Focus

Marta Pan, Lentilles flottantes, 1994, casted resin, Ø 210 cm x 105 cm, Ø 82.7 x 41.4 in., Courtesy Galerie Mitterrand, © Fondation Marta Pan-André Wogenscky

Camille Claudel (1864-1943) appears to be the embodiment of French female sculptors, yet she was not the exception to the rule, as women have sculpted and continue to sculpt today. Sculpture is a costly, technical and psychical practice, yet that has not stopped women from investing in it. At the beginning of the twentieth century financial pressures pushed female creators to sell their works by engaging with fashionable trends such as bestiaries, as was the case for Jane Poupelet (1874-1932) and Renée Sintenis (1888-1965), who made reputations for themselves in the art world.

Certain women took up chisels to respond to official commissions that allowed them to work with large-scale stones and to durably inscribe their works into public space. In Buenos Aires the Fuente de las Nereidas (1903) was made by Lola Mora (1867-1936), one of the best-known female Argentinian sculptors. Symbol of the Stalinist regime, erected for the USSR Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, Worker and Kolkhoz Woman by Vera Ignatevna Moukhina (1889-1953) is also a good example of a monumental and public sculpture realised by a woman. In these exercises, some women compete with men, such as Anna Semyonovna Goloubkina (1864-1927) as she sculpted one of the doors of the Muscovite opera house in a clear response to the Gates of Hell of her French master Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). (It was also through representing important personalities of their time that these sculptors became well-known: A. Golubkina realised a portrait gallery amongst including poet and writer Andrei Bely (1907). As for Augusta Savage (1892-1962), she sculpted in clay the illustrious faces of the African American community.

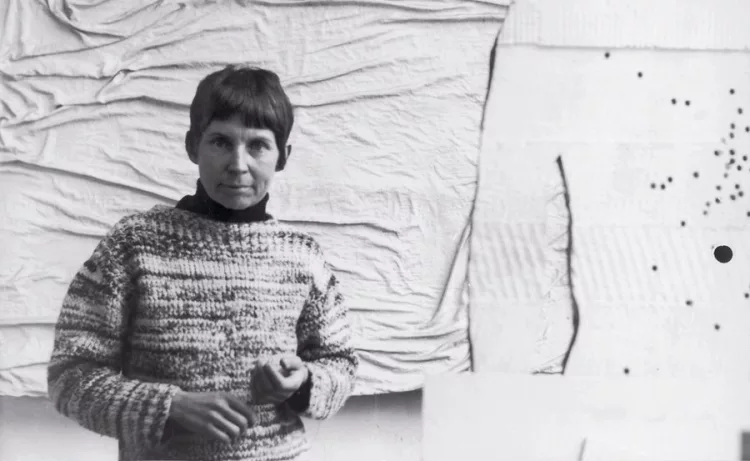

Women artists also initiated a reflection on the artworks’ environment. Germaine Richier (1902-1959) maintained a classical approach to the body and played with the plinth, which became its constituent element. At the same time, Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) was interested in the ovoid forms she fashioned from industrial materials. This innovation changed the artist’s relationship to the material: stone was cut, plastic was bent, steel was twisted. Artworks adapted and responded to the spaces in which they were installed. Marta Pan (1923-2008) played with double reflections in water and metal, whereas Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017) realised sculptures that could be transposed into various materials – wood, stone, metal, terracotta and fiberglass – and whose scale ranged from the minuscule to the monumental.

Questions about form and the body have inhabited both modern and contemporary women sculptors who have made it a powerful tool for dissent. This can be seen not only in the work of Tayeba Begum Lipi (b. 1969), who projected her own face onto mannequins wearing niqabs and chadors in her installation Toys Are Watching Toys (2002) to denounce the Islamisation of Bangladeshi society. It is also evident in the work of Berlinde de Bruyckere (b. 1964), where suffering bodies made of pale wax are adorned with elements of Christian iconography, such as the long hair of Mary Magdalene.

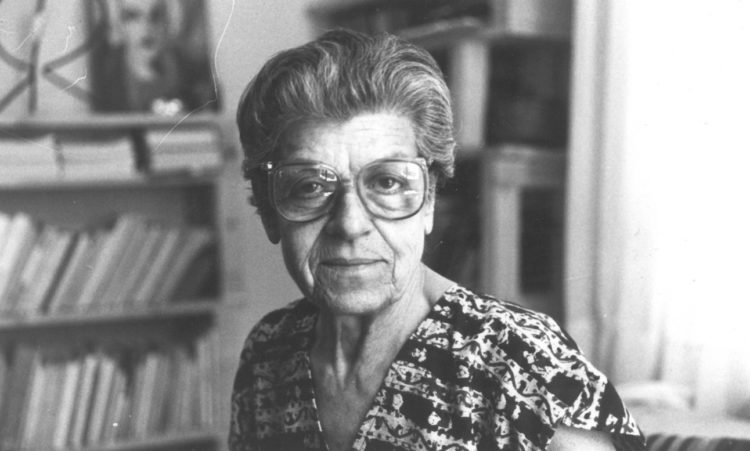

Recently, the work of Marie Orensanz (b. 1936) has benefited from renewed recognition as she was awarded the AWARE 2020 Outstanding Merit Prize. Today the work of female sculptors have recognition and have been celebrated in exhibitions such as Sculpture’Elles : Les sculpteurs femme du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours (2011) at the Musée des Années 30 in Boulogne-Billancourt, France, as well as in Anne Rivière’s publication Dictionnaire des sculptrices en France (2018) that inventories the work of many women artists who remain little known.

1864 — 1943 | France

Camille Claudel

1874 — 1932 | France

Jane Poupelet

1888 — Poland | 1965 — Germany

Renée Sintenis

1867 — 1936 | Argentina

Lola Mora

1889 — Latvia | 1953 — Russia

Vera Moukhina

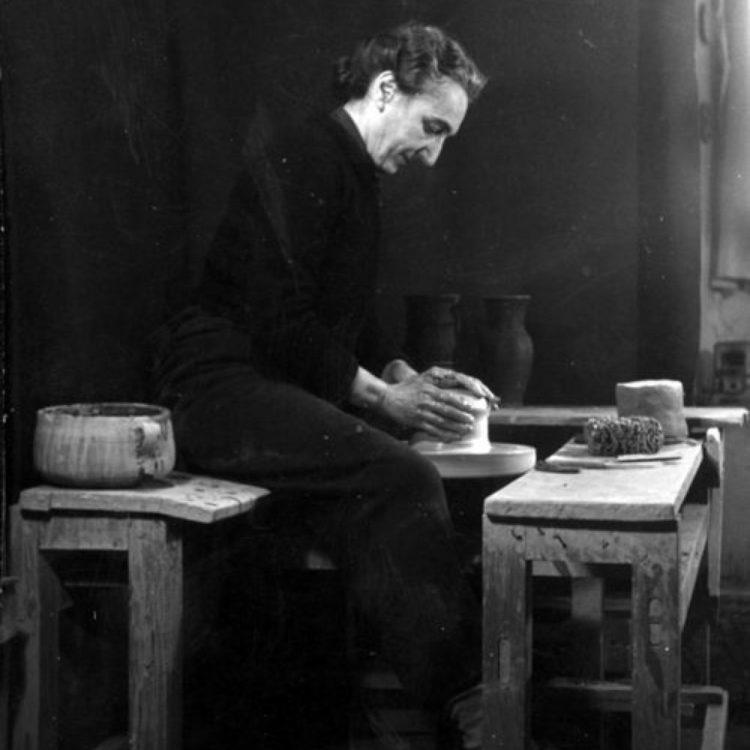

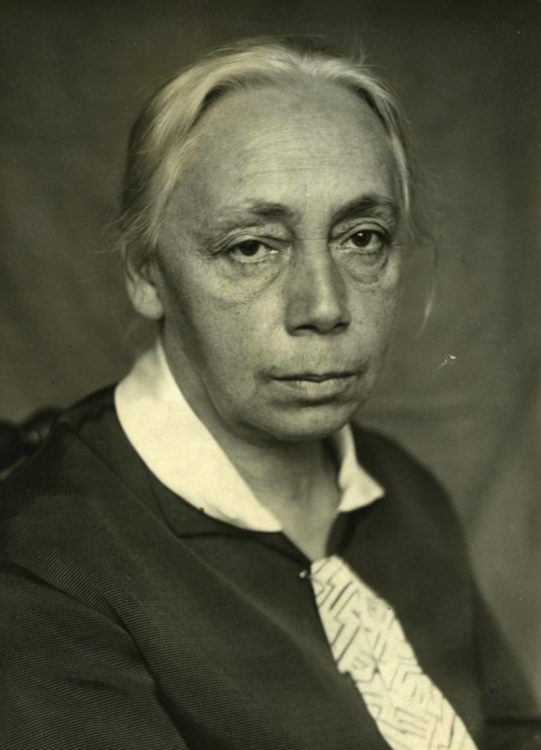

1864 — 1927 | Russia

Anna Goloubkina

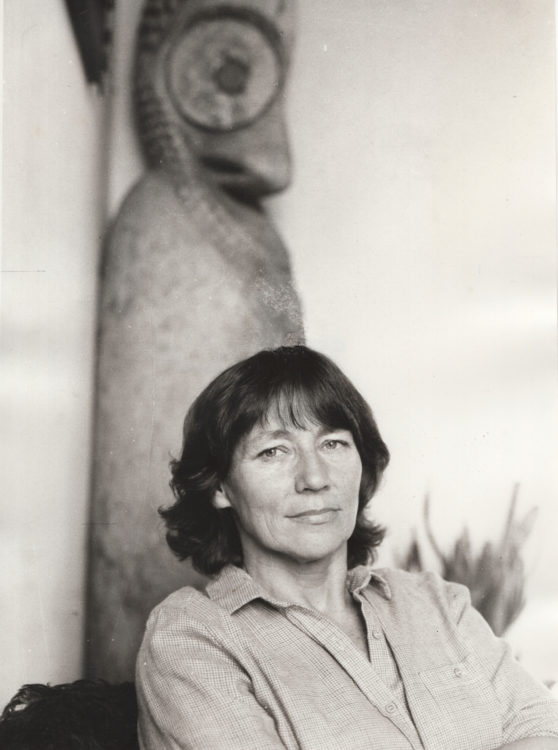

1902 — 1959 | France

Germaine Richier

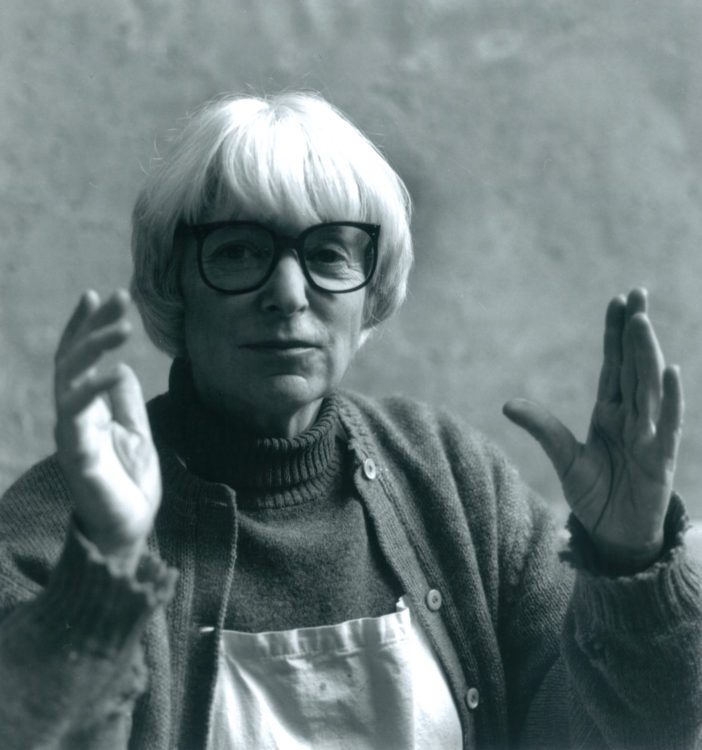

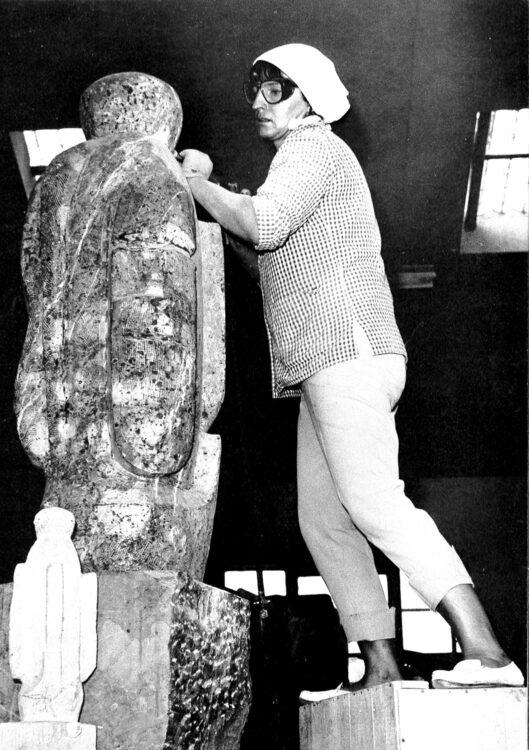

1903 — 1975 | United Kingdom

Barbara Hepworth

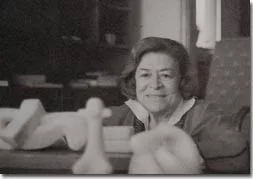

1923 — Hungary | 2008 — France

Marta Pan

1916 — 2017 | Lebanon

Saloua Raouda Choucair

1969 | Bangladesh

Tayeba Begum Lipi

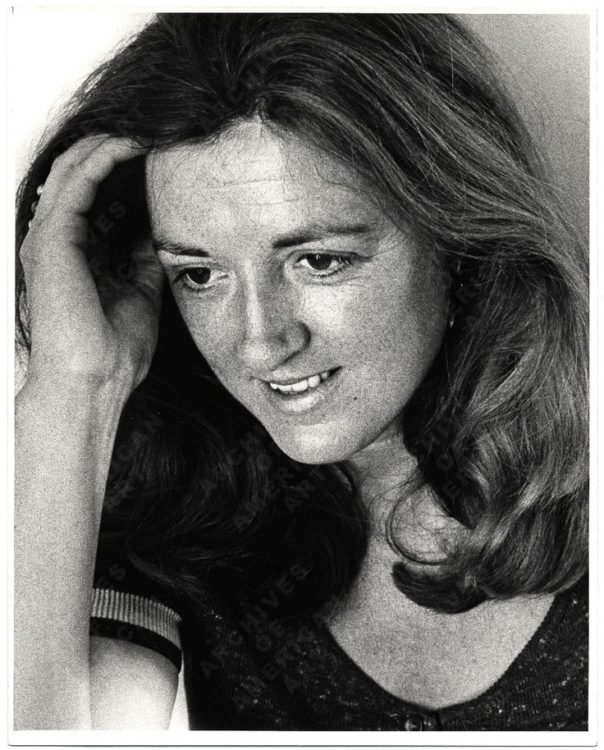

1964 | Belgium

Berlinde De Bruyckere

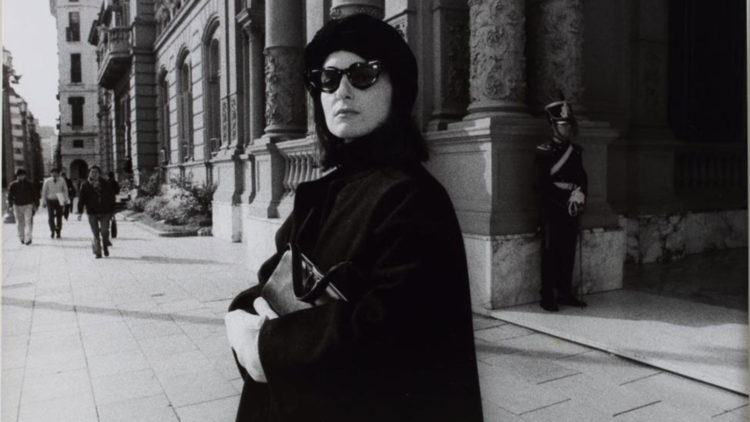

1936 | Argentina

Marie Orensanz

1911 — Chile | 1952 — France

Juana Muller

1922 — 2019 | Iran

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

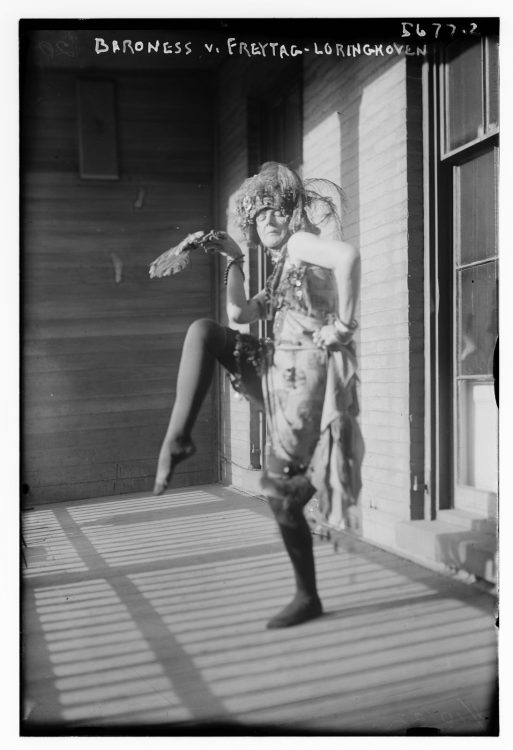

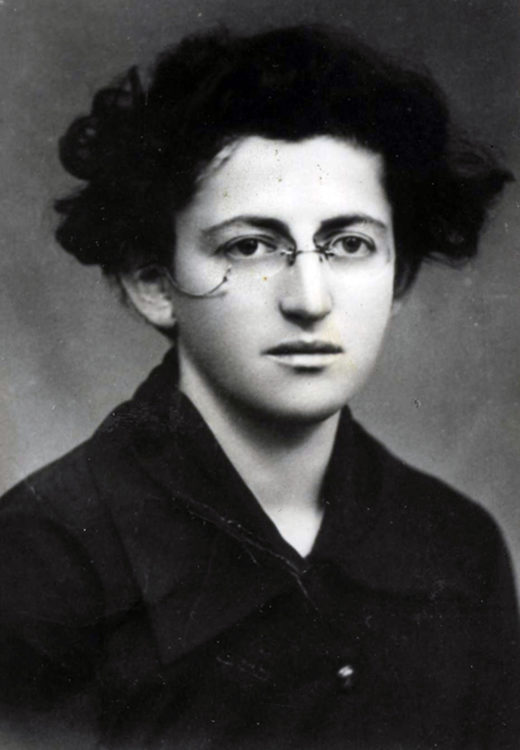

1874 — Poland | 1927 — France

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

1888 — Ukraine | 1968 — Israel

Chana Orloff

1894 — 1973 | Brazil

Maria Martins

1953 | Bolivia

Carmen Perrin

1869 — 1940 | United States

Janet Scudder

1911 — Denmark | 1984 — France

Sonja Ferlov Mancoba

1863 — France | 1946 — ?

Marcelle Renée Lancelot-Croce

1877 — 1967 | France

Geneviève Granger

1836 — Switzerland | 1879 — Italy

Marcello (Adèle d’Affry, duchesse de Castiglione Colonna, dite)

1844 — 1923 | France

Sarah Bernhardt

1825 — 1909 | France

Hélène Bertaux

1828 — 1888 | France

Claude Vignon (Marie-Noémi Cadiot-Constant Rouvier, dite)

1844 — 1924 | France

Marie Cazin

1878 — 1954 | Germany

Clara Rilke-Westhoff

1859 — 1926 | France

Blanche Adèle Moria

1940 | United States

Nancy Grossman

1971 | United States

Shinique Smith

1969 | Mexico

Paula Santiago

1894 — 1974 | Italy

Regina Cassolo Bracchi

1970 | Brazil

Lídia Lisboa

1926 — 2013 | United States

Ruth Asawa

1964 | Argentina

Nicola Costantino

1948 | United States

Joyce J. Scott

1961 | Jamaica

Jasmine Thomas-Girvan

1902 — Germany | 1998 — Israel

Hedwig Grossman Lehmann

1951 — 1994 | Argentina

Liliana Maresca

1959 | Australia

Linda Marrinon

1867 — Russia | 1945 — Germany

Käthe Kollwitz

1946 | United States

Alice Aycock

1948 | Brazil

Sonia Gomes

1963 | United Kingdom

Rachel Whiteread

1960 | Israel

Etti Abergel

1923 | Canada

Françoise Sullivan

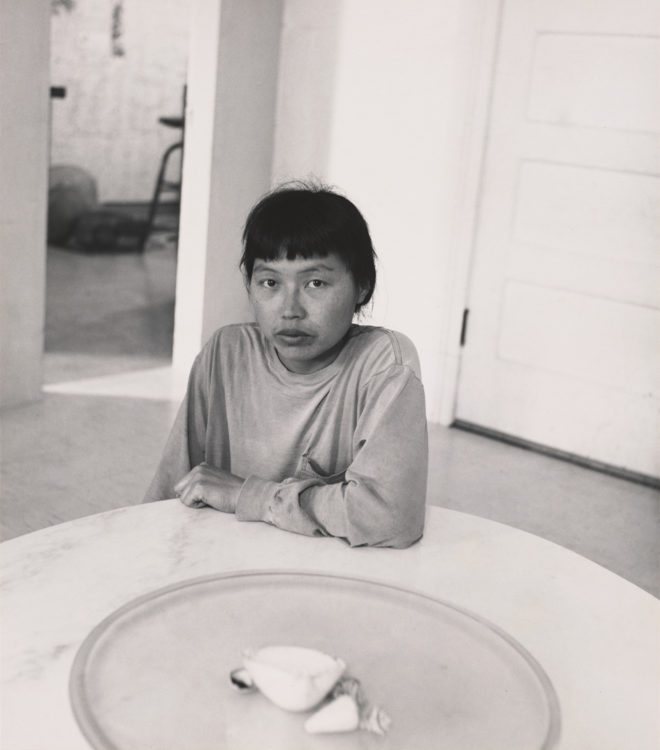

1969 | Hong Kong

MAN Phoebe Ching Ying

1967 | Japan

Mariko Mori

1964 | France

Françoise Pétrovitch

1911 — Switzerland | 1990 — France

Isabelle Waldberg

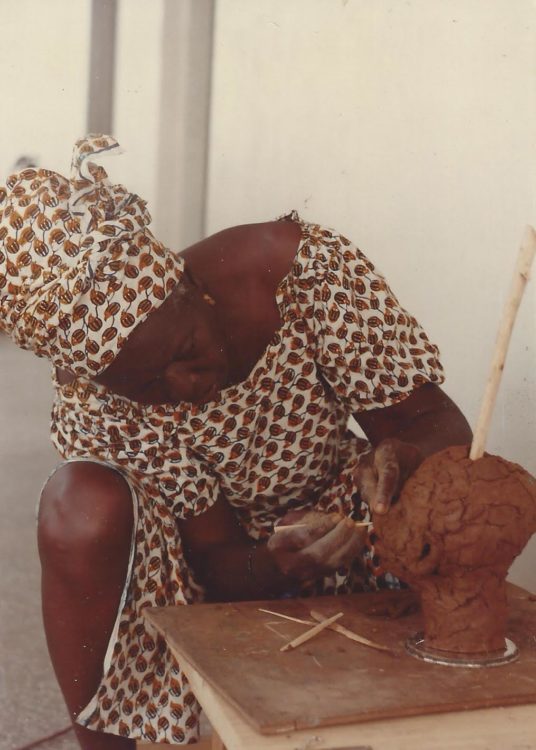

1945 — 2026 | Senegal

Seni Awa Camara

1905 — Moldova | 1990 — France

Ida Karskaya

1938 | Latvia

Vija Celmins

1885 — 1966 | United States

Malvina Hoffman

1930 — 2017 | Poland

Magdalena Abakanowicz

1946 | France

Dorothée Selz

1962 | United Kingdom

Sarah Lucas

1961 | Thailand

Pinaree Sanpitak

1936 — Germany | 1970 — United States

Eva Hesse

1876 — United States | 1973 — France

Anna Hyatt Huntington

1876 — Austria | 1956 — Hungary

Elza Kövesházi Kalmár

1949 | Turkey

Ayşe Erkmen

1926 — 2015 | France

Claude de Soria

1936 | France

Parvine Curie

1933 — Colombia | 1982 — France

Feliza Bursztyn

1909 — 1981 | Martinique, France

Marie-Thérèse Julien Lung-Fou

1923 — Poland | 2008 — Italy

Maria Papa Rostkowska

1947 | Mandatory Palestine

Nechama Golan

1965 | Sierra Leone

Patricia Piccinini

1968 | Poland

Joanna Rajkowska

1958 | United States

Renee Stout

1959 — 2006 | Australia

Bronwyn Oliver

1959 | Australia

Polly Borland

1925 — 2019 | Norway

Aase Texmon Rygh

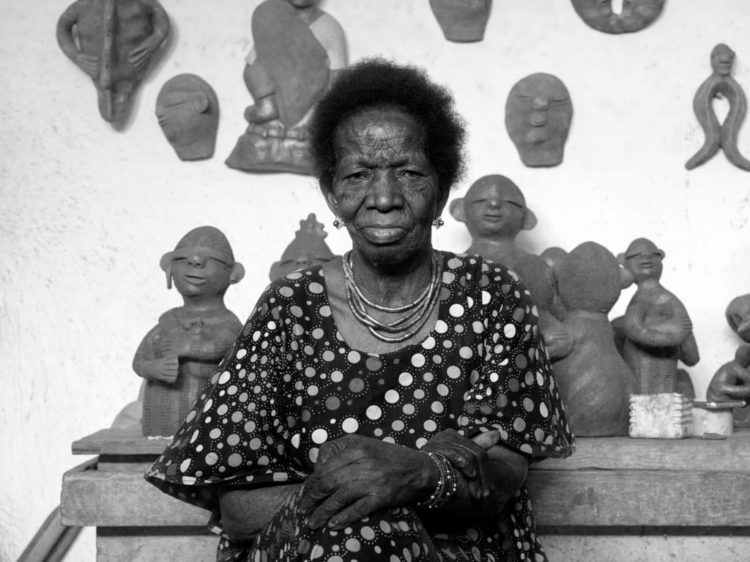

1923 — 2006 | Ghana

Grace Salome Kwami

1725 — British America (currently the United States) | 1786 — Great Britain (currently the United Kingdom)

Patience Lovell Wright

1965 | Spain

Ángela de la Cruz

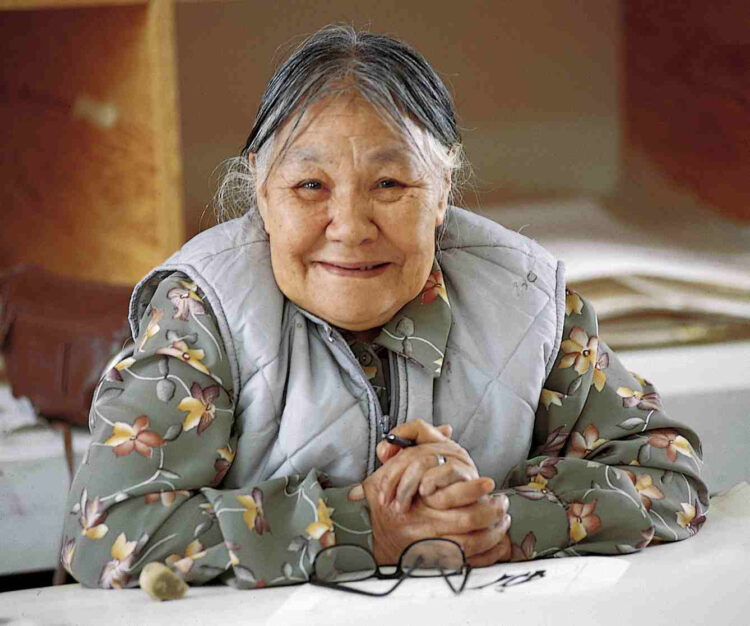

1927 — 2013 | Canada

Kenojuak Ashevak

1945 | Mozambique

Reinata Sadimba

1748 — 1821 | France

Marie-Anne Collot

1920 — 2002 | Vietnam

Điềm Phùng Thị

1775 — Great Britain | 1860 — United Kingdom

Catherine Andras

1950 | Israel

Drora Dominey

1934 | Belgium

Marianne Berenhaut

1918 — 1991 | Brazil

Judith Bacci

1928 — 2013 | Australia

Norma Redpath

1973 | Australia

Yhonnie Scarce

1957 | Philippines

Lani Maestro

1934 — 2023 | Germany

Mary Bauermeister

1915 — 1999 | Curaçao

May Henriquez

1923 — Lithuania | 2019 — United States

Aleksandra Kasuba

1812 — 1877 | France

Marie-Louise Lefèvre-Deumier

1770 — 1845 | France

Marguerite Julie Charpentier

1906 — Iraq | 1986 — Lebanon

Mouazzaz Rawda

1919 — 1989 | Indonesia

Trijoto Abdullah

1929 — 2014 | Japan

Aiko Miyawaki

1928 — 1980 | Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic)

Eva Kmentová

1895 — Latvia | 1969 — Estonia

Kristine Mei

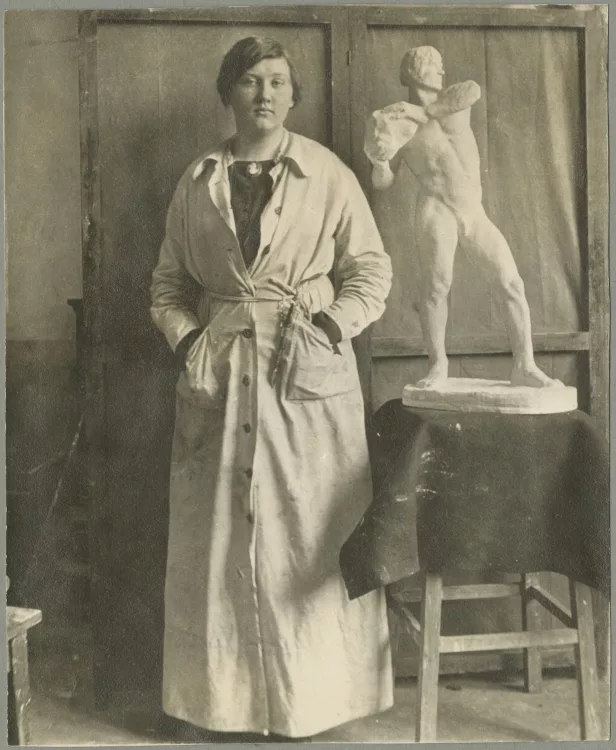

1863 — 1945 | Denmark

Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen

1973 | Denmark

Jeannette Ehlers

1900 — Ukraine | 1992 — Israel

Batia Lishansky

1930 — Bélarus | 2021 — Pologne

Wanda Czełkowska

1949 | Zimbabwe

Annastasia Munyawarara (Anna Mariga)

1975 | United Kingdom

Lucy Skaer

1975 | France

Eva Jospin

1934 | Indonesia