Focus

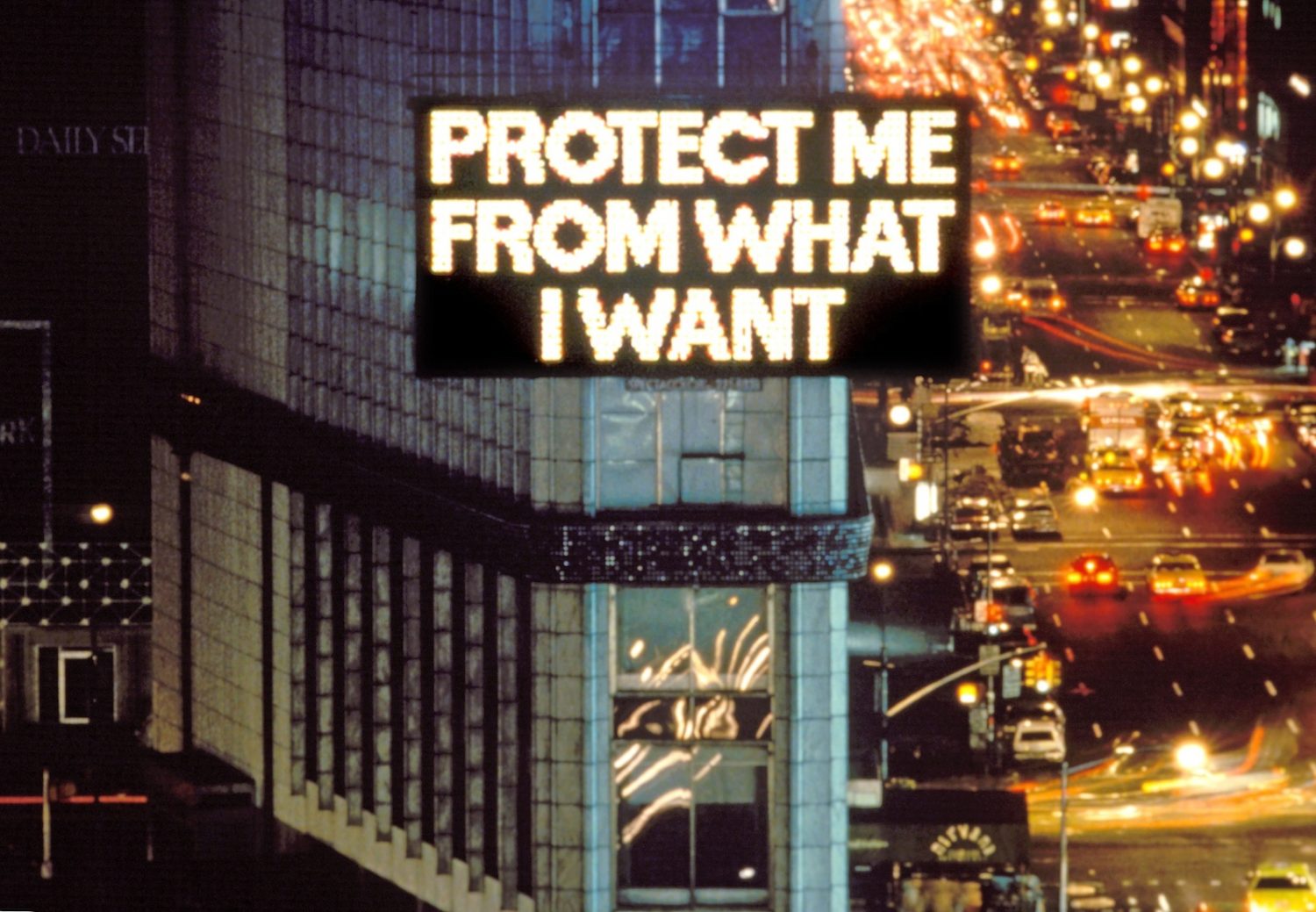

Jenny Holzer, Protect me from what I want, from Survival (1983–85), 1985, electronic panel, 6.1 x 12.2 m, Times Square, New York, © Photo: John Marchael, © Jenny Holzer, © ADAGP, Paris

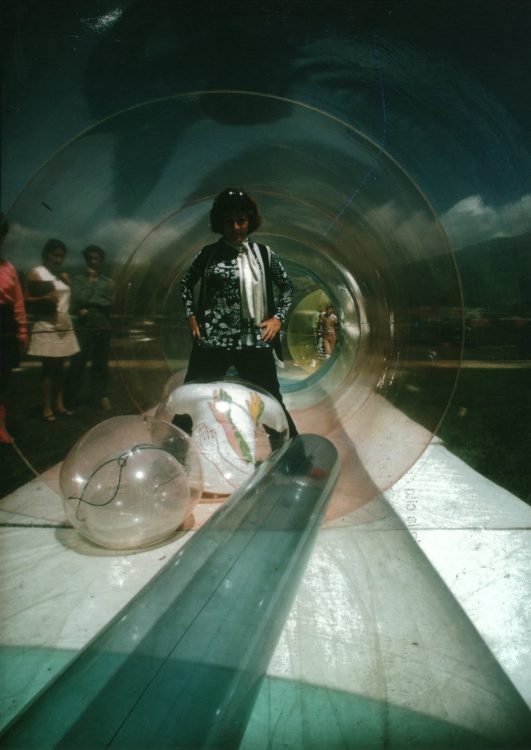

In 1967, Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002) built her first Nana-Maison and started to occupy public places with round, colourful female figures, restoring their place to women creators in towns which had mainly been occupied by men. “The flourishing of her colossal urban art corresponds in the same way to the arrival on the public scene of the women’s rights protest movement of which she forged a plastic equivalent,” explained art historian, Fabienne Dumont. At a time when the fields of sculpture and architecture were considered as masculine, women artists recaptured public places by installing monumental works, refusing the domesticity to which they were confined. It was a way of showing that women are capable of the same achievements as men: “I obey my pressing need to show that a woman can work on monumental scale,” said Niki de Saint Phalle regarding the creation of her sculpture park, Le Jardin des Tarots (1978-1998).

Feminist artists who create monumental works for public places wished to offer a more democratic art in tune with inhabitants. To do this, some first took over the streets in a non-conventional fashion by directly addressing passersby. They flooded towns with their messages: In 1978, using 54 NI panels, Tania Mouraud (b. 1942) indicated all the places in Paris from which women were excluded, and as of 1977, Jenny Holzer (b. 1950) showcased her Truismes. Others used monumental advertising posters: in 1989, the Guerrilla Girls asked: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”, and Barbara Kruger (b. 1945) used the phrase: “Your body is a battleground” to protect abortion rights in the United States, a slogan that French urban artist, Miss.Tic, would reuse in 2000 in Paris.

Other artists with feminist preoccupations have had works commissioned by government bodies, for which they have produced monumental sculptures: Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely (1925-1991) in 1983 with the Fontaine Stravinsky in Paris; Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) in 2005 with her spiders called Maman; Monica Bonvicini (b. 1965), in 2010, with She Lies, a floating structure opposite the Oslo Opera, Joana Vasconcelos (b. 1971)in 2018 with Cœur de Paris at Porte de Clignancourt, on tramway line T3 in Paris.

Feminist artists also give written and visual portrayals of the demands heard in the demonstrations of the 1960s and 1970s. Viewers are thus confronted with works by women which are more and more imposing and more and more perennial. These women creators of an inclusive town thus give women a right to express themselves in public.

1950 | United States

Jenny Holzer

1930 — France | 2002 — United States

Niki de Saint Phalle

1942 | France

Tania Mouraud

1971 | France

Joana Vasconcelos

1985 | United States

Guerrilla Girls

1965 | Italy

Monica Bonvicini

1945 | United States

Barbara Kruger

1939 — 2015 | United States

Rosemarie Castoro

1932 | Canada

Dorothea Rockburne

1859 — 1926 | France

Blanche Adèle Moria

1967 | Senegal

Fatou Kiné Diakhaté

1967 | United States

Simone Leigh

1942 — 2008 | Argentina

Mildred Burton

1958 | Colombia

Doris Salcedo

1957 | France

Élisabeth Ballet

1961 | United States

Zoe Leonard

1963 | United Kingdom

Rachel Whiteread

1875 — 1942 | United States

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

1929 — Poland | 1999 — France

Lea Lublin

1955 | Canada

Geneviève Cadieux

1948 | Lithuania

Esther Shalev-Gerz

1942 | United States

Joyce Kozloff

1949 | Turkey

Ayşe Erkmen

1964 | Martinique, France

Valérie John

1945 | United States

Jean LaMarr

1939 — 1988 | Japan

Sayako Kishimoto

1957 | Canada

Dominique Blain

1934 — Germany | 2021 — France

Irmgard Sigg

1973 | Germany

Nadia Lichtig

1945 — 2022 | Argentina

Graciela Gutiérrez Marx

1973 | France

Emmanuelle Lainé

1934 | Belgium

Marianne Berenhaut

1945 | United Kingdom

Maggi Hambling

1973 | United States

Erika Vogt

1970 | United Kingdom

Jenny Saville

1972 | Japan

Chiharu Shiota

1940 — 2021 | Zimbabwe

Helen Lieros

? |

Céline Condorelli

1906 — Iraq | 1986 — Lebanon

Mouazzaz Rawda

1948 | Chile

Cecilia Vicuña

1935 | Luxembourg

Berthe Lutgen

1946 | USA

Lita Albuquerque

1929 — 2014 | Japan