Focus

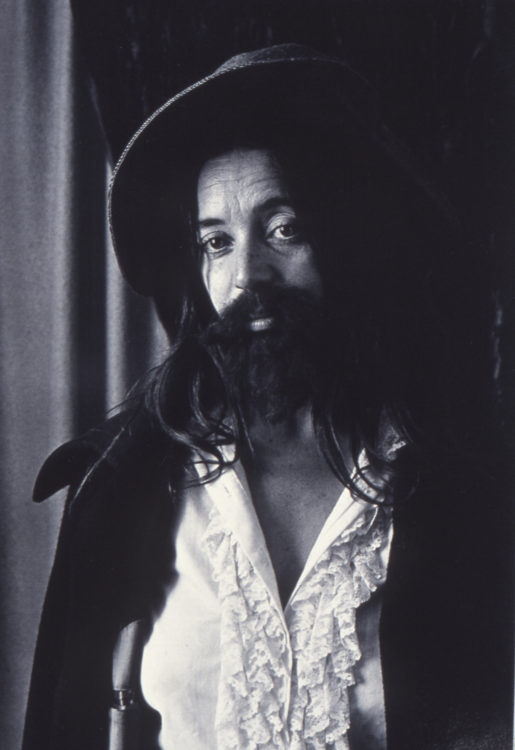

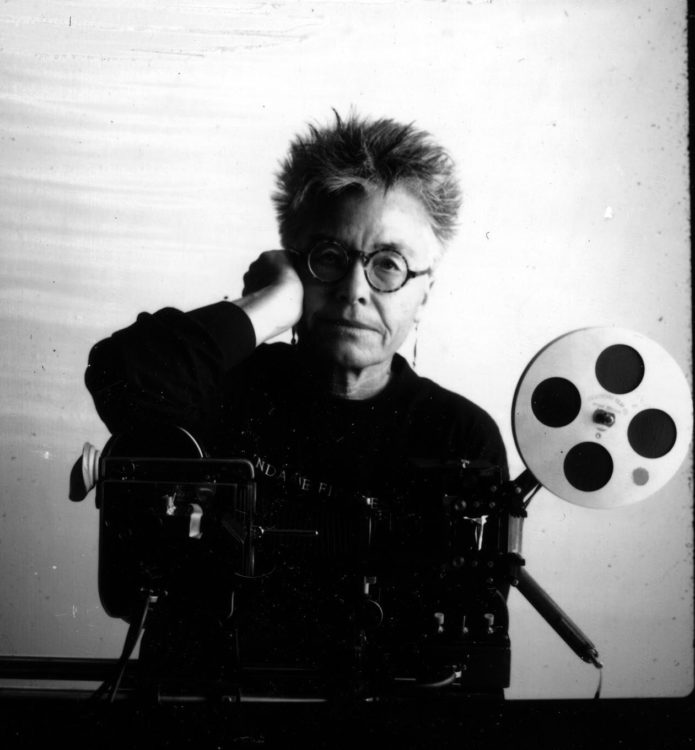

Ulrike Rosenbach, Die Einsame Spaziergängerin [The lonely stroller], 1979, performance, photograph, © ADAGP, Paris

Before becoming a full-fledged medium, video was intrinsically linked to television. It wasn’t until the 1960s—most notably with the launch of the Sony Portapak in 1967, the first portable video recorder—that video became independent of television shows and sets. This development made it possible to film anywhere, and artists began to embrace the technique in their practices.

The first uses of the electronic image as an artistic medium appeared within the Fluxus movement. In March 1963, Nam June Paik (1932–2006) created a distorted television image by placing a magnet close to the cathode-ray tube. This work is remembered as the birth of video art.

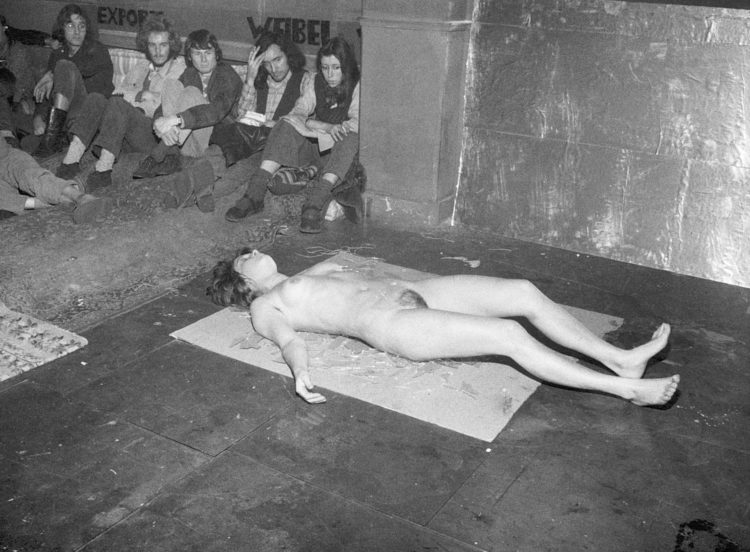

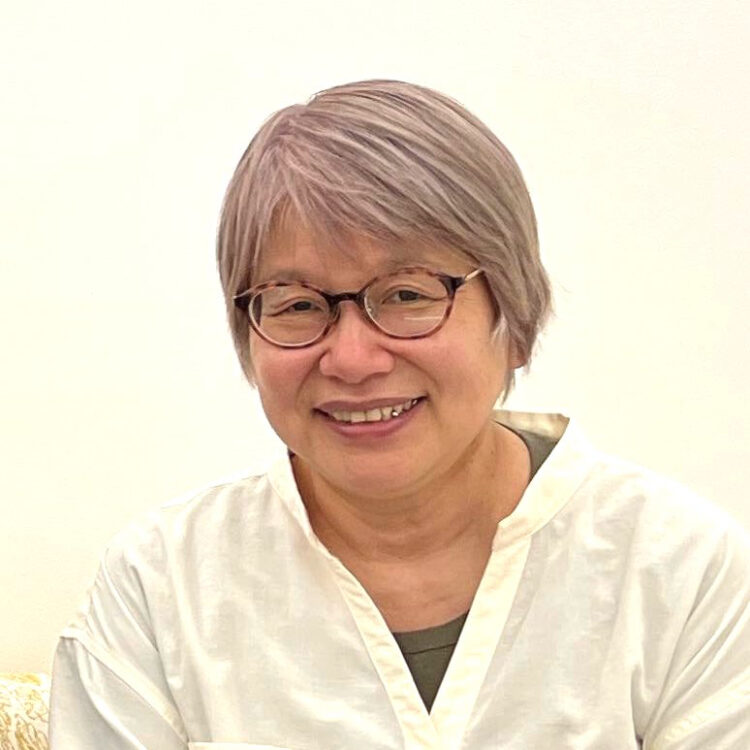

Since then, many women artists have adopted the medium and contributed to its development. VALIE EXPORT (b. 1940) infiltrated the world of television in her 1971 work Facing a Family, questioning the relationship between watching and being watched. Ulrike Rosenbach (b. 1943) was among the first video artists to create closed-circuit pieces, simultaneously filming and projecting images. Performers Marina Abramović (b. 1946) and Leda Papaconstantinou (b. 1945) began documenting their actions in the late 1960s, transforming the relationship between their work and the ephemeral.

From 1972 to 1980, the Women’s Video Festival took place at The Kitchen in New York, spotlighting underrepresented video artists such as Japanese artist Shigeko Kubota (1937–2015), a member of the Fluxus group.

Video art opened up a new universe of experimentation: images could be manipulated or erased, with or without archiving. Nan Hoover (1931–2008) explored the possibilities of transparency, creating works that hovered between painting and film. Dóra Maurer (b. 1937) has worked with repetition and variation, producing complex compositions of image and sound.

As both a creative tool and a means of protest, video became a way to challenge the dominant artistic movements of the 1960s. Joan Jonas (b. 1936) approached her work with an introspective, narrative, and symbolic style, breaking away from minimal art. In Up and Including Her Limits (1973), Carolee Schneemann (b. 1938) drew by following the movements of her body, suspended during a performance that was filmed and broadcast on monitors. In this work, the artist evoked a gesture akin to action painting but distanced herself from it by treating the resulting drawings as secondary, raising questions about the relationship between creative process and final work.

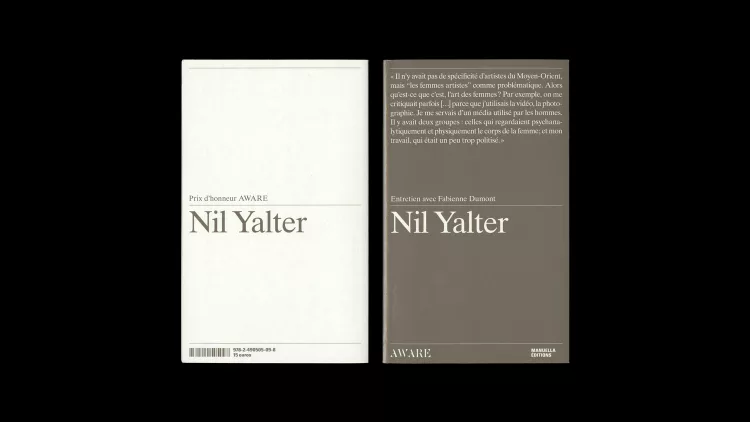

Like photography, the video camera has become a privileged medium for exposing and denouncing oppression. Martine Barrat (b. 1937) directed a series of videos on the lives of gang members in the South Bronx. In the installation La Roquette, Prisons de femmes, Nil Yalter (b. 1938), in collaboration with Judy Blum (b. 1943) and Nicole Croiset, denounced prison conditions. Howardena Pindell (b. 1943) addresses issues of race and gender, while Anna Maria Maiolino (b. 1942) condemns the censorship of women in Brazil. The filmmaking duo Maria Klonaris (1947–2014) and Katerina Thomadaki (b. 1947) theorized what they called “corporeal cinema,” making the female body and identity central to visual and political exploration. Serving various militant causes, video became an instrument for subverting patriarchy. As early as 1976, the French video collective Les Insoumuses declared in their video Maso et Miso vont en bateau: “No television image can embody us; it is with video that we will tell our own stories.”

Video has been extensively embraced by women artists. Numerous writings continue to highlight their place in art history and the connections between this medium and political as well as feminist struggles. The joint publications Black Women Film and Video Artists (1998), edited by Jacqueline Bobo, and Women Artists, Feminism and the Moving Image: Contexts and Practices (2019), edited by Lucy Reynolds, are significant milestones in the study of women video artists.

1938 | Egypt

Nil Yalter

1939 — 2019 | United States

Carolee Schneemann

1936 | United States

Joan Jonas

1943 | United States

Howardena Pindell

1948 | United States

Adrian Piper

1946 | Serbia

Marina Abramović

1948 — Cuba | 1985 — United States

Ana Mendieta

1943 | Germany

Ulrike Rosenbach

1940 | Austria

VALIE EXPORT

1935 — 2022 | Brazil

Sonia Andrade

1935 | UNITED STATES

Eleanor Antin

1937 | Algeria

Martine Barrat

1933 | Brazil

Anna Bella Geiger

1931 — United States | 2008 — Germany

Nan Hoover

1949 | Croatia

Sanja Iveković

1967 | Greece

Klonaris/Thomadaki

1937 — Japan | 2015 — United States

Shigeko Kubota

1942 | Italy

Anna Maria Maiolino

1937 — 2026 | Hungary

Dóra Maurer

1933 | Japan

Yoko Ono

1947 | France

ORLAN

1945 | Greece

Leda Papaconstantinou

1927 — 2004 | Brazil

Lygia Pape

1945 | Poland

Ewa Partum

1943 | United States

Martha Rosler

1928 — Belgium | 2019 — France

Agnès Varda

1962 | Russia

Olga Chernysheva

1936 | United States

Barbara Kasten

1948 — New Zealand | 2014 — England

Alexis Hunter

1927 — 2019 | United States

Lillian Schwartz

1909 — 1970 | United States

Marie Menken

1962 | Switzerland

Pipilotti Rist

1950 — Belgium | 2015 — France

Chantal Akerman

1939 — 2019 | United States

Barbara Hammer

1972 — Switzerland | 1963 — Germany

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz

1954 | Taiwan

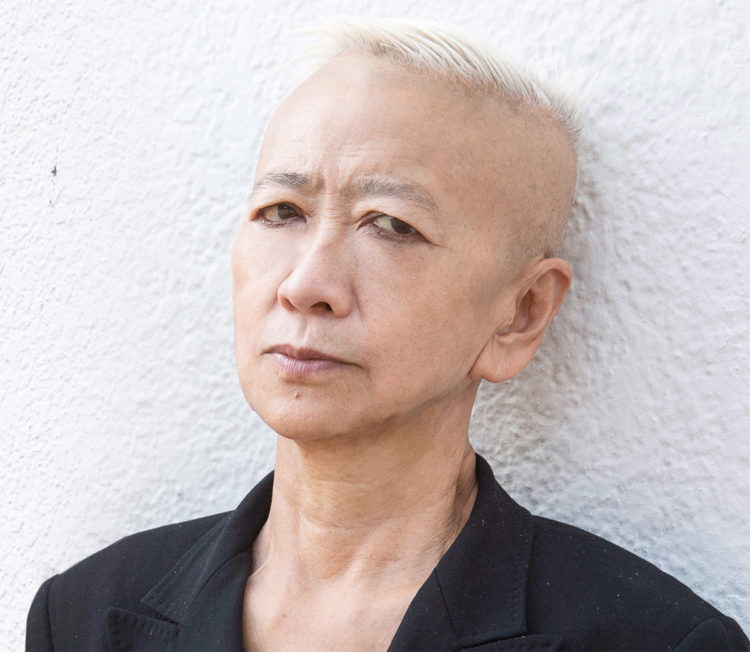

Shu Lea Cheang

1970 | Turkey

CANAN (Şenol)

1934 | United-states

Yvonne Rainer

1962 | Turkey

Şükran Moral

1992 | Spain

Cabello/Carceller

1940 — 2015 | Spain

Elena Asins

1960 | United States

Lorna Simpson

1965 | Australia

Julie Gough

1961 | Australia

Lynette Wallworth

1956 | Spain

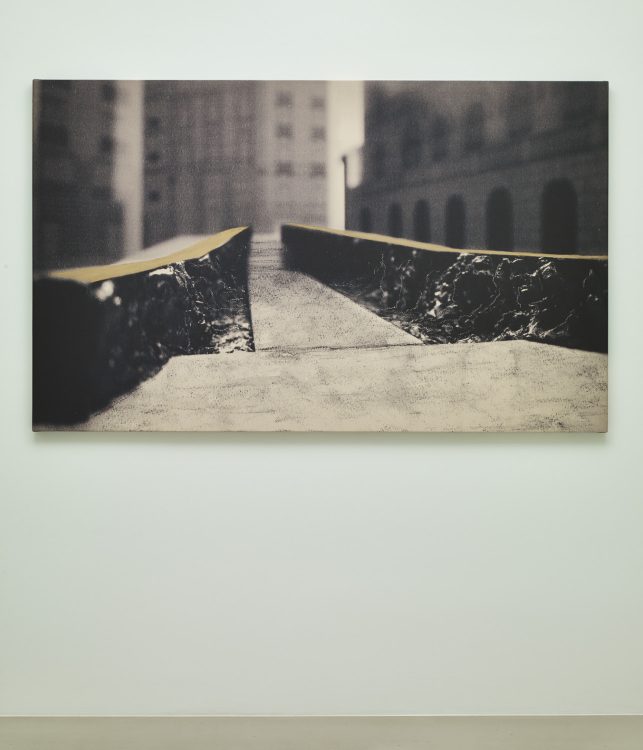

Cristina Iglesias

1951 — 2021 | Japan

Tāri Itō

1963 | France

Zineb Sedira

1959 | Japan

Yoshiko Shimada

1940 — 1993 | United States

Hannah Wilke

1944 | Morocco

Joëlle de La Casinière

1969 | Israel

Nira Pereg

1969 | Hong Kong

MAN Phoebe Ching Ying

1970 | Austria

Elke Silvia Krystufek

1959 | Estonia

Kai Kaljo

1947 | Poland

Zofia Kulik

1937 — 2022 | Poland

Natalia LL

1930 — 1998 | Canada

Joyce Wieland

1946 | Hungary

Orshi Drozdik

1941 | Pérou

Rose Lowder

1954 | Israel

Michal Heiman

1972 | United States

Maha Maamoun

1966 | Netherlands

Patricia Kaersenhout

1972 | Israel

Raida Adon

1951 — South Korea | 1982 — United States

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

1961 | China

PAU Ellen

1959 | Canada

Dana Claxton

1969 | Russia

Louisa Babari

1973 | Vietnam

Trinh Thi Nguyen

1973 | United Kingdom

Rosalind Nashashibi

1940 | Japan

Mako Idemitsu

1960 | Myanmar

Phyu Mon

1962 — 2023 | Taiwan

HOU Lulu Shur-tzy

1973 | France

Agnès Geoffray

1973 | France

Katia Kameli

1973 | France

Maïder Fortuné

1973 | Luxembourg

Su-Mei Tse

1967 | Japan

Miwa Yanagi

1973 | France

Mathilde Rosier

1957 | Thaïlande

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook

1973 | Brazil

Clarissa Tossin

1973 | Bulgaria

Rada Boukova

1946 — 2025 | United States

Dara Birnbaum

1970 | Netherlands

Deborah Jack

1973 | United States

Erika Vogt

1967 | Nigeria

Fatimah Tuggar

1971 | France

Yto Barrada

1941 | United States

Lynn Hershman Leeson

1967 | Spain

Tere Recarens

1965 | Spain

Mabel Palacín

1974 | Denmark

Pia Rönicke

1974 | France

documentation céline duval (doc-cd)

1943 | France

Anne Deguelle

1963 | Spain

Eulàlia Valldosera

1939 | Brazil

Regina Silveira

1956 | Brazil

Simone Michelin

1948 | Republic of Korea

Okhi Han

1965 — 1991 | Mexico

Elvira Palafox Herrán

1974 | Germany

Ulla von Brandenburg

1974 | France

Marie Voignier

1970 | Hungary

Eszter Salamon

1948 — Lebanon | 2019 — France

Jocelyne Saab

1971 | Uzbekistan

Anna Ivanova

1958 | United Kingdom

Suzanne Treister

1956 | Syria

Hala Alabdalla

1969 | Myanmar

Chaw Ei Thein

1948 — 2017 | Pakistan

Lala Rukh

1971 | Ukraine

Kristina Solomoukha

1930 — 2013 | Serbia (Yugoslavia)

Bogdanka Poznanović

1954 | Brazil