Focus

Charley Toorop, Still life with skull, 1929, oil on panel, Kroller-Muller Museum, Otterlo, © ADAGP, Paris

Still life had its golden age in the 17th century, notably in northern Europe with the paintings of Pieter Claesz (c. 1597-1660) as well as those of Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750). These works do not show human figures but rather dishes, fruits, vegetables, objects and flowers, often symbolic vanitas. At times considered simply as an exercise, the genre remained minor in the Western pictorial tradition in the face of history painting and portraiture. Having fallen into oblivion in the 19th century, the still life is often associated with women’s artistic practice illustrating the lack of critical consideration for female creators. The association between femininity and floral painting was the fruit of activity in porcelain and ceramic workshops as well as that of textile manufacturers. This was the case for Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) in the Omega Workshops she created with the Bloomsbury Group in 1913, where she designed plant motifs for English interiors.

The still life’s ambiguity is clear throughout the careers of the artists. Sometimes as a practical exercise, women artists made their mark with still lifes before turning to practices that better suited them. Émilie Charmy (1878-1974) painted still lifes, but it was in her brothel scenes and portraits of the author Colette (1873-1954) that she found her own means of expression and established her work’s originality. Both Betty Goodwin (1923-2008) in Romania, and Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944) in the United States, began their apprenticeships with this exercise, not aiming at audacity and creativity but rather the accuracy of line and study. This idea is also confirmed in contemporary art with Carole Benzaken (b. 1964), for example, who began by representing tulips as a means to question the meaning of the image and the pictorial tradition.

Yet still life is also a genre in and of itself. After the war Geneviève Asse (b. 1923) created still lifes that she limited to only three colours – white, black and ochre. This almost monochromatic approach allowed her to access a greater freedom and amplitude in her way of making. This pictorial genre is found in aesthetic research of artistic movements. As such, Maria Blanchard (1881-1932) and Valéria Dénes (1877-1915) realised still lifes in the cubist style while Charley Toorop (1891-1955) worked in a more realistic style. In her work Frances Hodgkins (1869-1947) confronted still lifes with landscapes. This modernity also has an echo in photographic practices. Aenne Biermann (1898-1933) fixed still lifes to film in strict compositions and structures before reworking them using editing techniques. In Japan, where flower painting is a traditional art, Fujio Yoshida (1887-1987) appropriated floral motifs and worked them to the point of organic abstraction. She realised these forms with different techniques, including woodblocks, engravings and oil painting. For certain female artists in the West, these representations became a means of expression that they appropriated to change their meaning, as did Juliette Roche (1884-1982) by inserting strong political messages into her works.

The still life reinvented itself in performance and installation as seen in the work of the Czech artist Jana Sterback (b. 1953) and Gloria Friedmann (b. 1950) from Germany, where it is nourished by current issues relating to ecology and the environment.

1879 — 1961 | United Kingdom

Vanessa Bell

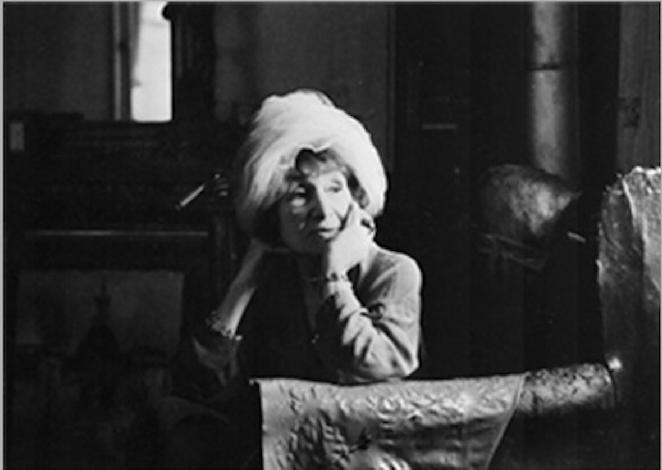

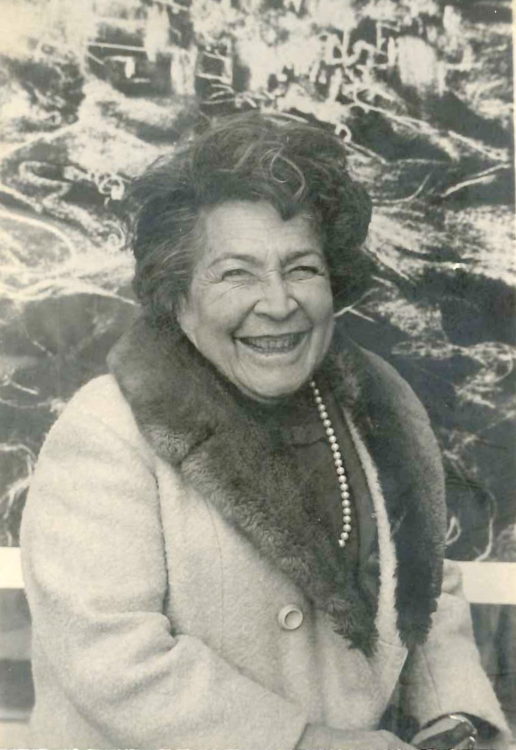

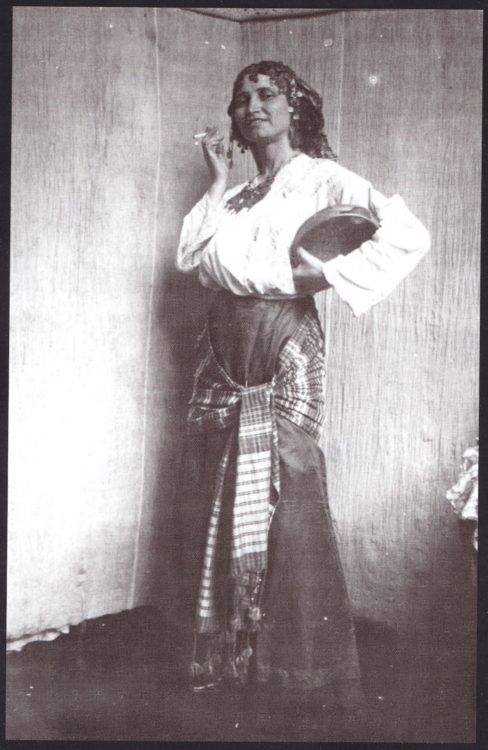

1878 — 1974 | France

Émilie Charmy

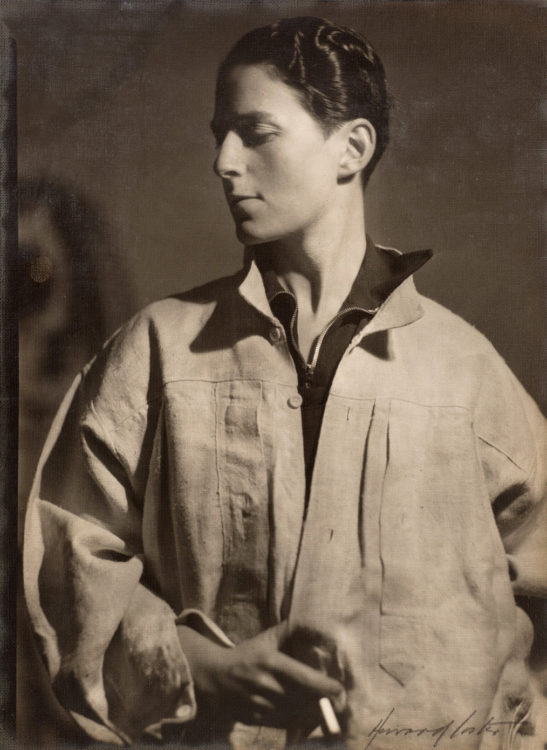

1869 — New Zealand | 1947 — United Kingdom

Frances Hodgkins

1923 — 2008 | Canada

Betty Goodwin

1871 — 1944 | United States

Florine Stettheimer

1881 — Spain | 1932 — France

María Blanchard

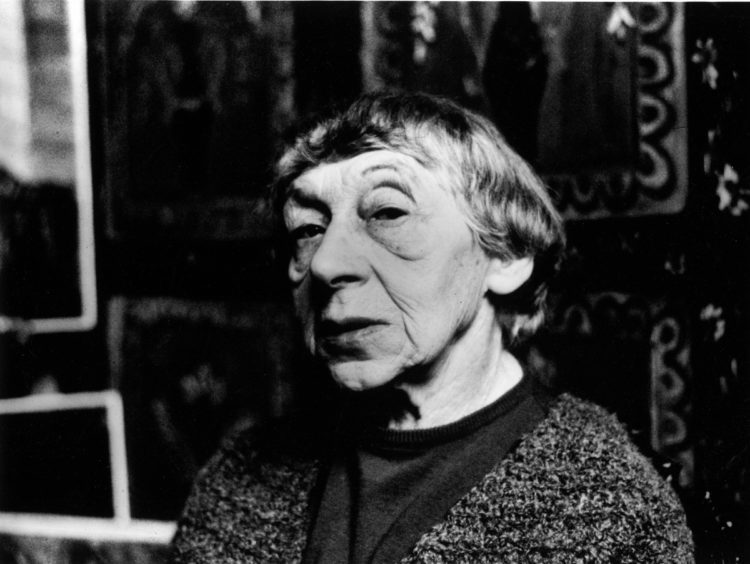

1891 — Netherlands | 1955 — Norway

Charley Toorop

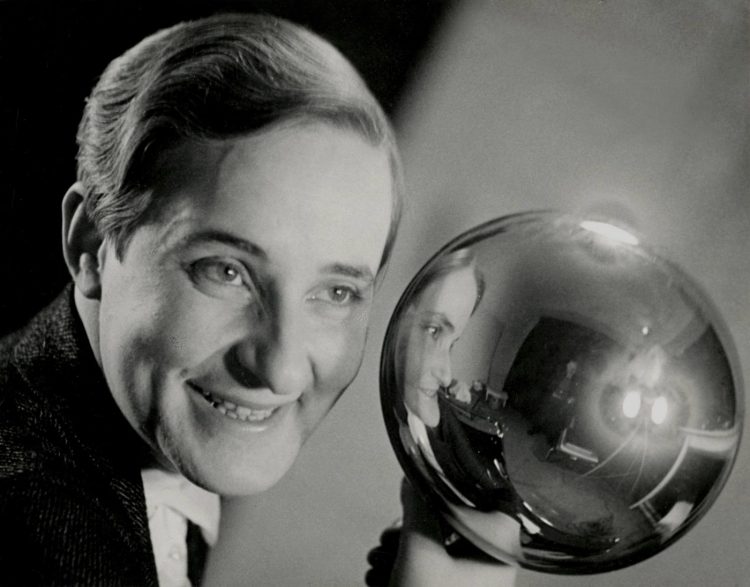

1898 — 1933 | Germany

Aenne Biermann

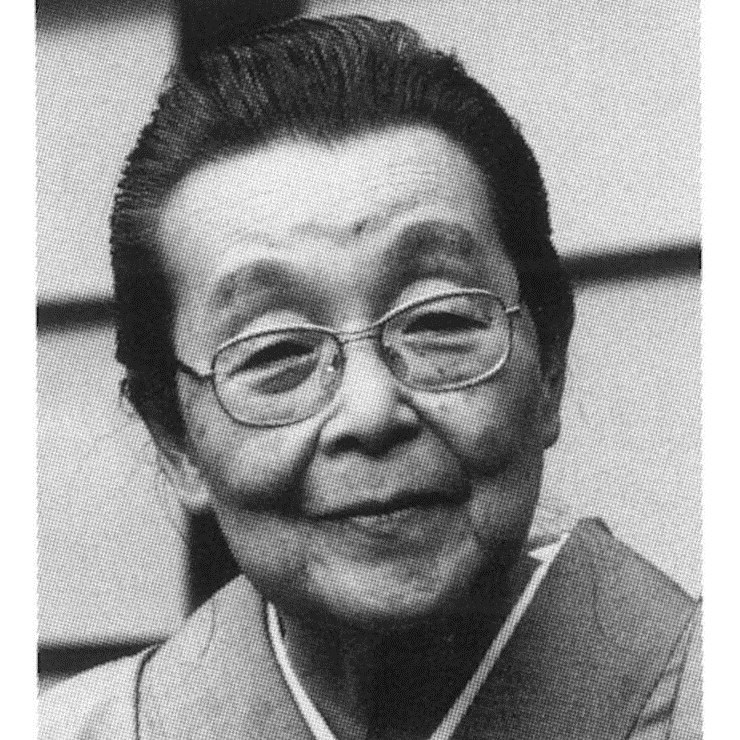

1887 — 1987 | Japan

Fujio Yoshida

1893 — United States | 1982 — France

Florence Henri

1885 — Australia | 1951 — France

Anne Dangar

1877 — 1915 | Hungary

Valéria Dénes

1898 — Russian Empire (today Ukraine) | 1984 — Soviet Union

Maria Siniakova

1895 — Poland | 1975 — France

Alice Halicka

1950 | Germany

Gloria Friedmann

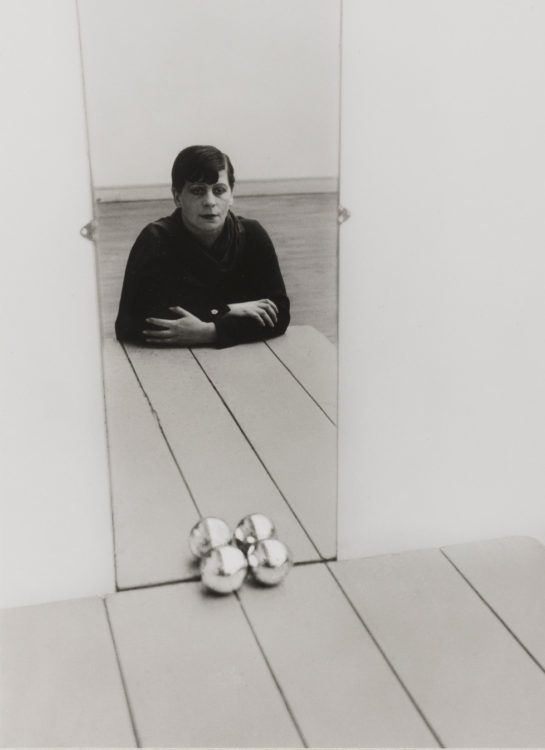

1953 | Czech Republic

Jana Sterbak

1964 | France

Carole Benzaken

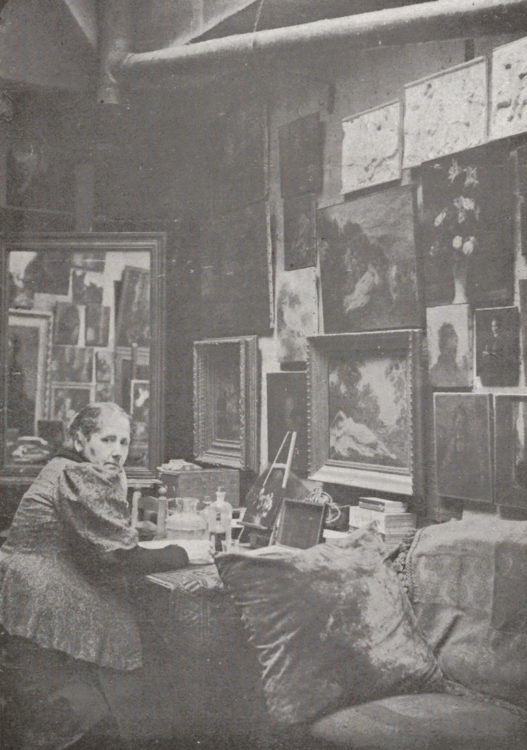

1840 — 1926 | France

Victoria Dubourg

1895 — Samoa | 1984 — New Zealand

Teuane Tibbo

1827 — 1888 | France

Éléonore Escallier

1856 — 1942 | United States

Anna Elizabeth Klumpke

1900 — 1981 | Bosnia and Herzegovina

Mileva Todorović

1894 — Moravia (now Czech Republic) | 1980 — Israel

Anna Ticho

1845 — 1928 | France

Madeleine Lemaire (Jeanne Magdelaine Lemaire, dite)

1895 — 1978 | United Kingdom

Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein, dite)

1906 — 1958 | China

QIU Ti (Schudy)

1905 — 1999 | Japan

Setsuko Migishi

1964 | France

Françoise Pétrovitch

1845 — 1932 | Norway

Harriet Backer

1895 — 2000 | Japan

Yuki Ogura

1791 — 1878 | United States

Anna Claypoole Peale

1795 — 1882 | United States

Margaretta Angelica Peale

1800 — 1885 | United States

Sarah Miriam Peale

1709 — Netherlands | 1772 — United Kingdom

Cornelia van der Mijn

1700 — Netherlands | 1777 — United Kingdom

Agatha van der Mijn

1664 — 1750 | Netherlands

Rachel Ruysch

1779 — 1862 | Netherlands

Maria Margaretha van Os

1703 — 1783 | Bavaria

Barbara Regina Dietzsch

1699 — Scotland | 1758 — Great Britain

Elizabeth Blackwell

1747 — Bavaria | 1794 — Great Britain

Maria Katharina Prestel

1954 | United Kingdom

Prue Venables

1881 — 1965 | Bulgaria

Elisaveta Georgieva Konsulova-Vazova

1941 | Turkey

Nur Koçak

1950 — 2006 | Lithuania

Elvyra Kairiūkštytė

1752 — 1794 | France

Anne-Rosalie Bocquet Filleul

1955 | Japan

Michiko Kon

1874 — 1948 | United States

Fra Broadwell Dinwiddie Dana

1772 — 1855 | France

Marie-Victoire Jaquotot

1878 — 1961 | USA

Josephine Hale

1609 — 1696 | France

Louise Moillon

1907 — 1988 | Taiwan

Chen Chin

1896 — Latvia | 1965 — Estonia

Lydia Mei

1611 — 1691 | Italy

Anna Stanchi

1614 — | 1689 — Southern Netherlands

Michaelina Wautier

1952 | Ethiopia

Desta Hagos

1939 — 2017 | Singapore

Lee Boon Ngan

1935 — 2012 | Indonesia