Focus

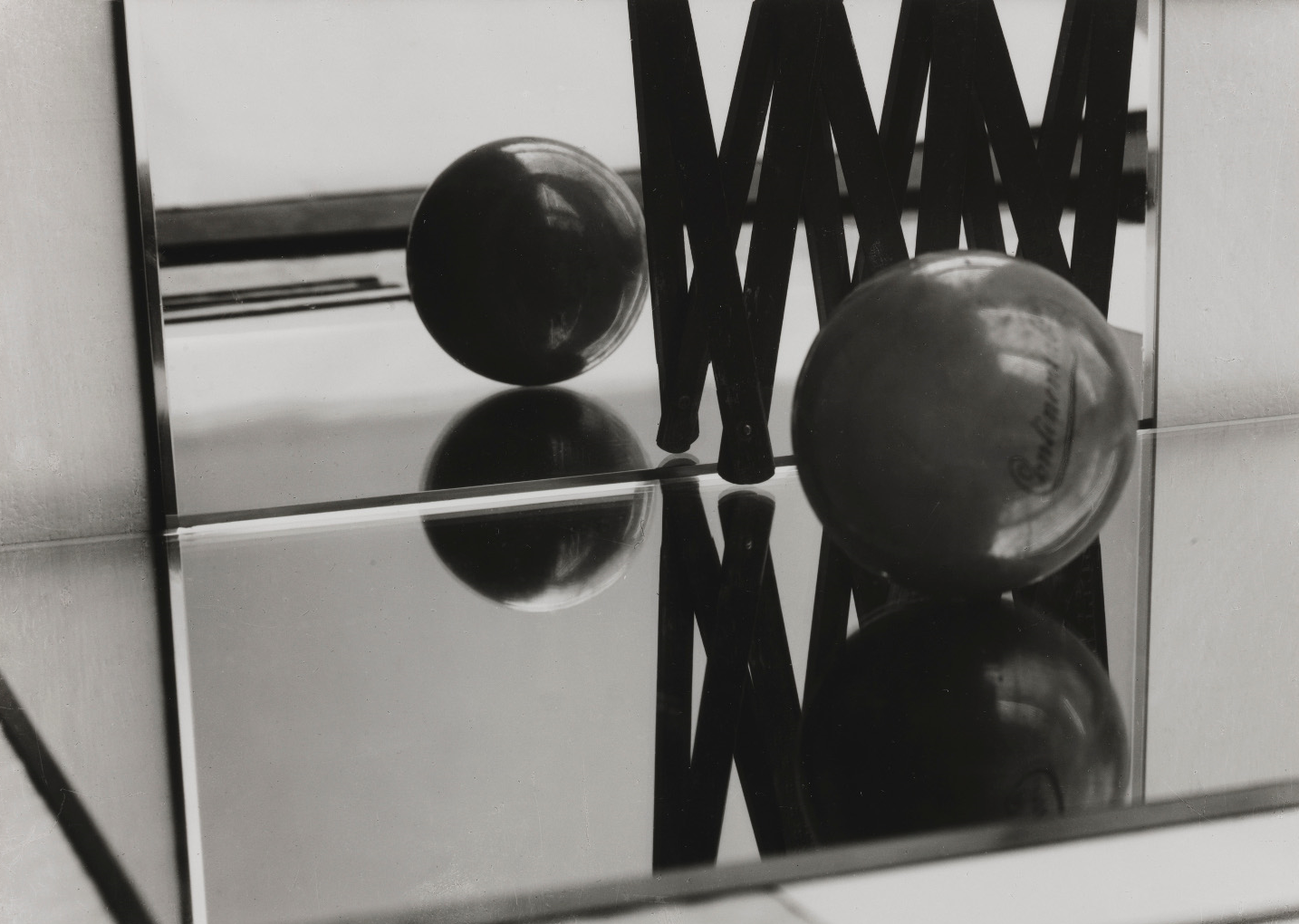

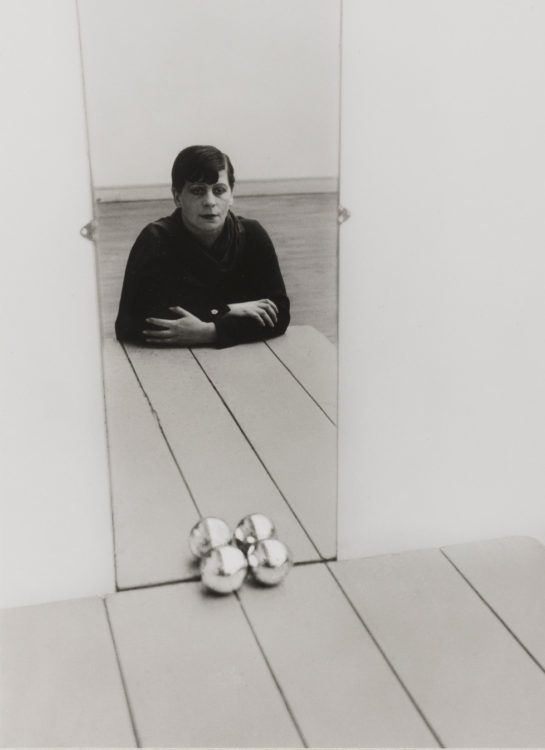

Florence Henri, Komposition II, 1928, silver print, 17.2 x 23.9 cm, © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genua/Italien, © Bahaus-Archiv Berlin

In the wake of the First World War many women took up photography. Paris, centre of the avant-gardes, became a place of encounter and exchange for artists from everywhere.

Free of a masculine tradition and attractive, photography rapidly became a medium of choice for women. They seized the stylistic and theoretical repertoire of the image, contributed to the emergence of modernity and participated in artistic movements such as Surrealism, the New Objectivity and the New Vision. The development of the illustrated press opened up professional opportunities for them; the practice of image making was a means of ensuring a regular income and making themselves known.

Artists investigated various fields of photography. Berenice Abbott (1898-1991) and Rogi André (1905-1970) presented themselves through their portraits of artists and intellectuals. Florence Henri (1893-1982) made advertisements, notably for Lanvin perfumes. Others worked on the representation of the nude. Ergy Landau (1896-1967) depicted female bodies, while Laure Albin Guillot (1879-1962) was one of the first to capture the image of an undressed male – a taboo subject outside of naturist or sporting frameworks. The medium also became a way of mastering staging. In her self-portraits, Claude Cahun (1894-1954) blurred the notions of identity through masquerade. F. Henri used mirrors as tools to distance gender assignments and reinvent an aesthetic construction of the representation of women.

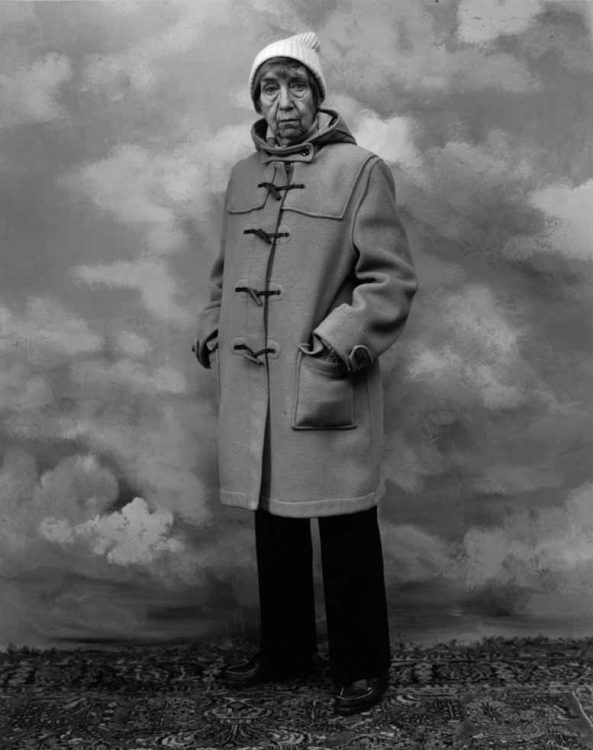

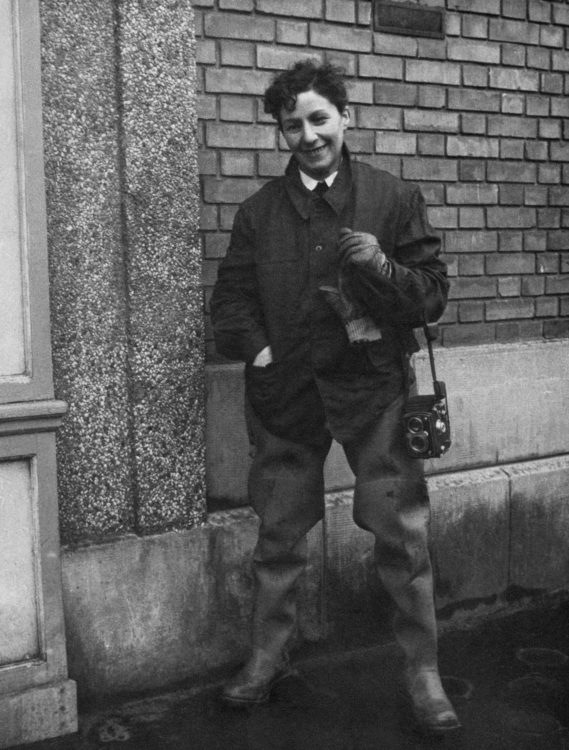

Female photographers were not confined to working indoors; they went outside to conquer male-occupied territories such as public and political space, and the emerging markets of photojournalism and documentary photography. Marianne Breslauer (1909-2001) immortalised the French capital, showing her female contemporaries in the streets, cigarette in hand. Lisette Model (1901-1983) documented the bourgeoise society and interrogated social norms. Ilse Bing (1899-1998) and Germaine Krull (1897-1995) appropriated symbols of modernity typically associated with virility: automobiles, industrial architecture and geometric landscapes. Finally, Lee Miller (1907-1977) annexed men’s stronghold in war reporting.

Women photographers in Paris formed networks for recognition and apprenticeship. German photographer Gertrude Fehr (1895-1996) opened a photography school in 1934. E. Landau offered private training courses. Gradually, they were given a key role in the theoretical development of the medium and participated in its institutionalisation. Gisèle Freund (1908-2000) defended the first thesis on photography in France in 1936. L. Albin-Guillot, president of the Society of Photographic Artists, organised exhibitions where women took their place.

The importance of female photographers in Paris during the interwar period is undeniable. So how can we explain the oblivion into which many of them have plunged? Critics of the time associated their production with a feminine specificity, thus hierarchising it in relation to so-called “universal” creation, considering that if women were able to compete with men, it was thanks to the camera that served as their ally. Indeed, in her report on the 1936

Exposition Internationale de la Photographie Contemporaine (International exhibition of contemporary photography), Hélène Gordon wrote, “In photography … women have an effective and, above all, objective collaborator: the camera.” Considering the tool as the receiver of creative capacity and consequently devaluing the practice of women is yet another way of erasing their contributions.

1898 — 1991 | United States

Berenice Abbott

1879 — 1962 | France

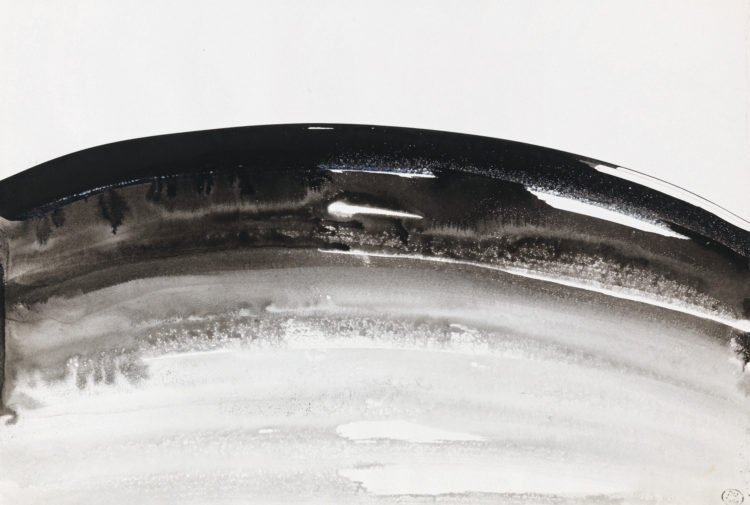

Laure Albin Guillot

1907 — 1997 | France

Dora Maar

1905 — Hungary | 1970 — France

Rogi André

1901 — Austria | 1983 — United States

Lisette Model

1899 — Germany | 1998 — United States

Ilse Bing

1909 — Germany | 2001 — Switzerland

Marianne Breslauer

1894 — France | 1954 — Jersey

Claude Cahun

1902 — 2004 | France

Denise Colomb

1908 — Germany | 2000 — France

Gisèle Freund

1893 — United States | 1982 — France

Florence Henri

1897 — Poland | 1985 — Germany

Germaine Krull

1898 — 1933 | Germany

Aenne Biermann

1896 — Hungary | 1967 — France

Ergy Landau

1907 — United States | 1977 — United Kingdom

Lee Miller

1924 — Switzerland | 2021 — France

Sabine Weiss

1914 — United Kingdom | 2000 — United States

Constance Stuart Larrabee

1912 — German Empire | 2000 — Germany

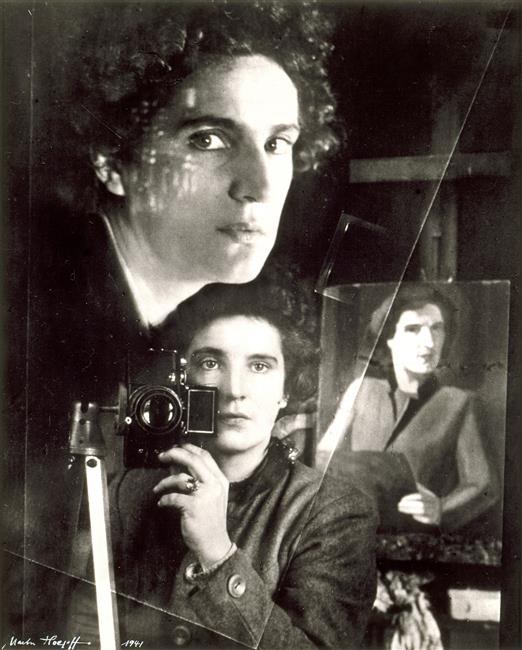

Marta Hoepffner

1910 — 1981 | Germany

Elsa Thiemann

1873 — France | 1961 — Switzerland

Céline Gracieuse Laguarde

1947 | Japan

Miyako Ishiuchi

1928 — 2019 | Japan