Focus

In the 19th century, as the discipline of the history of art was beginning to take form, a debate arose as to the origins of this art. The act of transforming plant or animal matter into fibre and then into fabric had long been considered a fundamental moment in cultural production, but textile practices were also attributed to a feminine, domestic sphere, and thus excluded from the theorisation of art. Certain high-quality textiles – created by men – were recognised as having influenced artistic development, but on the whole, textile work was left out of the modern canon. This reflects the discourse surrounding art’s supposed autonomy and the applied arts as set in opposition to the fine arts, underlining the subordinance of ‘tactile’ textile art to the optical art of painting.

From the first stirrings of the avant-garde to the turn of the 20th century, women artists were exploring the techniques and materials of textile art. Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979) designed and sewed costumes for several ballets, their patchwork motifs coming to life on the bodies they adorned. Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943) conceived embroidered and woven compositions for carpets or cushion covers, as well as beaded objects. But the idea of textiles as one of the mediums of modern art is seen as beginning with the Bauhaus, when the practice was first theorised. In the school’s weaving workshops, Gunta Stölzl (1897–1983), Otti Berger (1898–1944) and Anni Albers (1899–1994), amongst others, would combine their formal artistic research with industrial experimentation. Though their early works took a pictorial approach, weaving ‘paintings’ in wool, this would evolve into a methodology more specific to the medium, that recognised the particular quality of textiles as an interface between the haptic and optic worlds.

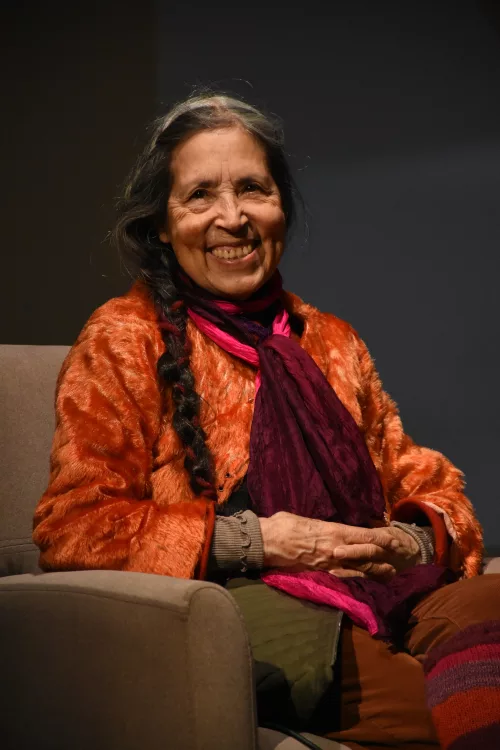

In the 1960s, the Fiber Art movement continued to develop an individual approach to the textile, in line with contemporary theories of aesthetics. Claire Zeisler (1903–1991), Lenore Tawney (1907–2007), Olga de Amaral (1932–) and Sheila Hicks (1934–) liberated artworks from their looms and transformed them into sculptures. It was considered a moment of emancipation, the medium breaking free from its utilitarian function and establishing itself as an object in the contemporary art world.

Within the feminist art movement of the 1970s, artists like Miriam Schapiro (1923–2015), Faith Ringgold (1930–2024) and Annette Messager (b. 1943) turned to textile practices previously considered ‘minor’ in order to explore their particular qualities, shining light on the long-neglected lives, labours and creativity of women. The opposition between art and crafts was shown to rest on social hierarchies drawn along racial and gender lines, while at the same time serving to reinforce these hierarchies, as the allegedly intuitive manual skills of women became a basis to deny them any creative faculty.

Today, numerous artists, such as Ntombephi Ntobela (b. 1966), Marie Watt (b. 1967) and Yee I-Lann (b. 1971), continue to explore the materials and techniques of textile art, drawing on the transmission of knowledge from different cultures throughout the world. They continue to question, revitalise and perhaps even further develop these practices. In this way, they contribute to an ongoing revaluation of textiles in the art world, and an examination of the supposed separation between the creation of art works and the production of ethnological objects.

1899 — Germany | 1994 — United States

Anni Albers

1943 | France

Annette Messager

1936 — Jamaica | 2017 — France

Hessie (Hessie Djuric, née Johnston, dite)

1939 | France

Raymonde Arcier

1934 | United States

Sheila Hicks

1889 — 1943 | Switzerland

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

1911 — France | 2010 — United States

Louise Bourgeois

1963 | Egypt

Ghada Amer

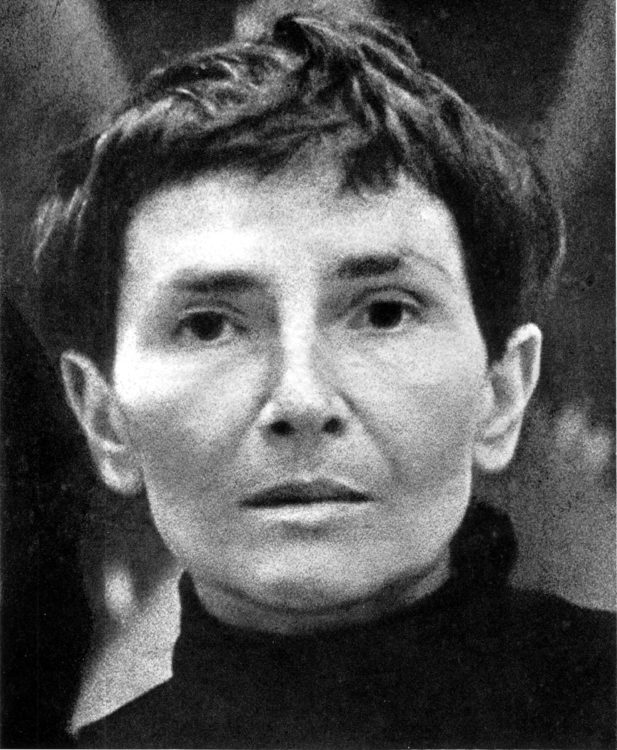

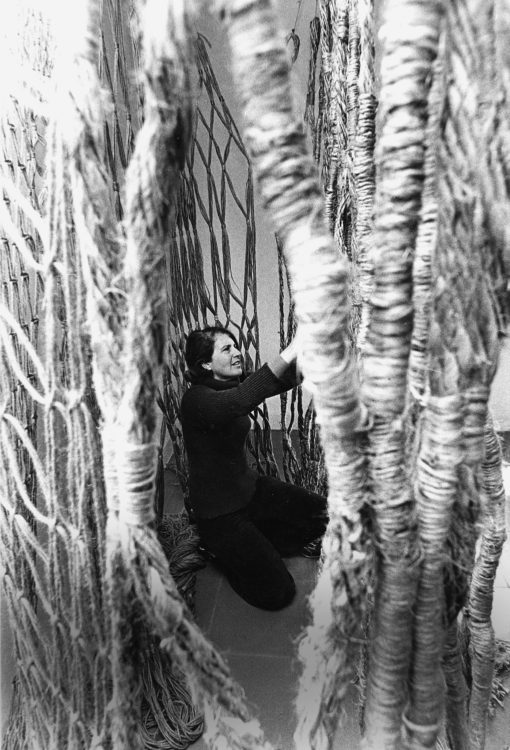

1930 — 2017 | Poland

Magdalena Abakanowicz

1925 — Switzerland | 2015 — France

Eva Aeppli

1963 | India

Rina Banerjee

1939 | France

Bernadette Bour

1926 — 2018 | Romania

Geta Brătescu

1931 — 2019 | Lebanon

Huguette Caland

1969 | Vietnam

Tiffany Chung

1932 | Colombia

Olga de Amaral

1963 | United Kingdom

Tracey Emin

1942 | United States

Jann Haworth

1908 — Ukraine | 1958 — Poland

Maria Jarema

1944 | Australia

Yvonne Koolmatrie

1892 — Poland | 1966 — France

Jeanne Kosnick-Kloss

1958 | Ireland

Kathy Prendergast

1929 — Japan | 2025 — Germany

Takako Saito

1961 | China

Lin Tianmiao

1942 | New Zealand

Maureen Lander

1907 — 2007 | United States

Lenore Tawney

1966 | Zambia

Agnes Buya Yombwe

1940 | Argentina

Delia Cancela

1971 | New Zealand

Ani O’Neill

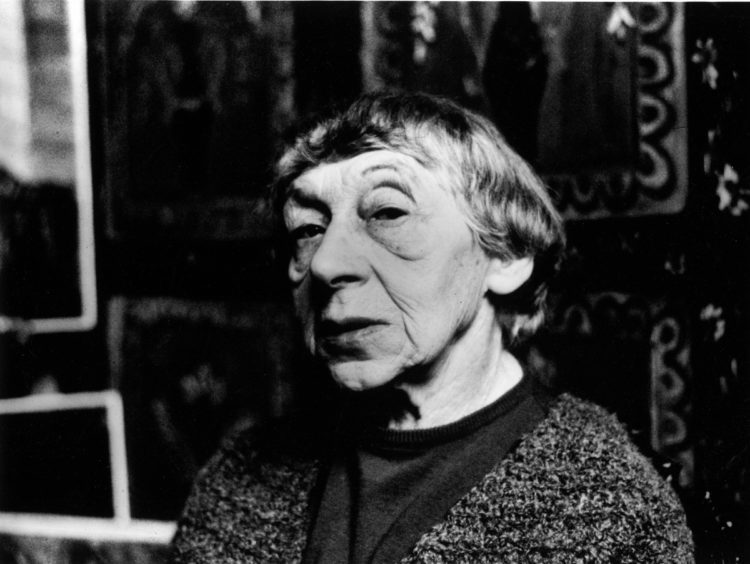

1897 — Germany | 1983 — Switzerland

Gunta Stölzl

1892 — 1976 | Germany

Benita Koch-Otte

1894 — Sweden | 1970 — Norway

Hannah Ryggen

1903 — Poland | 2000 — Germany

Gertrud Arndt

1930 — Croatia (before Yugoslavia) | 2022 — Italy

Jagoda Buić

1926 — 2011 | Spain

Aurèlia Muñoz

1944 | United States

Harmony Hammond

1889 — Iceland | 1966 — Denmark

Júlíana Sveinsdóttir

1964 | China

Qing Lu

1834 — 1910 | United States

Harriet Powers

1970 | Brazil

Lídia Lisboa

1964 | Argentina

Nicola Costantino

1908 — 2000 | Turkey

Hripsimeh Sarkissian

1960 | Argentina

Mónica Millán

1897 — 1978 | Mexico

Lola Cueto

1949 — United States | 2004 — Israel

Pamela Levy

1948 | Brazil

Sonia Gomes

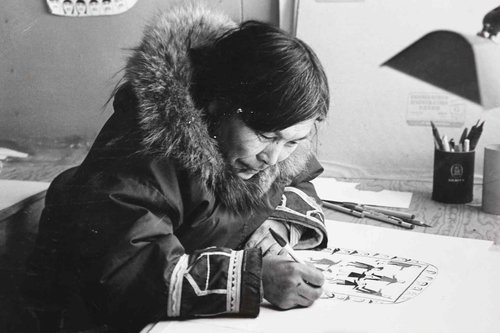

1906 — 1985 | Canada

Jessie Oonark

1928 — 2017 | France

Pierrette Bloch

1958 | France

Cécile Bart

1930 — 1998 | Canada

Joyce Wieland

1964 | Martinique, France

Valérie John

1968 | Haiti

Myrlande Constant

1970 | Mexico

Natividad Amador

1970 | United States

Teri Greeves

1967 | Uzbekistan

Dilyara Kaipova

1965 | Peru

Gaudencia Aquilina Yupari Quispe

1967 | United States

Marie Watt

1945 — 2025 | Norway

Elisabeth Astrup Haarr

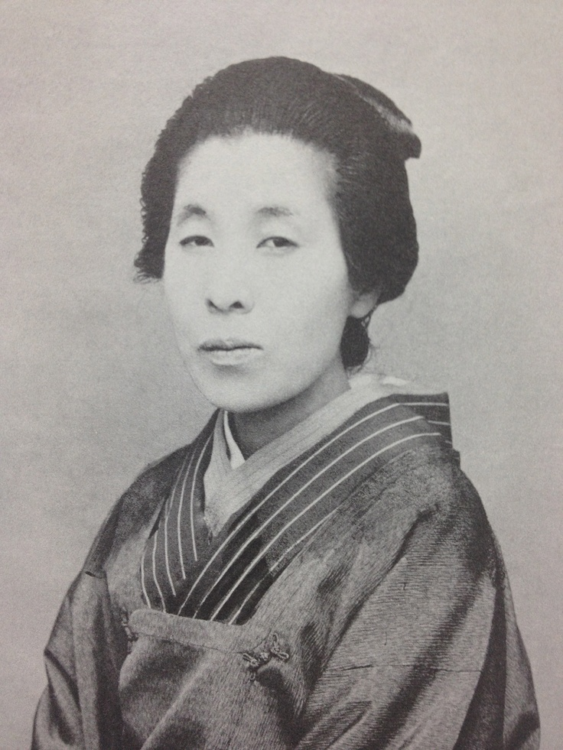

1875 — 1949 | Japan

Shōen Uemura

1957 | Argentina

Claudia del Río

1940 | Senegal

Younousse Seye

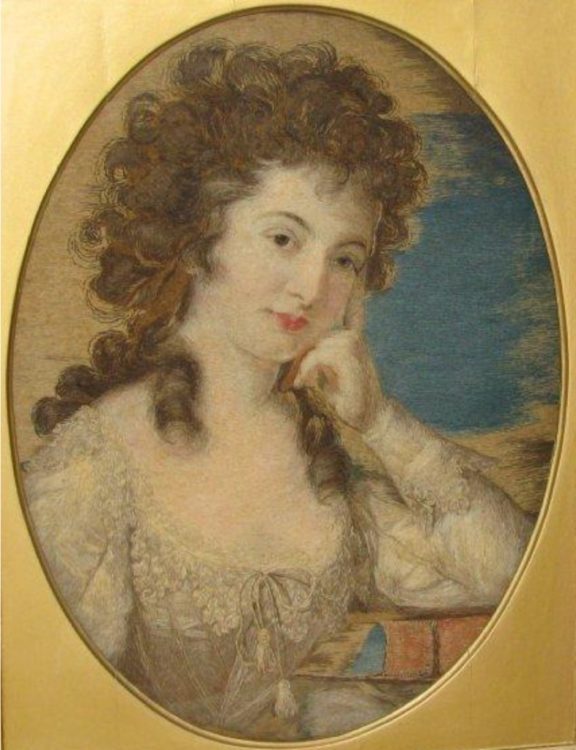

1755 — Great Britain | 1845 — United Kingdom

Mary Linwood

1966 | South Africa

Ntombephi « Induna » Ntobela

1965 — 2024 | Turkey

Gülçin Aksoy

1951 | Spain

Teresa Lanceta

1973 | Ukraine

Oksana Briukhovetska

1855 — 1931 | Norway

Frida Hansen

1908 — 2000 | Norway

Synnøve Anker Aurdal

1974 | France

Karina Bisch

1932 | Kenya

Rebeka Njau

1903 — 1993 | Norvège

Else Christie Kielland

1974 | Algeria

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar

1948 | United States

Joyce J. Scott

1961 | Palestine

Buthina Abu Milhem

1923 — Lithuania | 2019 — United States

Aleksandra Kasuba

1924 — 1966 | Japan

Saori Akutagawa (Madokoro)

1943 — 2014 | United States

Rosemary Mayer

1947 — 2023 | Malaysia

Fatimah Chik

1930 — 2023 | Indonesia

Siti Ruliyati

1965 — 1991 | Mexico

Elvira Palafox Herrán

1974 | Germany

Ulla von Brandenburg

1952 | Germany

Rosemarie Trockel

1872 — 1938 | Switzerland

Alice Bailly

1962 | Peru

Lastenia Canayo García (Pecón Quena)

1934 — 2023 | France

Marinette Cueco

1885 — Ukraine | 1979 — France

Sonia Delaunay

1924 — 2004 | Tunisia

Safia Farhat

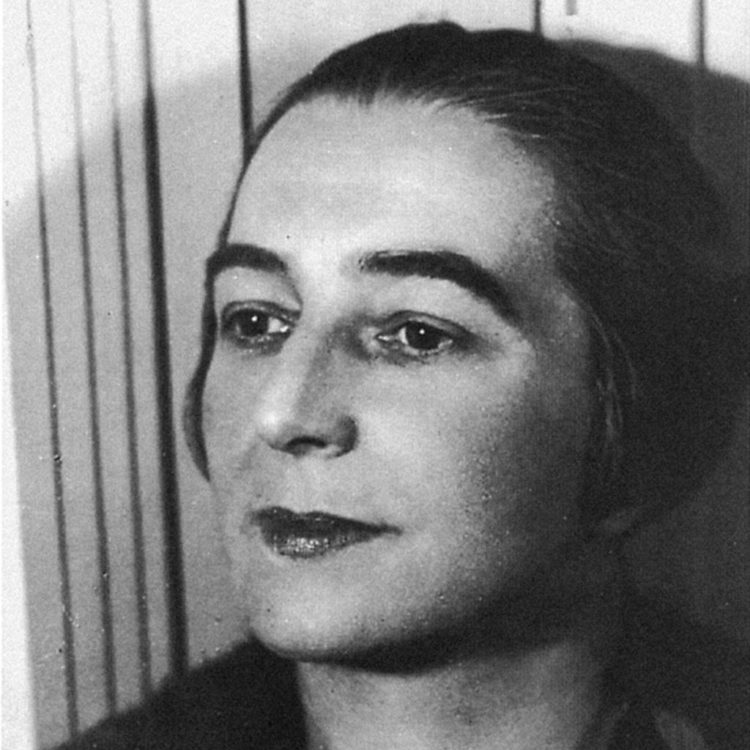

1890 — 1957 | Hungary

Noémi Ferenczy

1959 | Argentina

Mónica Giron

1957 | India

Sheela Gowda

1895 — Poland | 1975 — France

Alice Halicka

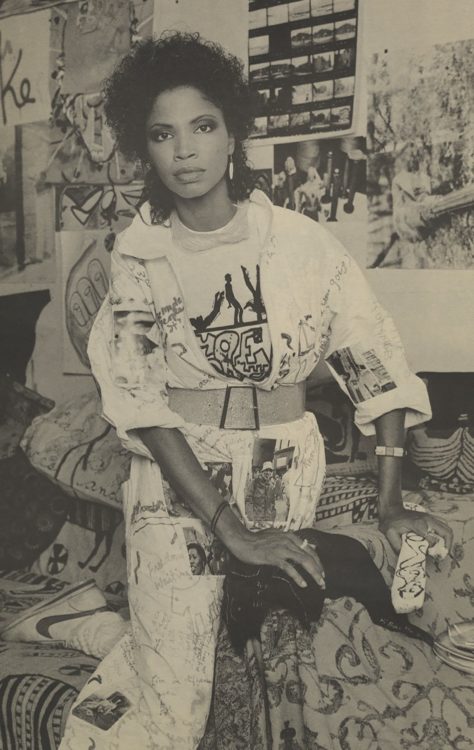

1945 | United States

Candace Hill-Montgomery

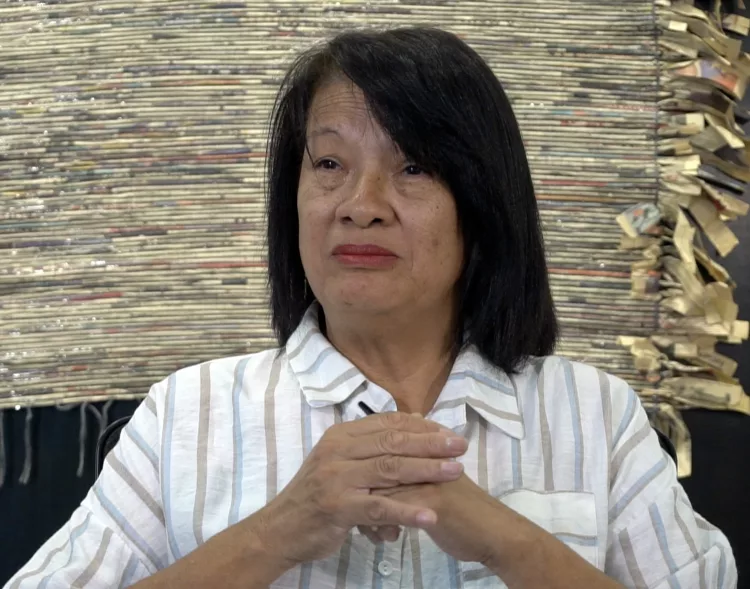

1971 | Malaysia

Yee I-Lann

1936 — 1997 | Nigeria

Josephine Ifueko Omigie

1889 — 1970 | Peru

Elena Izcue

1940 | Romania

Ana Lupaș

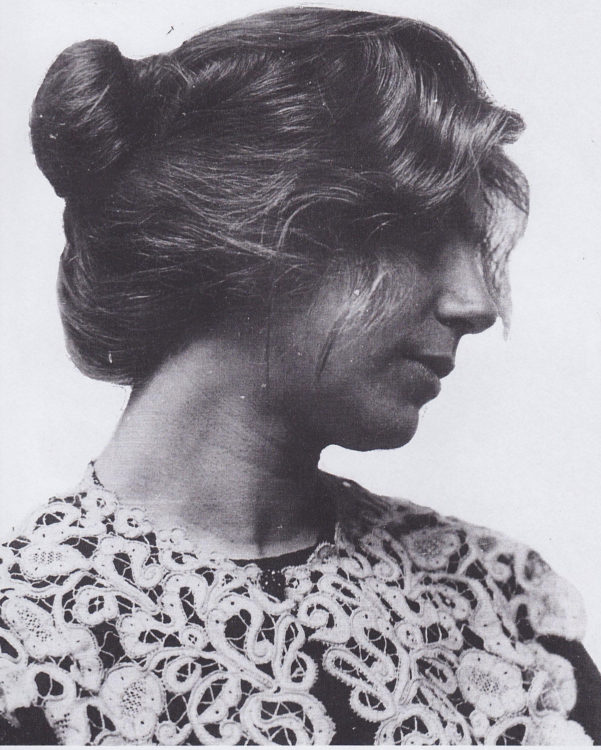

1949 — 2015 | India

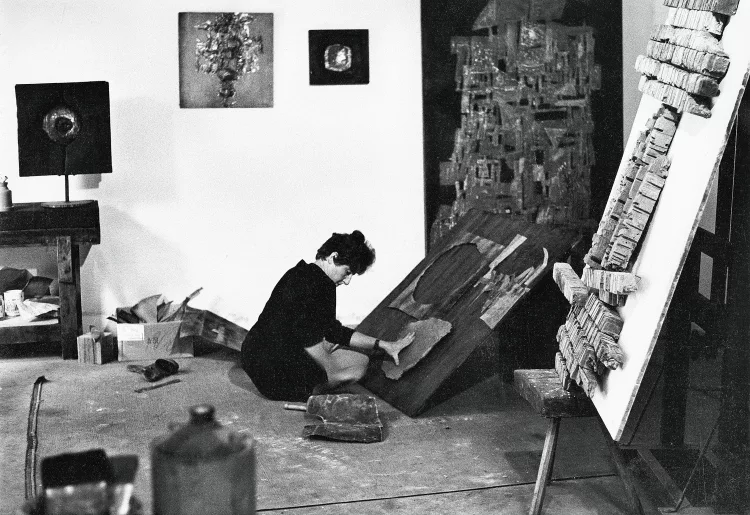

Mrinalini Mukherjee

1927 — 2004 | Brazil

Lygia Pape

1971 | United States

Shinique Smith

1953 — Poland | 2020 — France

Teresa Tyszkiewicz

1876 — 1959 | Netherlands

Adya Van Rees

? |

Céline Condorelli

1956 — 2020 | Madagascar

“Madame Zo” Zoarinivo Razakaratrimo

1971 | Uzbekistan

Anna Ivanova

1946 | United States

Nina Yankowitz

1974 | Guatemala

Sandra Monterroso

1847 — 1917 | Japan

Shohin Noguchi

1909 — Hungary | 1990 — France

Klára Spinner, dite Claire Vasarely

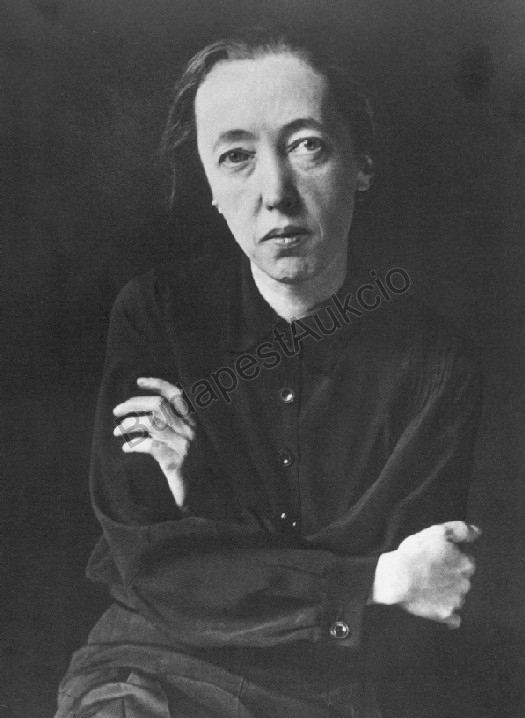

1919 — Kingdom of Hungary (Czech Republic) | 1994 — France

Vera Székely

1948 | Chile

Cecilia Vicuña

1974 | Chile

Loreto Millalén Iturriaga

1934 — 2014 | Colombia

Marlene Hoffmann

1965 | Cambodia