldn’t paint. In my writing, I was able to use some of the same references and theoretical support structures as B. Buchloh, while bringing in two other discourses into this argument, that of Klaus Theweleit and of Luce Irigaray. Both were so influential on me.

Mira Schor, Red Moon Room, partial view, Womanhouse, Los Angeles, 1972 © Mira Schor.

Mira Schor, Crazy Lady, 1978, dry pigment, gouache, Japan Gold Size on rice paper, 58 x 23 x 10 in. (147.3 x 71.1 x 25.4 cm) © Mira Schor.

Mira Schor, The Painter’s Studio, 2020, ink, acrylic, and gesso on tracing paper, 119 x 228 inches (302.3 x 579.1 cm) © Mira Schor.

M.T.: You wrote about the pressure on artists to make attention-getting works and also about modest painting. Did you see your gouaches on paper from the 1970s as some explicitly modest contribution to this great tradition of painting?

M.S.: I was aware of the wide issue of the size matter in the history of Western art and of the historical and critical implications – it was a political goal, even. But I was also influenced by my father’s small paintings, by Flemish painting and the predella of early Renaissance altarpieces. In a sense, it was just the work I could do at that time. At Womanhouse, I did a large painting, a mural on three walls of a walk-in closet (4 × 8 ft [120 × 140 cm]) – a walk-in painting. That same year I tried to work on conventional size oil paintings, and it wasn’t right for me at that moment: I was not thinking about oil in my own way. I’ve done a number of works, including War Frieze (1991-1994), that are large, but the components are small; that way, I could make and store the work easily.

In my early twenties, I realized I understood three scales for artwork: what I can hold in my hand; my size as a person; and architectural size. I’ve worked at the scale I can hold in my hand and I learned that you could make a powerful image of that size. Then, in the 1970s, the paper dresses were at the viewer’s scale. In the small paintings, I want the viewer to be drawn to come close to it. In the case of the delicate paper figures, I was interested in the relation to the male viewer: confronted by a delicate, feminine form in their space, they received it as aggressive. Lately, I was able to work at an architectural scale on a few works, including an 18-foot-wide (5.5-m-wide) painting on tracing paper. The fragility is ridiculous, like a giant butterfly wing. It is my version of Gustave Courbet’s L’Atelier du peintre (1884-1885).

Mira Schor, The Jewish Daughter, 1985, oil on canvas, 112 x 12 in. (284.5 x 30.5 cm) © Mira Schor.

Ilya Schor, Torah Crown, early 1950s, silver (this work was most likely destroyed in a synagogue fire in the 1950s).

M.T.: Your parents, Ilya Schor (1904-1961) and Resia Schor (1910-2006) were both artists who migrated from Poland to France and then fled France to New York to escape the Holocaust. You were born in the United States. How is this mixed culture, which shows in The Jewish Daughter (1985) – where an abstracted female figure is crowned by a representation of one of your father’s silver Torah Crowns – also present in the rest of your work? Was your parents’ work important to you?

M.S.: My father’s work often contained representations of Hebrew text. I don’t read Hebrew, so I could only experience the text as form or as the idea of writing and learning. I painted The Jewish Daughter just as I was finishing the D. Salle essay. I’d immersed myself in the ideology that promoted appropriation as the only way that one could legitimately produce political imagery without falling into all the traps of history and essentialism. I thought, well, I’ll appropriate something, one of my father’s Torah Crowns,7 which is not something I see ironically, but something I love and think was a masterpiece – it was destroyed in a synagogue fire.

I remember my father working in his workshop at home, looking at the movements of his paintbrush or his engraving mark. I took that in deeply. His career came first, chronologically and in the importance in our family, but also in the world because he counted as an authentic voice of the spirit of Eastern European Jewry destroyed by the Holocaust. I was influenced by him, his work and his presence. When he died, my mother, who was an abstract painter, was only 50 years old. She had two children and had to make a living, so she decided to finish some of the work he had left unfinished on his worktable. She’d never done work in that medium before. And suddenly, she began to do beautiful jewelry in her own style, completely sculptural, abstract. I admired her work and she valued my opinion, even as a teenager. My father was a delicate artist, with a light hand, very skilled, while my mother’s approach was more muscular and bolder. She worked a lot over the kitchen stove where she had a gas set-up to solder her larger works in silver. She would have goggles on, and her face completely covered in soot. She made a living, she exhibited, and her work was written about. It was mainly considered “craft,” but I think it was strong and unique as art.

Students often ask questions about the value of art, the political interest, or the value of being an artist if you’re not famous. It’s not that I think art can change the world, but it certainly is my world. It’s helped me live. But it is just the family business at the same time; art is a normal activity.

Mira Schor, Wet: On Painting, Feminism, and Art Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997), p. VII.

2

“I would like to put forward the notion of ‘modest painting.’ It won’t put itself forward, because it is inherently resistant to the self-commodification actively encouraged by contemporary culture.” Mira Schor, “Modest Painting,” Art Issues (January-February 2001): p. 18.

3

Mira Schor, “Appropriated Sexuality” (1986), in M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism, eds. Susan Bee and Mira Schor (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), pp. 24-36.

4

Ibid.

5

Mira Schor, “The Erotics of Visuality” (1992), in Wet: On Painting, p. 165.

6

“Figure/Ground” (1989), in ibid., pp. 144-155.

7

Mira Schor, “Ilya Schor and Resia Schor: Refuge as Transformation,” Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation, June 8, 2022.

Matylda Taszycka is Head of Research Programmes at AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, where she leads initiatives and directs research on women artists from the 19th and 20th centuries. Among other things, she is in charge of the planning of conferences in partnership with museums and universities, as well as the coordination of the AWARE Prize for Women Artists. A graduate from the École du Louvre in Paris, she worked at the Monnaie de Paris, before joining the Polish Institute of Paris as Head of Visual Arts. She is also an independent curator and art critic.

The interview was transcribed by Éléonore Besse.

Matylda Taszycka, "Mira Schor: The Language of Painting." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibition Magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/mira-schor-le-langage-de-la-peinture/. Accessed 29 January 2026