Research

During my tenure as the editorial director of Revue Noire magazine in the 1990s, I was constantly seeking out women artists during my travels to various African capitals. In 2007, I was invited to write the chapter on Africa for the catalogue of the Global Feminisms exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. This experience motivated me to learn more about pioneering women visual artists on the African continent and to contribute to fill the gaps in the history of African art. Consequently, I began encouraging young scholars and institutions to undertake similar initiatives. In 2015, the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. entrusted me with the task of developing a new programme for women artists. However, the subsequent director chose not to implement it.

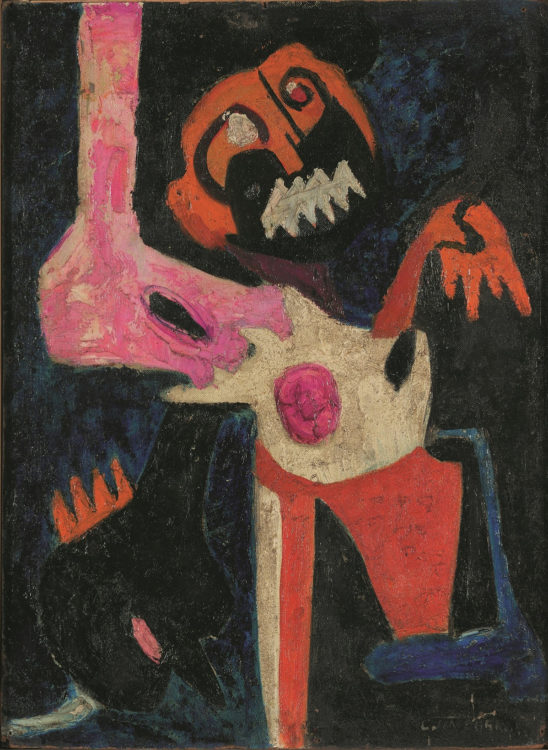

Bertina Lopes, La vita è una eruzione volcanica [Life is a Volcanic Eruption], 1997, oil on canvas, 140 x 160 cm, © Bertina Lopes

Antoinette Lubaki, Untitled, ca. 1929, watercolor on paper, 55 x 73,5 cm, Courtesy Magnin-A, Paris, © Antoinette Lubaki, © Photo: Fabrice Gousset, Courtesy Cornette de Saint Cyr, Paris

Wissam Fahmy, fataat nubia [Nubian Girl], 1973, oil on canvas, 65 x 55 cm

The Africa2020 Season in France, which I designed and led from 2018 to 2021, provided me with a significant opportunity for advancement. The Focus Femmes [Women Focus]1, one of the three pillars of this unprecedented project, spotlighted African women in the arts, sciences and entrepreneurship. Among the thirty projects in this Focus, nine were art exhibitions featuring only women and curated by women art workers from Africa and its diasporas. In partnership with AWARE, I established a scientific committee to organise a symposium, “Reclaim: Narratives of African Women Artists“2, held online in April 2021, and a series of publications on pioneering African women artists. The Njabala Foundation in Kampala, Uganda, founded by Martha Kazungu in 2021, emerged from that programme. Our collaboration with AWARE continues, and since then, more publications on women artists from Africa have been added to the AWARE website through a second project, “Tracing a decade: Women artists of the 1960s in Africa“.3 The ongoing challenge for all involved in this long-term venture is to research and identify, country by country, the numerous pioneering African women artists who are missing from art history books and exhibitions on Modern art. Taking the sixties as a marker, a symposium of the same name4 was held in Kampala in March 2024, representing another step in reclaiming the narrative of global art history. Known as “The Year of Africa”, 1960 marked the moment when seventeen African territories gained independence from France, Belgium and the United Kingdom, sparking the promise of a bright new future driven by demands for emancipation and social justice. While African male activists involved in the liberation struggles are always celebrated, the role of women is often overlooked, as if they had no part to play. Some scholars have been diligently sharing their research, addressing the gaps in history that have, whether by accident or design, overlooked the contributions of women intellectuals, activists and artists who were active during those challenging times.

In the iconic group photograph of the first Congress of Black Writers and Artists held at the Sorbonne University in Paris in 1956, there is only one woman present: Martinican Paulette Nardal. Co-founder of the bilingual French-English publication La Revue du monde noir – The Review of the Black World, in Paris in 1931, P. Nardal is a largely unrecognised mastermind of the Negritude movement. Her writings and vision were instrumental in shaping the political, intellectual and artistic discourses that fuelled numerous liberation movements across the African continent. A year later, in 1957, the British colony known as the Gold Coast became the first West African territory to achieve independence. How many people – including Ghanaians – know that the country’s flag, first hoisted on Ghana’s Independence Day on 6 March 1957, was designed by Theodosia Salome Okoh (1922–2015), a Ghanaian stateswoman, sportswoman, teacher and artist?

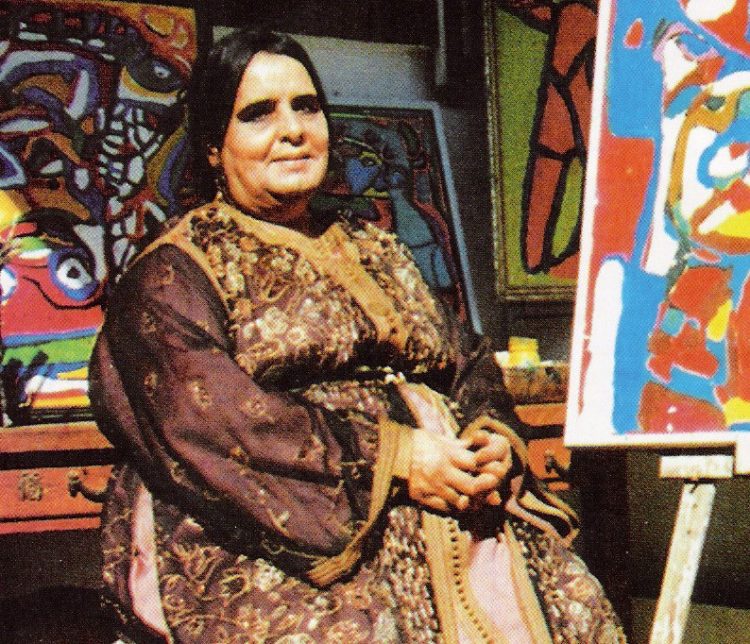

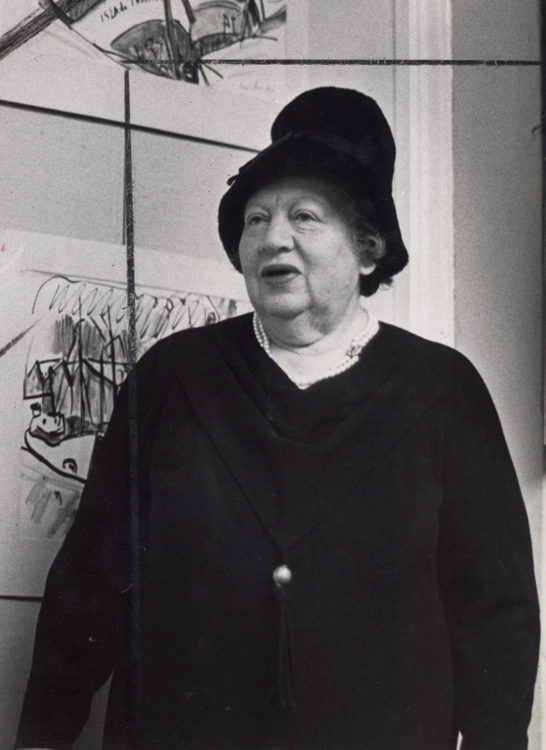

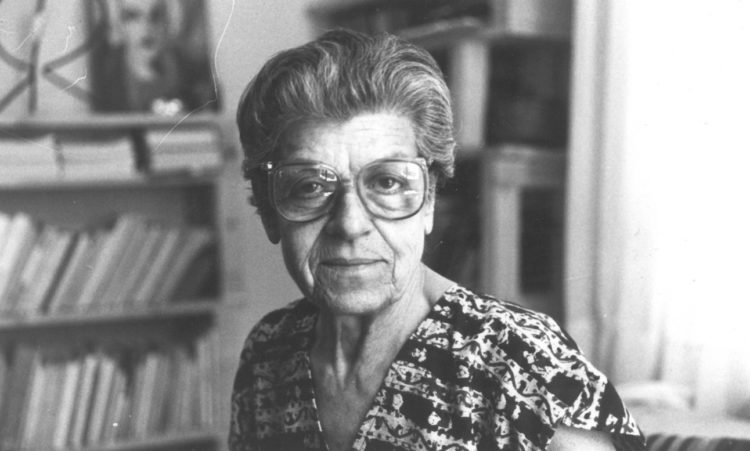

Suzanne Wenger © Photo : Wolfgang Denk

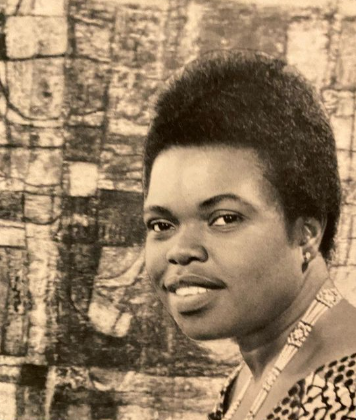

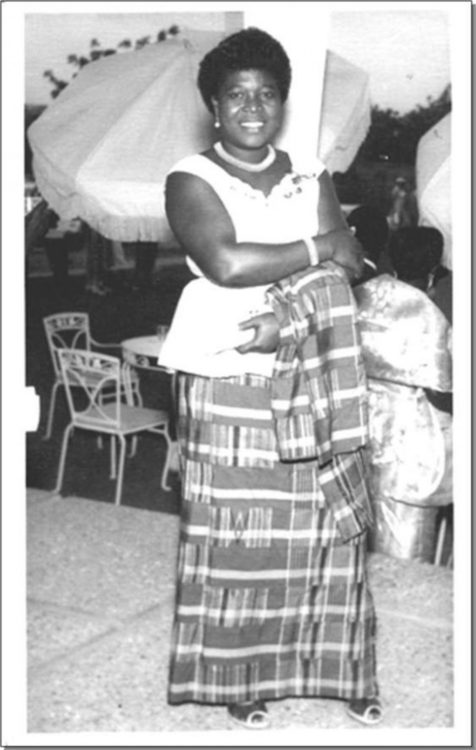

Portrait of Felicia Abban

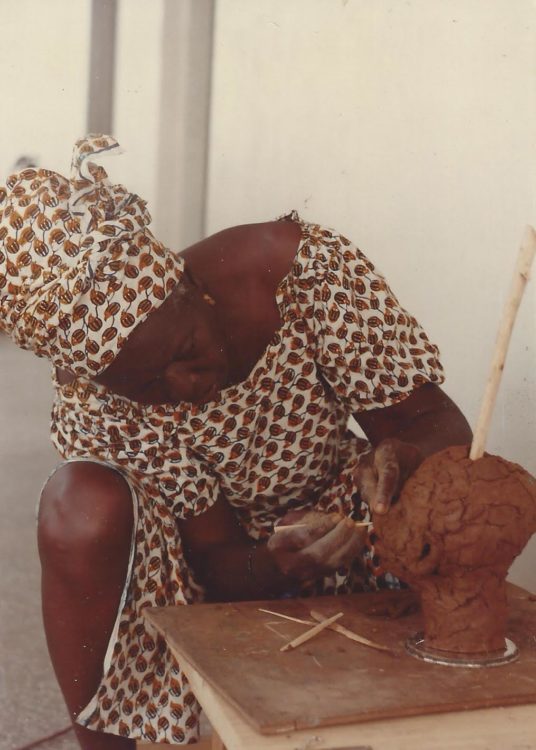

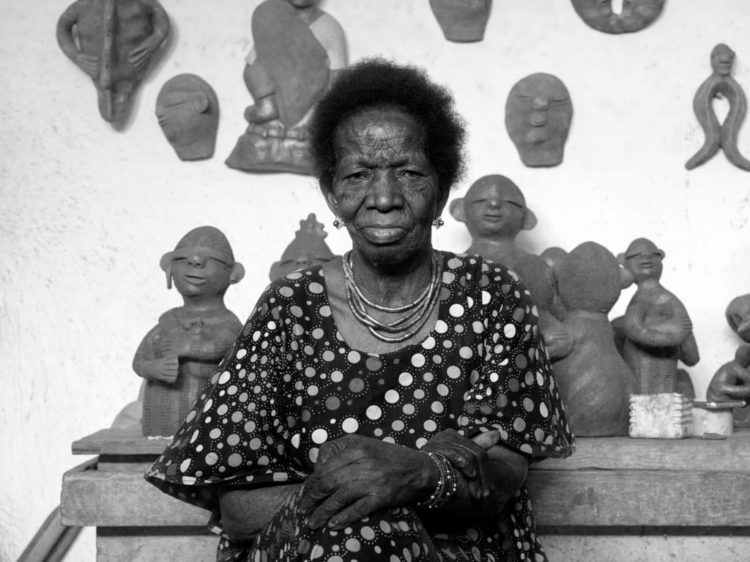

Grace Salome Kwami modelling clay heads at Gynyase, Kumasi, 1995. © Photo: Atta Kwami. Collection-Estate of Atta Kwami

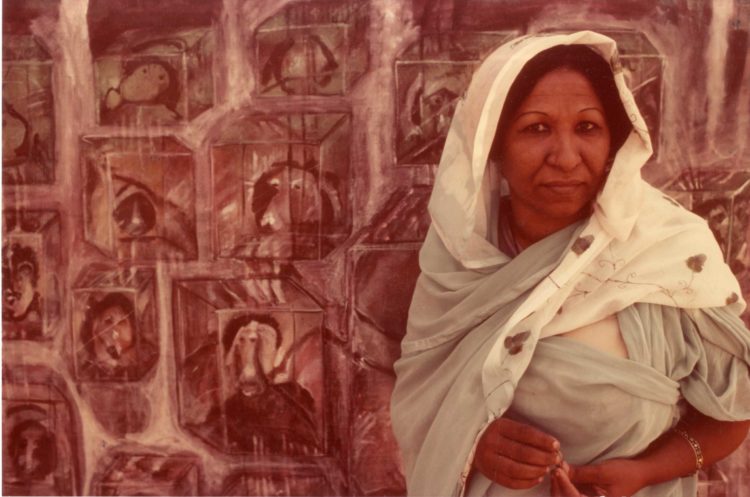

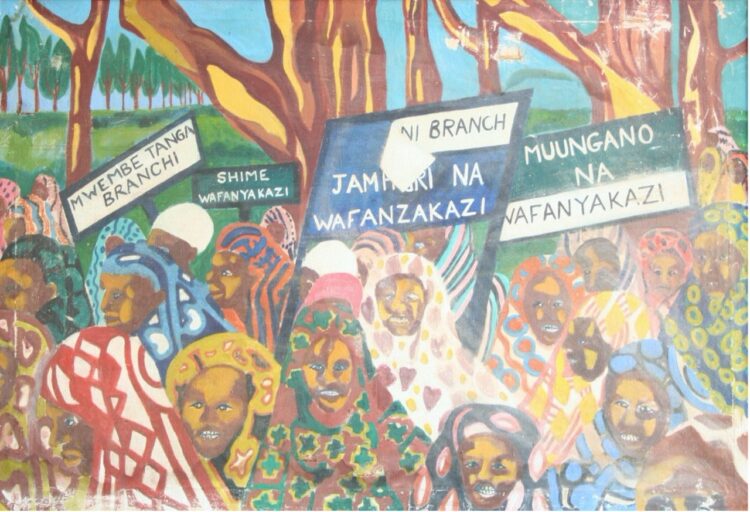

The era of independence in Africa saw the emergence of significant gatherings organised by women eager to play an active role in nation-building. The First Congress of the Union des femmes de l’Ouest africain (UFOA) [West African Women’s Union], held from 20 to 23 July 1959, in Bamako, Mali, highlighted the shared colonial histories and cultures within the region. This encouraged delegates from Guinea, Benin, Senegal and Mali to develop a sense of belonging to a “common African culture”. In the 1960s, this congress became a cornerstone in advancing “women-led Pan-Africanism” in francophone West Africa. On 1 August 1960, the Women’s Improvement Society of Nigeria inaugurated a twelve-day congress at the University of Ibadan. For the first time, fifty-five women from eight West African countries came together, bridging linguistic and colonial divides. The debates held during this congress laid the groundwork for the actions of national organisations and feminist theoretical developments in Africa over the subsequent decades. In July 1962, the Conference of African Women, hosted in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, welcomed representatives from a dozen resistance organisations across fourteen African countries. The conference championed the end of colonialism, the eradication of apartheid and segregation in all forms, and the inclusion of African women in political decision-making processes. Key outcomes included the formation of the African Women’s Union [now Pan-African Women’s Organization (PAWO)] and the establishment of African Women’s Day, to be celebrated annually on 31 July. The list of visual artists who participated in these gatherings is not yet available. However, several prominent figures were actively involved in the struggle for independence and social justice. Algerians Djamila Bent Mohamed (1933–2023) and Aïcha Haddad (1937–2005), along with Mozambicans Bertina Lopes (1924–2012) and Reinata Sadimba (1945–), were notable for their contributions to the fight for independence. Senegalese artist Younousse Sèye (1940–) publicly opposed Apartheid. Egyptian artist Inji Efflatoun (1924–1989), who was a member of the Cairo-based Art and Liberty Group (1938–1948), played a key role in the formation of the League of Young Women of Universities and Institutes in 1945. This group was dedicated to anti-colonial activism and the promotion of gender equality.

Colette Omogbai, Agony, c. 1963, Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth, © Colette Omogbai

Fatma Shaaban Abdalla Abubakar, The Revolutionary Spirit, 1960s, Courtesy of Makerere Art Gallery Collection

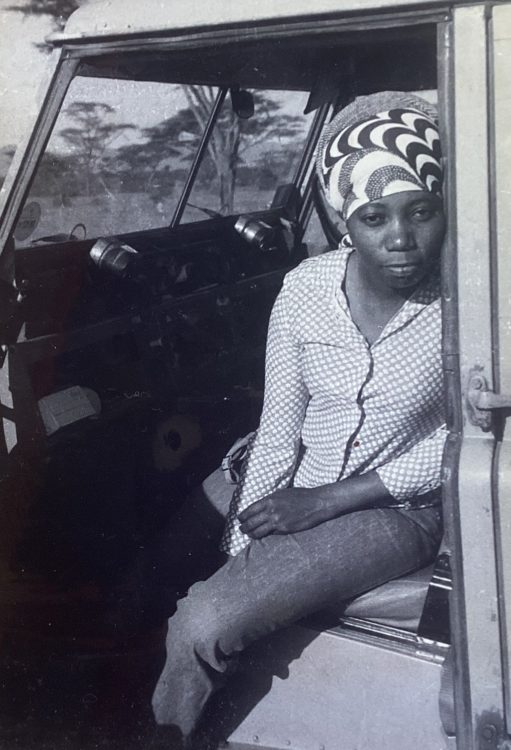

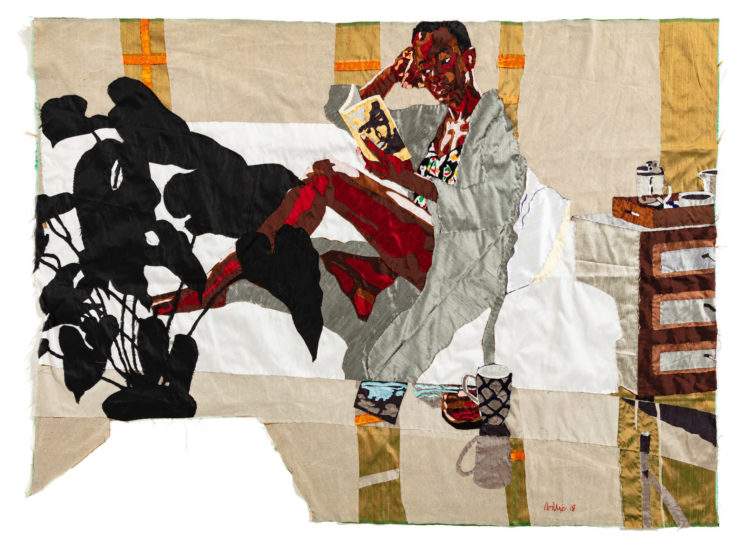

Theresa Musoke – Theresa Musoke’s Archives

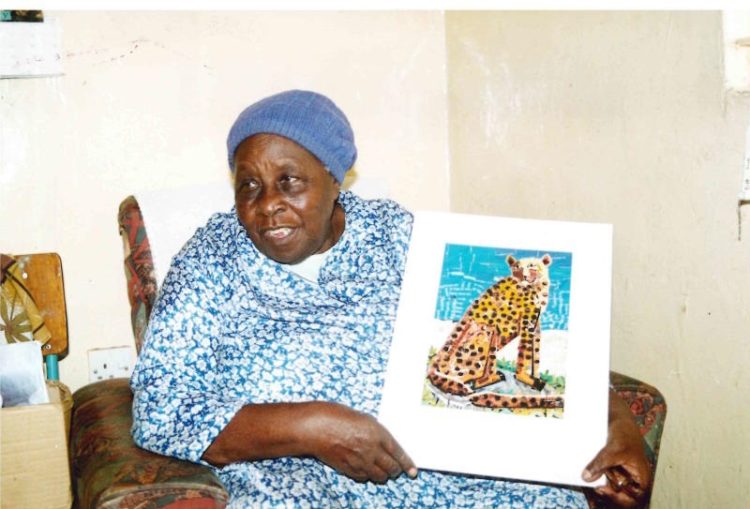

During the first decade of independence, several young African states leveraged culture as a tool for nation-building and soft power. A landmark example of this strategy was the 1966 World Festival of Negro Art held in Dakar, Senegal. Despite the widespread acclaim given to the participation of notable male figures such as Americans Duke Ellington and Alvin Ailey, Nigerian Wole Soyinka, Senegalese Douta Seck and Ousmane Sembène and Ivorian Christian Lattier, historians always seem to overlook the contributions of women. Out of the two hundred African artists featured in the contemporary art exhibition Tendances et Confrontations, held at Dakar’s Palais de Justice, only two women seem to have been included: Madeleine Razanadranaivo (dates?) and Hélène Razanatefy (dates?) from Madagascar. Although the two artists had together previously exhibited in France in December 1955, they have since been erased from the history of African art. Why were the many African women visual artists already practising in the sixties excluded from the festival’s exhibition? Nigerian artist Constance Afiong “Afi” Ekong (1930–2009), who had participated in group shows in Lagos with Ben Enwonwu (1917–1994), Uche Okeke (1933–2016), Bruce Onobrakpeya (1932–) and Demas Nwoko (1935–), was only invited to the conference on “Negritude and African Personality”. Where were Algerians Baya (1931–1998), Souhila Bel Bahar (1934–2023) and Leila Ferhat (1939–2020); Egyptians Amy Nimr (1898–1974) and Gazbia Sirry (1925–2021); Ghanaians Felicia Ewuraesi Abban (1935–2024) and Grace Salome Abra Anku Kwami (1923–2006); Kenyan Rosemary Namuli Karuga (1928–2021); Moroccan Chaïbia Tallal (1929–2004); Nigerians Colette Omogbai (1942–), Elizabeth Olowu (1938–) and Theresa Luck-Akinwale (1934–); Sierra Leonean Olayinka Miranda Burney-Nicol (1927–1996); South African Irma Stern (1894–1966); Tanzanian Fatma Shaaban Abdalla Abubakar (1939–1994); Tunisian Shasha Safir (1939–2018); and Ugandans Estelle Betty Manyolo (1934–1999) and Theresa Musoke (1944–)?

Artist Clara Etso Ugbodaga with her self-portrait and Nigerian Federal Commissioner Matthew Mbu, London, August 1st 1958. (Photo by John Franks/Keystone/Getty Images)

Safia Farhat, Dernière œuvre, 1990, weaving, 200 x 340 cm, © Musée Safia Farhat

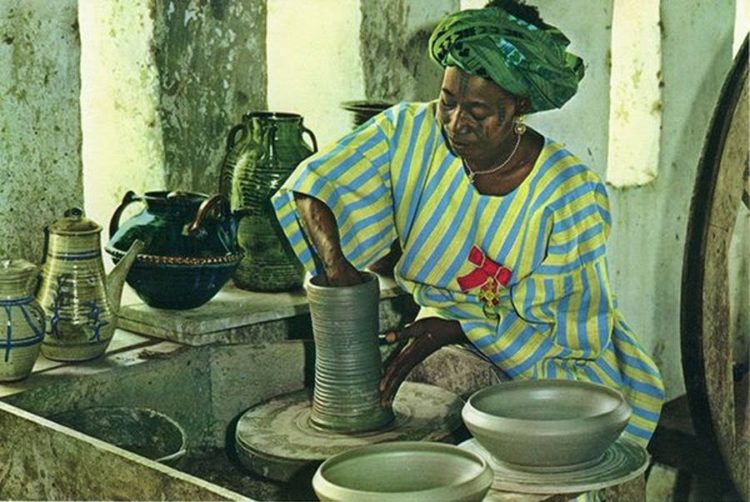

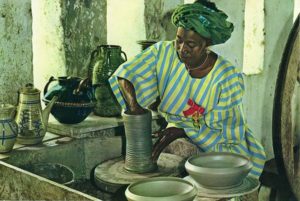

Postcard, “Woman Potter, Abuja, Northern Nigeria” [Ladi Kwali]. Photograph by John Hinde

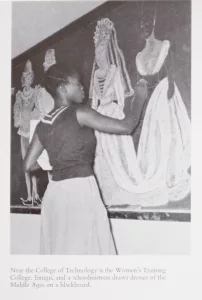

“Near the College of Technology is the Women’s Training College, Enugu, and a schoolmistress draws dresses of the Middle Ages on a blackboard.” in Nigeria in Pictures: A Pictorial Survey of the Federation of Nigeria in the Year of Independence. Lagos: The Information Division of the Federal Ministry of Information, 1960, © Photo: Ben Krewinkel/Africa in the Photobook

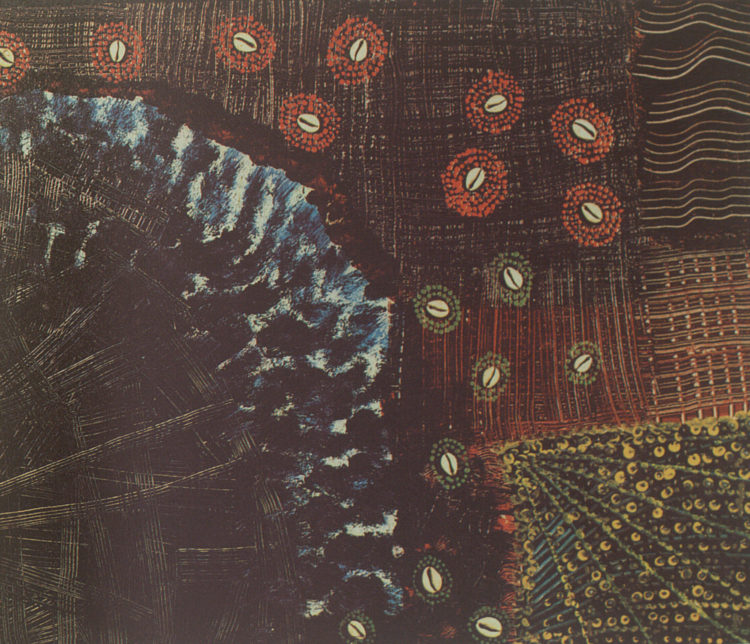

Regularly forgetting women artistic practitioners, historians often fail to mention the women who contributed to the artistic and conceptual revolutions that spread across the continent in the 1960s and 1970s. Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu (1928–2003), an influential faculty member at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (now Ahmadu Bello University) from 1955 to 1964, witnessed the birth of the Zaria Art Society in 1958, founded by university students U. Okeke, D. Nwoko, B. Onobrakpeya, Yusuf Grillo (1934–2021) and Erhabor Emokpae (1934–1984). Josephine Ifueko Omigie (1936–1997), a graduate of the College, became a member of the Society in 1959. In Tunisia, Safia Farhat (1924–2004), director of the Tunis Institute of Fine Arts from 1966, was the only woman involved in the École de Tunis movement that began in 1949. Despite Moroccan women artists like Malika Agueznay (1938–) appearing in numerous photographs of the École de Casablanca, they are only recently beginning to be systematically cited in captions and publications about this movement. However, it is virtually impossible to erase Sudanese artist Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq (1939–), a key member of the Crystalist Group and co-author of their manifesto, which was first published in the arts section of Khartoum’s Al-Ayyam newspaper on 21 January 1976.

All these artists were true champions, paving the way for future generations to blossom. They tackled the challenges of their time and led thriving lives as visual artists, educators, mothers, activists, wives, and mothers. Nigerian Ladi Kwali (1925–1984), whose image appeared on the back of the 20 Naira banknote from 2006 to 2022, is the only artist and one of only three women – alongside Tunisian physician Tawhida Ben Cheikh and Malawian politician Rose Lomathinda Chibambo – to have received this honour in Africa as of 2024. While this recognition is a good start, it is far from sufficient. Widely acknowledging and celebrating all these visionary pioneers is long overdue. Both the Africa2020 Season symposium Reclaim: Narratives of African Women Artists and the Tracing a Decade: Women Artists of the 1960s in Africa symposium in Kampala in March 2024 brought together researchers from Algeria, Ghana, France, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda and the USA. Since 2019, we – I, AWARE, Njabala and many other collectives and individuals – have been collaborating and sharing this collective knowledge with audiences worldwide. This effort will continue with the contributions of emerging scholars, as this journey has no end.

« Focus femmes », Saison Africa2020, 2020, https://www.saisonafrica2020.com/en/women-focus.

2

« Reclaim: Narratives of African Women Artists », AWARE, June 30, 2024.

3

AWARE’s website – Project page – Tracing a decade: Women artists of the 1960 in Africa

4

« Symposium. Tracing a Decade: Women Artists of the 1960s in Africa », AWARE, 2024, https://awarewomenartists.com/en/nos_evenements/tracer-une-decennie-artistes-femmes-des-annees-1960-en-afrique/.

N’Goné Fall is an independent curator and cultural policies specialist. She has been the editorial director of the Paris-based contemporary African art magazine Revue Noire from 1994 to 2001. She curated exhibitions in Africa, Europe, and the United States. She was one of the curators of the African Photography Encounters in Bamako, Mali, in 2001, and a guest curator at the 2002 Dakar Biennale in Senegal. She is the author of strategic plans and evaluation reports for national and international institutions. She has also been a professor at the Senghor University in Alexandria, Egypt, and a lecturer at the Michaelis school of arts in Cape Town, South Africa, and at the Abdou Moumouni University in Niamey, Niger. She was the General Commissioner of the Africa2020 Season, a series of more than 1,500 cultural, scientific, and pedagogical events held all over France from December 2020 to September 2021. Since 2023 she has been part of the academic committee of AWARE: Archive of Women Artists, Research & Exhibitions and the Njabala Foundation’s programme, Tracing a decade: Women artists of the 1960s in Africa.

N’Goné Fall, "Paving the way: Women artists and Independence in Africa." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/ouvrir-la-voie-artistes-femmes-et-independance-en-afrique/. Accessed 7 February 2026